What scale for the food system? Moving beyond polarised debates

Through a series of dialogues and discussions with food systems stakeholders throughout 2021, TABLE explored the theme of ‘scale’ in the food system. Our key activities include:

- Report: summarizes the key areas of agreement and contention about scale in the food system

- TABLE launch event: including a conversation between Charles Godfray (Oxford Martin School) and Pat Mooney (ETC group) on how localised or globalised the food system should be and reflections from the TABLE community

- Podcast series: 14 conversations on scale, a recap episode summarizing our findings and an episode where Pat Mooney and Charles Godfray debate the future of food systems.

Scroll down to the bottom of the page for more information on the key findings.

Project background

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the attention to the scale at which livestock and other agricultural products are produced and shipped around the world. Though the goals of reducing hunger, mitigating the impacts of climate change, and building a fair food system future for all are shared by most people, the appropriate scale at which the food system should function – for example whether nations should increase food self-sufficiency or increase international trade, or if small- or large-scale agriculture is to be preferred, remains deeply contested.

The debate on scale in the food system extends beyond spatial considerations. “Scale” can also be applied to temporal, moral and cultural issues. For example, what are the benefits and drawbacks of making food policy over different timeframes – weeks, years, centuries? Do – and should – people care as much about their local communities, economies and ecosystems compared with distant ones that they are not directly embedded in? What does “local” economy even mean in the age of globalised supply chains? How do people decide how far to extend their “moral circle” – should they care about the wellbeing of individual cattle, chickens, fish, shellfish, insects or plants? How closely do people identify with the “traditional” diets of their local areas?

While there are certainly strong differences in opinion, attention is often focused on the most extreme arguments within the debate, glossing over a broad and rich spectrum of moderate, nuanced and regional views that do not always fall into simplistic “localist” vs. “globalist” positions.

This project aims to take a closer look at the arguments, values and assumptions that underpin debates around globalisation and localisation in the food system, doing so through the involvement of a wide range of food systems stakeholders in a process of interviews, dialogue and discussion.

Interviews and Blogs

Background explainers

Key findings

Areas of agreement: key messages shared by our speakers

- Assumptions need to be challenged: Key terms such as ‘smallholder’ encompass multiple realities, and assumptions about food systems (e.g. that small farms have lower yields; local food systems are more democratic) may not be correct or may be locally specific.

- The local-global binary is unhelpful: Food systems encompass multiple, interconnected scales. Therefore, problems found in one place may be resolved elsewhere, or by processes seemingly unrelated to food systems outcomes.

- Diversity of scales is essential: There is no single ‘ideal’ scale for the food system; it is important to maintain a diversity of scales and ensure that they harmonise rather than compete. Currently, the large-scale or global (e.g. transnational agribusiness; global trade; large farms) tends to dominate, and displace or overwhelm alternative scales of action.

- The state plays a key role: National governments need to play a key role in food systems, in order to encourage sustainable farming practices, to improve the resilience of food systems, and to ensure that markets and the private sector contribute to food security, equity and sustainability.

Areas of contention

Each speaker offered nuanced reflections, and no one advanced the more extreme stances common in polarised debates. Nonetheless, certain topics proved more divisive, in particular, the future of smallholder farming, the benefits of global trade and the governance of food systems.

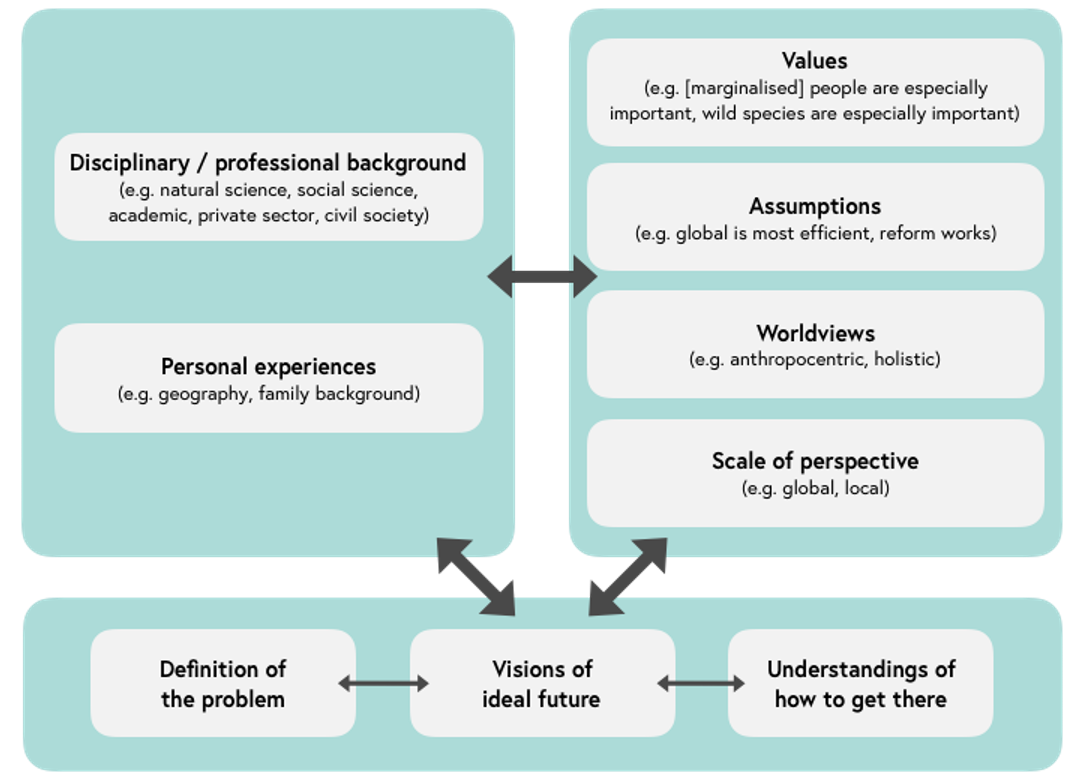

What factors influence opinions on contentious topics?

- Perceptions of reform: Some speakers were optimistic about the possibility of generating reform within the system, whereas others were more sceptical and promoted alternatives to dominant scales of activity.

- Different values and priorities: All speakers highlighted the importance of food security, sustainability, social equity and resilience; however, speakers prioritised and understood these goals differently, and disagreed on the scope and pace of change, and the specific interventions deemed necessary.

- Disciplinary and professional background: Speakers’ disciplinary or professional background seemed to affect their interpretation of history, the scale of focus they adopted when considering food systems change, and, in turn, their opinions on contentious topics.

- Personal experiences: shaped speakers’ aesthetic preferences and expectations for global interactions.

Figure 1. Factors influencing people's vision of the figure