Once power is uncoupled from single actors and from intention, how do we understand its operation? Actors and resources remain key, but our focus here is on how these construct environments that determine power relations beyond their own, and restrict the feasibility of change. In the prison food episode of the podcast, Food Behind Bars chief executive Lucy Vincent explains how the Strangeways prison riot in the UK in 1990 caused a rethinking of prison design and allocation of space. The shape of the prison had enabled prisoners to take control of the kitchens and connecting corridors, vital resources in sustaining the protest and riot over many days. Communal space was a significant casualty of that change: Strangeways now is a space not only without food autonomy, but also without communal dining. This example provides a useful metaphor for the ways in which the structure of a space in which power acts can help determine the power dynamics within it. They may be conducive to some forms of power and not to others, and can restrain and liberate in different ways. A focus on patterns and dynamics does not remove responsibility, but emphasises that intention and other features of single agents may not be sufficient as either explanation or to allocate responsibility.

Regulation and economic structure

We might think of regulation as the application and removal of limits: for example, removing limits to whaling in the Faroe Islands or applying limits to polluting practices. While regulations may target specific activities, in combination they may establish power imbalances or draw boundaries around activities that only specific types of actor might cross. Jayson Lusk, for example, points to regulation of agricultural technology that means only ‘big players’ with sufficient funds and legal resources can navigate market entry, and notes how calls for regulation as a means to protect good practice against corporate control might have counterproductive effects. Co-founder of agri-tech company Sustainable Seaweed Sahil Shah, speaking in the event An open-ended discussion on power in the food system, points to the unevenness of global regulatory mechanisms, as an example of the disconnection between intention and impact. The agency of companies developing products and attempting innovation, of farmers wanting access to particular seeds and technology, is (re)directed and constrained by regulatory bodies and their geographical jurisdictions that mean resources and tools (and the power those bestow) go unfettered in some locations and restricted in others. Regulations never act in isolation, but in concert (intentionally or otherwise) with others. Professor in Global Development Philip McMichael uses the idea of ‘regimes’ to describe how diverse actors and regulatory structures might work in a matrix effect to define periods of history by the significance of relations of power, key acts and the regulatory environments they set in play. These regulatory tides come together in ways that enable or disable the flows and influence of different powers. From the colonial, British-centred ‘regime’ that first created the global food provisioning system, through to the ‘corporate food regime’ that was solidified with the creation of the WTO in 1995, McMichael shows how power structures and narrative norms impact not only sets of actors, but also the contexts of creation, innovation and governance in which they sit. Regulations are both a response to a situation and generative of new conditions: the ‘regime’ framing foregrounds the way that regulations have effects that outlive their existence on statute books. Education, culture and institutional norms develop around and in response to regulations, as well as creating the context for their creation, giving them temporally and spatially expansive effects.

Jennifer Clapp, whose recent research examines financial actors in the global food system and the politics of trade and food security, identifies three recent regulatory trends. She proposes that these - commodification, deregulation and financialisation - have shifted the make-up of actors in the food system and so changed the motivations and incentives at play within it. The degree to which these changes are the result of concerted effort by powerful actors, or actors working at significant removes from each other but with goals that happen to align, is not the focus here. Instead, the focus is on how the make-up of actors has changed the enabling and limiting factors in the environment, and so constricted the feasibility of change. In Clapp’s account of increasing commodification of agricultural products, technological changes in food production have foregrounded novel actors in the food space: 20th century developments in hybrid and, later, modified seeds, “gave rise to private corporations getting interested in the seed industry, because that need to keep producing seeds and hybrid seeds kind of built in intellectual property protection that made it profitable for corporations to get into the agricultural inputs sector.” Financial deregulation has also encouraged novel actors in speculation: food and agriculture were exempted from the original General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade of 1948, a treaty minimising international trade barriers to boost economic recovery following the Second World War. The World Trade Organisation, which absorbed the GATT in 1994, sought to liberalise food trade and the 1994 Agreement on Agriculture lifted the exemption. Regulation that previously functioned to ward against the price volatility in food markets associated with speculation has, according to Clapp, been eroded to make way for new financial products, developed at a remove from the actual commodities themselves - such as Commodity Index Funds and Exchange Traded Funds, that are indexes of share or commodity prices. Clapp describes the resulting financialisation as the increasing involvement of purely financial actors in food systems, at a level of resource and proportion previously unknown: “Corporations are increasingly being owned by these big asset management companies that are being driven by financial imperatives,” meaning those same imperatives become more involved in the food system. This in turn has encouraged mergers and acquisitions, resulting in growing consolidation. Patterns that enable and disadvantage certain activities, intentions or actors emerge from these regulatory combinations.

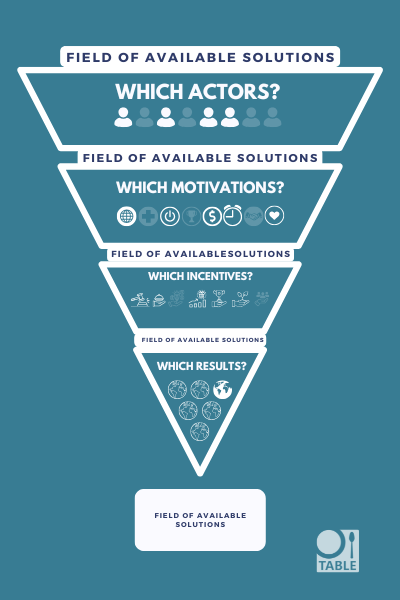

For Philip Howard, these patterns are not only a consequence but become determinant of what solutions and changes are available: “If you're a publicly traded firm, you're really going to be pushing the same model of highly processed foods, foods with a high profit margin, using very cheap ingredients, you're going to be pushing this cultural model of something that goes on the centre of the plate, rather than a more diverse and healthy diet.” The actors that contribute to this matrix restructuring are demonstrating another level of power: the power to determine the ranking of social priorities. Which actors → which motivations → which incentives → which results: this is the mechanism by which some contributors see the field of available solutions to current challenges - climate change, biodiversity, health and economic wellbeing - narrowing sharply.

Knowledge

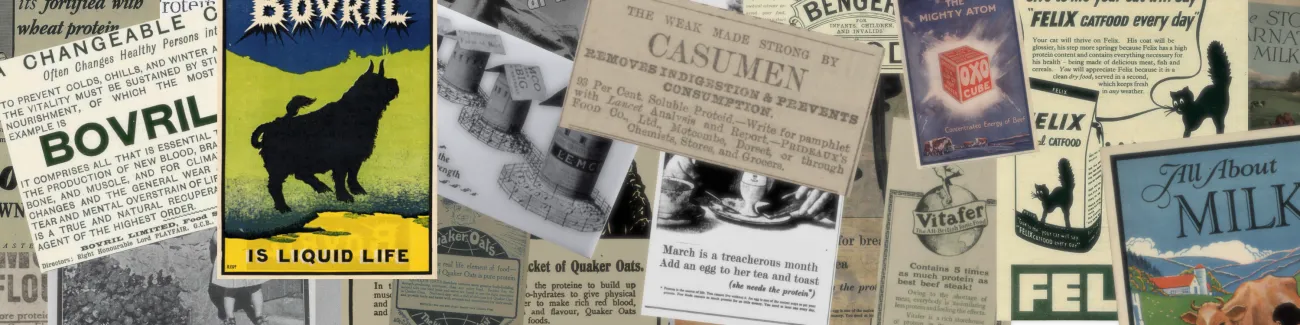

Knowledge develops in response to questions and hypotheses that may pre-empt and encourage particular findings. Tamsin Blaxter and Tara Garnett describe, in their cultural history of protein Primed for Power, how defining colonial malnutrition as ‘protein deficiency’ determined both research questions and directions during the ‘Protein Fiasco’ in the middle of the 20th century. This incentivised a flawed narrative identifying protein deficiency as the biggest world health issue, alongside predicted population growth as an assurance of huge protein demand. Protein deficiency was convenient:

“The realisation that malnutrition was a particular issue in the colonies created a political incentive for colonial powers to find a diagnosis that was not poverty or a simple lack of food: whereas impoverishment would seem to imply colonial maladministration, if the explanation was something specific to the cultures of colonised populations then colonial governance could not be to blame.”

The framing of the Kwashiorkor (a disease initially understood as a protein deficiency) problem as part of a culturally-informed protein deficiency demanded a nutrient-specific, rather than systemic, response. The sunk costs fallacy provided a psychological driver, alongside financial incentives like research opportunities and institutional support, for researchers to disregard contradictory evidence. Problems can be tuned to accept responses that rely on particular forms of knowledge. Earlier in the century, war economies had similarly encouraged a technical response – “blockades and rationing created a need to determine the minimum diets that could keep populations healthy,” as well as to determine how much protein the agricultural sector should produce. This focus changed the health and nutrition goals of a generation of scientists, leading to “greater power in the hands of nutritional scientists and a reification of nutritional science in the context of concrete goals.”

This set of contributors wants us to be wary of congeniality between knowledge types and particular action agendas, as an indicator of power influencing evidence. Both the generation of knowledge and its deployment are strategic as well as responsive. Rebecca Sanders notes that purpose has a role in determining what knowledge is made available: during her training as a farm vet, she highlights the understanding implicit in teaching was that the level of care allocated to an animal was determined by its ‘use’ – domestic or livestock. The goal in question - companionship or food - determines what knowledge is necessary and is acquired. Which knowledge types are prioritised is significant because they may lead to specific solutions. Philip McMichael recognises the value of landscape data sets collected and elaborated on a global scale, but is wary of how ownership might affect their deployment. Such datasets may support precision agriculture and the achievement of net reductions in emissions or fertiliser use, yet, “it's not addressing the issue of who has access to the land, who has knowledge.” The knowledge – if owned and controlled by digital corporations with no local connection - predetermines what is proposed as a viable solution: “we're talking about monocultures. We're not talking about biodiversity or polyculture,” technical innovation over social change.

What counts as knowledge, what sits in the pool of material that forms the references and justifications for a society, is not only determined by whose knowledge it is. For Francisco Rosado-May and Hassan Roba, contributors to a GAFF report on evidence bases for regenerative farm practices and speaking in the Whose knowledge counts? event, what counts is also determined by a collective activity of validation. Roba and Rosado-May are at pains to distinguish the sources of recent, newly introduced knowledge to their indigenous communities, and the mechanisms by which their communities became less familiar with their traditional knowledge base, accumulated across generations. In Roba’s account, children of indigenous communities were taught in government schools, and taught agricultural practices that contradicted their traditional methods. Instilled in them too was a hierarchy in which that new knowledge was defined as progressive and productive, with their indigenous knowledge seen as backward and lesser. This was part of a process of validation of the new knowledge forms, a process facilitated by those actors with power. What knowledge accumulates to people, communities and cultures over time is not an inevitable or natural process but directed, even manipulated, by power dynamics.

This validation process also happens via theorisation – i.e. an explanation that can structure facts under hypotheses. Logical flaws, and their ethical implications, are made visible by theory. Considering the connection between human-animal and human-human violence suggested by studies on meat processing plants, Sanders notes the absence of a theory – a story of cause and effect - expressing this connection: “The authors conclude these ‘social problems and phenomena … [will remain] undertheorised unless explicit attention is paid to the social role of nonhuman animals’.” Inattention to particular parts of the food system is reinforced as long as the contributing knowledges remain isolated. While knowledge remains disparate, rather than cohered in explanatory narratives (theorised), it struggles to connect to other ideas and disciplines, or to take a role in stories of cause and effect. As such, absence of theory is an absence of tools for narrative construction, and the untheorised knowledge is more easily constructed out. In both cases, it’s not about presence and absence of information, but what is foreground and background, and so available to learning or interpretation.

Narrative and language: contested terrain

Narratives – like theories - attribute an order and an arc to collections of events, actors and outcomes. They are an inevitably incomplete account of all the facts by dint of the addition of rationale and a clarity of cause and effect: some events will fit better, so some are brought into prominence and importance whereas others, no less real or established, fade or lose attention, and are not repeated in the retelling. As such narratives both claim and consolidate power. Tamsin Blaxter recounts the persistence of the narrative of protein deficiency long after the collapse of its founding evidence:

“all of the cognitive and cultural biases favouring protein and meat were still there…Scientific claims can leave a cultural imprint which lasts long after expert consensus has moved on.”

Narratives continue to hold sway beyond the dismantling of their components, and in this is their determinant function. They serve not only to describe the past, but to inform - even prescribe - the future by positioning the present in an arc.

The validating role of cohesive theory is illustrated in how theory might leap ahead of a knowledge base, or long outlast it. Researcher Jeremy Brice describes the ubiquity of the nutrition transition theory and its morphing into a narrative of inevitability rather than warning or precedent. The investors he interviews work in a range of structures from international development grants to venture capitalism; their focus is Sub-Saharan Africa, but most work on a global scale and are not based there. All Brice’s interviewees cite the necessity of increased protein production in response to a predicted increase in demand in the region – a prediction based, at least in its proportions and its isolation of protein from a wider increase in demand for nutritious food, in the past and in different geographical regions: “nutritional transition models seem to have kind of transformed from being a description of past economic and dietary changes in other parts of the world into really almost a predetermined pathway.” As the prediction informs and directs investment, it becomes self-fulfilling. The model is congenial to narratives of both profit and development, and so persists. Narrative power appears for Brice as the capacity to produce an authoritative vision for the future and spark action as a result. The excess of that power is an ability to escape, by its aesthetic durability, the constraints of both intention and evidence.

These examples alert us to how we process narrative: we do not evaluate purely by accordance with evidence or external reality, but appreciate coherence and put greater confidence in stories that hang together well. It’s why knowledge as part of a theory is stickier, more available to connection, than knowledge in isolation. Accepting the role of narrative gives language a significant role in signalling and embedding narrative authority. Politico journalist Eddie Wax flags that the French Agriculture Minister has been increasingly using the term ‘food sovereignty’, and the whole government is beginning to take it up. Wax notes that this is a very different version of food sovereignty to that espoused elsewhere in civil society, for example by international peasant movement La Via Campesina. Words are indicators of possession of some body of knowledge, but not proof of its mastery nor its use. Shefali Sharma draws on IATP analysis:

“A lot of these companies are shifting their narratives, and actually co-opting a lot of civil society narratives around regenerative agriculture or the terms around agroecology.”

By using the terms, they can insert themselves into narratives created elsewhere, and so claim a role in that narrative’s end goals.

While the story holds, it can be appropriated for new interests. Language can be co-opted from the communities in which it has evolved, allowing words to be stripped of central meanings for the convenience of different speakers. Single words are in this way contested terrains in themselves, and power dynamics determine authority. Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquin strongly resists attempts to define Regenerative Agriculture, “Defining something like this is one of the most purely colonising things we can do… after you define it and appropriate it, then you structure systems to protect and then expropriate it and invalidate anybody who claims otherwise.” Definition here is not descriptive but prescriptive; it doesn’t only delineate the boundaries of a term, it makes a claim for future decision-making power. Giuliana Furci makes a more positive case for the power of language, describing her campaign as part of the Fungi Foundation to recognise fungi as a protected species under Chilean law – the only nation to include fungi in legislation. As a result, international organisations began to include fungi in their own language: “language creates reality and by acknowledging the interconnectors of nature in language, from a top-down approach, you're ultimately triggering obligatory change.”

Imagination and incumbency

There are two reasons why structure and dynamics are significant for our contributors. First, incumbent - existing, established - ideas gain a power and advantage simply by that establishment. Second, if power structures shape relationships between actors, they also ‘structure’ how solutions are imagined. Imagination and innovation are for many contributors the first victims of power dynamics which it is harder to be outside than within.

For several contributors, the reason for stasis – absence of change or challenge to power dynamics - is familiarity with, and the familiarity of, the current system. Accepted, past and ‘normal’ ways of doing things hold an incumbent position that is to a degree their own justification. Jason Clay, reflecting on efficiencies he introduced to an agricultural supply chain, suggests: “Sometimes it's not power, per se, sometimes it's just inertia, and inefficiencies that have been ignored for so long that they seem to be the norm.” For Sahil Shah, the structure that results from the pattern of regulation across and between countries is not a necessarily strategic or conscious creation: “huge amounts of power sit with the regulatory institutions that determine which activities can and cannot take place and often these aren’t necessarily based on what’s optimal either from a market or an environmental standpoint, but often due to what has happened before, and what is socially acceptable.” What has happened before sets the terms of what is thinkable now. Interestingly, neither Clay nor Shah identifies these norms as operations of intentional power. In Jennifer Clapp’s reflections on diversity of actors within a system, there is no ‘bad actor’ holding responsibility, simply that while we privilege one kind of system we inevitably limit the space for alternatives -

“a globalised and concentrated food system does tend to take up space that could be occupied by local and alternative and diverse food systems.”

For those contributors interested in exertions of power via norms and social machinery, this inertia is not an absence of agency, rather an inability to identify that agency by its alignment with intention; the responsibility to dismantle the energy reinforcing those norms remains.

Imagination, or as Julie Guthman puts it, “the cultural power of what we believe is possible,” is, as a result of this incumbent machinery, constrained from acting in the service of alternative ideas. Tara Garnett asks in the What is Ecomodernism event if technological and growth models of globalisation take up oxygen from alternative ideas. The protein challenge highlighted by Tamsin Blaxter in the kwashiorkor moment and protein fiasco, led to by a colonial cultural history of protein in relation to race and culture, and magnetically convenient in its suggestion that a global ill could be ‘fixed’ by the provision of sufficient protein products, was a mould - a challenge set in certain terms - that demanded a specific set of responses, and the solutions fit the mould rather than the problem. Clapp describes the reinforcement of a financialised and disproportionately corporate food system as a limit to innovation. On arguments about innovation from corporations, “It's only one kind of innovation, and it's crowding out those kind of innovations that are more ecologically grounded.”

The corollary of a focus on the power embedded in and distributed by dynamics that limit alternatives is, across much of the material, a sense of frustration. For Busiso Moyo, those South African citizens not well supported by the current arrangement of power relations are already living in a different system which is hermetically separate from a more mainstream version: “We have a highly efficient, commercialised farming agriculture sector. And then we also have this food system that is anchored in rurality and peasant farming… there are those who experience the food system in South Africa in the same manner that someone in a first world country would experience the food system, and then there's those who experience the food system in a manner that someone in a warzone probably would have to interact with the food system.” For Julie Guthman, alternative food system patterns are available under certain restrictive conditions but not as a choice embedded in current structures: “some who have the means or knowledge or wherewithal [can] opt out of the industrial food system, but they haven't really threatened the industrial food system.” Alternatives happen in the margins, and represent an abdication rather than a real choice. A more hopeful view comes from Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquin and takes us back to food, at least as a metaphor:

“The one we feed is the one that wins.”

This metaphor makes room for the more evasive forms of power – such as narrative - alongside the tangible, that might be ‘fed’, i.e. nourished, with words and attention as well as money and resource.

Comments (0)