As I went through the process of extricating myself from an abusive relationship, back when I worked as a meat-vet, I started recognising my life was saturated in violence. That experience changed my perspective on not just my personal life, but the meat industry, the veterinary profession (my profession!), and our society at large. It forced me to rethink and re-evaluate some of my core-beliefs and values, and led me to make some fairly substantial changes in how I move through life.

Content note: this piece mentions domestic violence, genocide, suicide and animal slaughter.

About the author: TABLE intern Rebecca Sanders graduated as a veterinarian in 2011. After six years as a meat industry veterinarian in New Zealand, her growing concerns about the ethical and environmental implications of the meat industry prompted a radical change in trajectory and transition towards sustainable agricultural research.

Part One - Waking Up to Violence

Farming

What was I thinking? Isn’t that the age-old question when we peer back through the distorted lens of years at our younger selves?

It’s uncomfortable now to recall the frenetic force-filled striving of my twenties - the emotional context out of which all my decisions then arose.

I was an animal-obsessed kid. Brainy but naive, I left high school wanting to work with animals, and found ways to make this happen. I worked with horses, and gradually found my way into farming. I learned everything I could, soaking up knowledge, tradition and lore from the farmers and farmworkers I met and admired. Updating my value system in respect to animals as fast as I updated my knowledge-base, I internalised the prevailing attitudes of farmers towards their livestock. These creatures were property: kept for profit. No farmer wants his animals to suffer or die - it’s bad for business. My childlike love for the animals morphed into a love of the lifestyle they allowed me to inhabit. I travelled, worked as a cowgirl in the Australian outback, attended rodeos, shot kangaroos, rode horses, branded cattle and mulesed sheep. It was barbaric, earthy, feral and glorious.

It was also an arena in which I was always going to be an outsider: young, female, foreign, and most-damning-of-all, a city-kid. When my Australian visa expired, I resolved to return home to the UK to study veterinary medicine, dreaming this would be a better-paid, higher-status extension of my farm-hand days.

Vet School

Vet school was a culture shock. My peers were younger than me, 95% female, and for the most part supremely uninterested in farming and food-production systems. We learned anatomy and physiology, husbandry and epidemiology; we studied pathology and navigated parasitology. During all these classes, the unspoken subtext was always “and this relates to what the animal’s owner requires of their animal”. The function of a companion animal is very different to that of a production animal - this, far more than species, dictates what sort of care that animal receives.

Imagine for a moment having a pet cow. You don’t milk her, and you have no intention of eating her. This animal is your loving and bonded companion. She lives in your house; you go for walks together; you play chase together in the park. Your mum always gives her way too many cow-snacks whenever she comes to visit. The sort of veterinary care you’re going to want for your pet cow if she breaks a bone is far more akin to that which you might want for a pet dog than to that which a farmer might want for a dairy cow. In veterinary medicine, it is function, not species alone, that determines how we approach treatment.

Image: PublicDomainPictures, Cow, Pexels, Pexels Licence

Formal lectures on ethics were a compulsory part of my veterinary training. In these I learnt the names of different ethical approaches to animals: utilitarianism, animal rights, deontology. The focus - as I recall - was always the duties and responsibilities that we owe the individual animals, (or in the case of livestock, a specific group of animals) “under our care” as the veterinary oath makes clear. Graduating as I did in 2011, I recall no mention made in these, or any of my other classes, of the role of animal agriculture as a driver of climate change and biodiversity loss. Animal agriculture plays a significant role in driving land-use change, in greenhouse gas emissions, in the eutrophication of watercourses and in the consumption of fresh water 1 ,2. Ninety-six percent of mammalian biomass across the whole planet now consists of humans and our domesticated species 3. In the years since I graduated, I’ve come to regard the omission of these topics from the veterinary sphere of concern during my training as ethically problematic 4. Maybe if I went to ethics classes, and managed not to have my mind opened in any way, the fault is with me. I do wonder though if the content and delivery mightn’t have been unconsciously biassed to support the status quo. My suspicion is that these classes ultimately served as yet another rationalisation tool, reinforcing the "everyday ethics" I and my peers were imbibing as we became conditioned to the socially accepted norms of vet practice, pet ownership and agriculture - all arenas in which the objectification, commodification and exploitation of animals is socially normalised.

To justify this commodification of animals, I leaned heavily (as I suspect many in my profession and the agricultural industry do) on utilitarian ethical models. Utilitarianism posits that the “right” courses of actions are those that engender the greatest good, for the greatest number. If we chose to interpret this as meaning “the greatest number of humans” exclusively, if we discount the fact that utilitarianism is in no way an inherently anthropocentric philosophy, and if we ignore the substantial human cost of the environmental degradation that is caused by animal agriculture, it becomes possible to use this philosophical model to legitimise the ways we treat farmed species kept for food production. The payoff in terms of food makes the welfare costs incurred by farm animal species palatable - literally.

Meat Industry

On graduating, I was fortunate to secure employment in New Zealand working for the government ministry that enforces food-safety and animal welfare legislation in the meat industry. Working as a meat vet, I came to suspect there was a mismatch between the general public’s (totally valid and well-placed!) concern for animal welfare issues in these systems, and the issues that as a vet I felt were impacting the animals in my care the most. For context, I worked with sheep, beef-cattle, cull dairy-cattle 5, cull-calves from the dairy industry, farmed deer and wild-caught goats - all (with the exception of the 4-day old dairy cull-calves) animals raised on idyllic-looking pastureland. Extensively raised grass-fed ruminants on well-managed farms tend to live lives that for the most part allow them to perform a range of evolved behaviours compatible with good welfare 6, whilst the farmer has a vested interest in keeping them well-fed and healthy to maximise production. The extensive New Zealand pasture-rearing conditions for ruminants are in stark contrast to the intensive shed systems for rearing pigs and broiler chickens, and the American systems of fattening beef cattle in feed-lots. These might be described as “grain-fed” systems, where instead of the animals grazing at pasture or foraging for food, they can be kept confined, and high-energy food delivered in-situ. Compared with the (similarly sized) UK, New Zealand isn’t a big cereal-growing or importing nation 7. The export market for grass-fed red-meat, however, is one of the major pillars of the NZ economy.

As welfare officer (amongst other things), my “ante-mortem” 8 inspection of the live animals included an assessment of the welfare of each group of animals. This inspection of incoming livestock was inevitably the place I’d discover the most welfare issues. Occasionally welfare issues that arose at the slaughter premises themselves would be identified (and rectified) - for instance if an animal broke a leg whilst being unloaded from the stock truck - but my impression was always that the majority of issues were those relating to on-farm conditions and transport. Ultimately, once the animals arrive at the abattoir, they’re very quickly killed, and once they’re dead, they’re no longer able to experience any harm. I’ve seen footage of slaughtered animals being effectively stunned and subsequently processed that was being hailed as cruelty. There’s a logical fallacy to that argument - it’s impossible to be cruel to something that’s already dead. Whatever suffering the animal incurs has to occur prior to that point.

Thus the majority of welfare conditions I recognised related to farming practices and transport. To me, transport always seemed to be the issue that receives the least public attention. For a fit and healthy animal, transport is probably far and away the most inherently stressful part of the whole slaughter process, and it’s one that every animal sent for slaughter undergoes - including wild-captured animals that are rounded up and transported to slaughter premises 9. As a government official, my role in the process was to ensure the legal minimum welfare (and food safety) standards were maintained.

New Zealand animal welfare legislation is mandated by the Animal Welfare Act 1999, under which various codes of practice, including one covering transport 10 , have been issued. This code stipulates minimum standards for (among other things) how long different classes of animals are legally allowed to be held off food or water, how long they can be transported before getting a rest, training and competency of stockmen, transporter design, requirements of loading and unloading facilities, and much more. These were the “rules” I had the power to enforce. For the most part they were effective in that the animals that were transported within the legally acceptable framework were able to withstand their journeys and reach their destination intact. The processes of yarding and penning animals on the farm, of holding them off feed prior to loading them onto a truck, transporting them, unloading them into holding-yards at the slaughter premises, where they’d often wait overnight to be killed - it always struck me that this part of the process was less graphically confronting that visuals of slaughter itself, but was probably the most stressful part of the entire process for the animals themselves. Nonetheless, I was proud to work as a government official, upholding the standards of an industry that was so significant to the NZ economy. Working in a role that ensured animal welfare standards were maintained, and the food that was produced was safe for consumers felt important and worthwhile. Nowadays, I regard that entire six-year period of my life as “propping up the status quo”. I got paid a decent salary and had a nice life, but my entire livelihood was contingent on the deaths of thousands of other sentient creatures. Nevertheless, I might still be there, if it weren’t for a series of paradigm-shifting events that occurred in my personal life, which altered my perspective on just about everything.

Domestic Violence

I embarked on a relationship with a New Zealander. Some of his behaviours, evident from the outset and which I now regard as relationship red-flags, escalated. Eventually, I found myself battered, bruised, and in the back of a police car being driven by a pair of burly, pig-hunting cops. I vaguely recall the cognitive dissonance of listening to this hyper-masculine pair, calmly chatting about their latest gory hunting escapades whilst I sat in the backseat, reeling in shock at both my ex’s calculating brutality and my own feral retaliation.

This is a difficult story to tell. It’s hard to recount objectively events that are still loaded with emotion. It’s harder still to convey the impact of my constant mental “replaying” of traumatic events - scrutinising triggering memories through different “lenses” in an attempt to decode what happened and understand why. The purpose of this recounting is to share the insights I gleaned from a formative (if inescapably traumatic) episode. The struggle to make sense of my situation, to rehabilitate from the abuse that had been entirely invisible to me even as it dominated my life was perhaps the hardest process I’ve ever undertaken. Embarking on this journey, this process of self-examination (and eventually social critique!), was not something I’d have committed to willingly: I did it only because I felt I had to. I could see no other way forward.

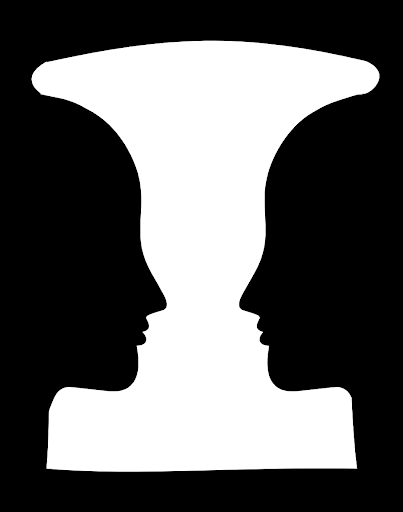

I attended therapy, counselling, a well-intentioned (but methodologically suspect) “end-to-violence” intervention. I read extensively about gender-violence and the mechanisms of controlling relationships. As I became intimate with the dynamics depicted by the Duluth Wheel 11, and the Cycle of Violence 12, 13 I began recognising their patterns everywhere. It was disconcertingly akin to seeing patterns emerging from a Magic Eye painting, or looking at the Rubin's Vase image (below), and finding one’s visual construct shifting back and forth between the two interpretations of the image. The image doesn’t change; what changes is our construction of meaning from the images. Once I had begun to recognise the patterns of violence, they became visible wherever I looked: in the fairytales I’d been told as a kid, in the overly-gendered caricatures that pass for representations of men and women in the media, in the dynamics of so many of my friends’ intimate relationships, and in the low-level, constant “everyday sexism” 14 to which women and girls are relentlessly subjected.

Image: Rubin’s goblet profile, Free SVG, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

I maybe didn’t realise it as such, but I was scrutinising the roles that both overt and covert violence played in every aspect of my life. How had I been so blind to the subtle violences inflicted on me? How had my denial made the patterns of abuse so invisible? I began to notice the myriad ways in which I inflicted micro-violences on myself. Working too hard, exercising when I was exhausted, pushing myself ever harder and harder. My body was in constant “fight or flight” mode. Sleep-deprived and exhausted, I had no way to distinguish between anxiety, physical exhaustion, or the effects of the caffeine I depended on to keep moving. The distinction between the harms I did to myself and the harms I’d allowed another to do to me began to blur, until eventually I saw all these things as symptomatic of the same overall thing: I’d been acclimatised from infancy to a world saturated with violence.

In search of meaning

It was during this period that I first read Man’s search for Meaning - Viktor Frankl’s simultaneously chilling and inspirational account of his experience of state-sanctioned violence in various Nazi concentration camps during the Second World War. One memorable evening I read about the experience of Jewish people arriving at Auschwitz on cattle-trucks, being assessed as they disembarked by a Nazi guard (I envisioned him as a bureaucratic type, with a clipboard, and a stamp), and being assigned to one of two queues, one of which was for those inmates sent to the labour camps, the other for the new arrivals assigned straight away to the infamous “showers”. The following morning I was in the stockyards at the abattoir, with my clipboard and official stamp, inspecting sheep as they arrived, and assigning them to their various outcomes. I caught myself wondering - what did that guard think about his job? Was he, too, diligent and hardworking - fundamentally conscientious and wanting to do his job to the best of his abilities? Did he go home to his wife in the evenings, worrying he might have somehow done his job suboptimally? Thinking these things, looking over the sheep, I had this disconcerting realisation that I didn’t have any rationale that could justify what I was doing, any more than that Nazi guard did. Once I’d made that mental leap, once my paradigm had shifted to that degree, I couldn’t draw any logical distinction between the horrific violence Viktor Frankl had endured, and the industrialised slaughter I oversaw on a daily basis.

I am well aware that drawing comparisons between the Holocaust and animal slaughter is seen by many as morally problematic and dehumanising, and runs the risk of being triggering and insensitive to Holocaust survivors and their descendants. By writing the above I doubtless run the risk of exposing myself to criticism and censure. Worse still, I run the risk of further harming those already injured by these events and by a continuing legacy of anti-Semitism. I have no wish to trivialise the atrocities perpetrated upon the Jewish peoples by this genocide, or to in any way contribute to the ongoing harm caused by Holocaust denial or minimisation. The fact remains however that this is the thought process that unfolded for me whilst I was working in industrialised slaughter. Reading and reflecting upon Man’s Search for Meaning was profoundly instrumental in shifting my thinking about, and approach to, morality-based decision-making. It would feel deeply dishonest to omit such an important experience from this recounting 15.

Yoga

It was also around this time that a buddy took me to my first yoga class. After ninety-minutes of dyspraxic struggling and copious sweat in the sauna-like heat of the studio, I lay down for the end-of-class relaxation. For a short moment the cacophony of my incessant internal dialogue calmed. My exhausted body relaxed. My racing thoughts slowed. I had a glimpse of what internal peace might feel like. What I experienced first hand is increasingly being backed up by clinical research, with mounting evidence pointing to the value of yoga in managing stress, anxiety and depression 16 , 17, 18.

It wasn’t until a while later that I first came across the Sanskrit word ahimsa meaning “non-violence”. By the time I learnt there was a specific word for this concept I was already starting to use yoga to examine the ways I’d habitually “force” myself to do things. It seems ludicrous with hindsight that anyone would ever use emotional brute-force in an attempt to “make” themselves relax. But as the saying goes: “if all you’ve got is a hammer, everything is a nail”. Through yoga I started to experience directly how damaging this goal-focused approach can be. When I was gentler, and let go of forcing, I was more able to gain something worthwhile from the practice. Often, this wasn’t the exact pose that I was ostensibly trying to create, but something far more subtle - for instance finding a way of approaching the challenge that was kinder, gentler and ultimately more compassionate than how I might hitherto have approached it.

A dissolving rationale

Until this point, I’d rationalised slaughter as unpleasant but necessary: food is, after all, essential. This argument only holds however if animal products really are as essential to our diet as I’d hitherto blindly accepted. I began to question this neccesity.

I was certainly aware that not just the absolute quantity, but also the relative proportions of animal products in diets across much of the world have been increasing steadily over the last few decades 19,20, and furthermore, that overconsumption of meat in western diets is associated with health issues such as heart disease, bowel cancer and diabetes 21. Similarly, I was aware that dairy products are, historically speaking, still a relatively “novel” food source in many parts of the world. The ability to digest the milk-sugar lactose in adulthood results from a genetic mutation that’s mainly present in people from African, European and Middle-Eastern cultures with a history of “dairying activity” dating back to the domestication of livestock 22 . Despite how it might otherwise appear through the lens of my own Euro-centric bias, dairy-products are essentially indigestible to the majority of adult humans worldwide 23.

What I was perhaps less concerned about then (than I am now) is that the primary driver of our large food corporations is maximising profit rather than optimising nutrition and providing diets that sustain health. I was certainly less aware of the widespread implications of this concern with profit at the cost of all else. It isn’t the case (as I once cynically believed) that westernised diets are bad for our health as a result of us being programmed by evolution to make terrible choices. The reality is that this is a victim-blaming fiction that draws attention away from the facts that there are vested interests, and weighty social factors 24 driving people to consume suboptimal diets that are bad for their health, bad for animals, and bad for the environment 25 .

My role in the food system was safeguarding the welfare of the animals going through the system, and I had considered that something worth doing. However, people can thrive on largely plant-based diets. If, as I came to suspect, it’s the case that these diets offer some of the healthiest and most environmentally sustainable dietary options anyway, the entire moral justification for killing, and particularly killing for profit, begins to crumble.

Since my newfound discomfort with the ethical acceptability of animal exploitation arose from my equally newfound understanding of the dynamics of socially normalised violence, it feels inevitable that I began to be gnawed at by the question: what are the links between and/or parallels with industrialised slaughter and the gender-based violence women suffer at the hands of men? Slaughter tends to be a very male dominated industry. I started pondering - is there some necessary mental disconnect that allows a slaughterman to spend his days chatting and joking with colleagues, whilst dismembering still-warm carcasses? Could this somehow be related to the systematised gender-violence I had so recently come to recognise?

Harming Women

It is so tempting to think of men who commit violence to women and children as aberrant monsters: to vilify, and in doing so to “other” them. The reality is that gender violence is far too widespread for us to reasonably consider it in any way abnormal. According to the World Health Organisation, globally, nearly one-in-three women and girls aged 15 years old or over have experienced either physical or sexual violence from a partner or sexual violence from a non-partner 26 . Endemic gender violence 27 has been described as “one of the most prevalent human rights violations in the world” 28. In the evocatively titled 2021 Oxfam briefing paper “The Ignored Pandemic”, gender-based violence 29 is described as “a global pandemic existing in all social groups across the globe” 30.

I envisage the socially unacceptable forms of gender violence - sexual and physical assault - as just the tip of the iceberg of the wider systemic oppression that women (and many others) face daily in the form of sexual harassment, power imbalances, microagressions and more. A 2021 study in the UK into the prevalence and reporting of sexual harassment of women in public spaces found that 86% of 18-24-year-old women report having been sexually harassed in a public place, and 93% of students are survivors of some form of sexual harassment but 98% of women aged 18-34 did not report these incidences of sexual harassment 31 . Much of the gender-based violence women navigate daily is invidious, insidious, and in many respects invisible, not because these things are rare, but because they’re so common, such a part of our social fabric, that we so often fail to recognise it as a form of abuse 32 , 33 .

I came to realise that it’s not monsters who assault women: it’s normal men, acting out our normal social scripts. So does this in fact bear any relation to the socially-normalised industrial slaughter of livestock? Are there in fact any crossovers?

Harming Animals

Certainly, there’s a well documented link between animal abuse and domestic violence, with animal abuse often found to co-occur with domestic violence 34. These studies however tend to focus specifically on cruelty to and abuse of animals. If we use Ascione’s 1993 definition of animal cruelty/abuse as “socially unacceptable behavior that intentionally causes unnecessary pain, suffering, or distress to and/or death of an animal” 35 , once again, (in addition to the perceived necessity) a key concern is the social acceptability (or otherwise) of the harm being carried out. There’s much more that can be said about the human harms of animal cruelty - from the concept of the “MacDonald Triad” (animal cruelty, fire setting, and childhood bed-wetting 36 ) being a predictor for antisocial/violent behaviour later in life, to the evidence that many serial killers “practice” torturing animals before graduating to human victims 37 , 38 , to the use of animal-abuse as form of domestic violence against a human 39 . The largely unstated assumption of all these studies is that they refer exclusively to “socially unacceptable” behaviour that intentionally causes the animal to suffer. They exclude by definition the socially sanctioned act of slaughter, about which one of the sanitising narratives is that it’s done as humanely as possible, in order to cause the animals concerned the least suffering possible.

But what of the damage to the humans conducting this sanitised “as humane as possible” slaughter? There are damning statistics which show that slaughter workers in the USA “suffer the highest annual rate of nonfatal injuries and illnesses and repeated-trauma disorders” of any private-sector industry 40 . Slaughterhouse workers experience a high prevalence of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety as well as substance abuse and "violence-supportive attitudes", and the vast majority have “limited educational attainment and come from a low socioeconomic background” 41 . These latter points are significant given "there is a social gradient in experiences of domestic abuse [and] income poverty is consistently reported as a key sociodemographic predictor of domestic abuse" 42 . There are also well-established links between the mental health issues and substance abuse issues that plague slaughter workers, and domestic violence perpetration (and indeed victimisation) 43 . There is a world of truth in the old adage “hurt people hurt people”. Perhaps we need to start recognising too, that in civilian life as much as in the armed forces 44 , 45 , “Hurting people (and animals!) hurts people”.

To explore this latter idea in more detail, Fitzgerald et al. researched “the effect of slaughterhouses on the surrounding communities”, looking for a “link between the increased crime rates and the violent work that takes place in the meatpacking industry”. Their hunch that the propensity for violent crime is increased by work that involves the routine slaughter of animals is known as “The Sinclair Hypothesis”, in reference to Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle about the exploitation of slaughterworkers in Chicago in the early twentieth century. Their study found “slaughterhouse employment has significant effects on [increasing the number of] arrests for rape and arrests for sex offences” in areas where meatpacking is conducted, even when controlling for a host of potentially confounding demographic variables 46 . The fact that the victims of the specific offences that are elevated by slaughter work tend largely to be women and children gives empirical backing to my own musings. The authors conclude these “social problems and phenomena … are undertheorised unless explicit attention is paid to the social role of nonhuman animals.” Doubtlessly, more research could be done.

In an unrelated study looking at the role of speciesism 47 as a marker for "inequality supporting attitudes", the authors came to the conclusion that their data “contribute to the growing body of evidence showing links between speciesism and prejudice. [This] shared emphasis on support for social hierarchy gives rise to a specific pattern of intergroup attitudes… that supports inequality” 48 . This evidence showing that speciesist attitudes - the very attitudes that allow a person to accept that is ok to kill members of species X for food, but entirely not ok to do the same thing to members of species Y - do indeed tend to cluster with other hierarchical, social-dominance supporting attitudes such as sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia etc. lends further support to my hunch that there are unrecognised connections between commercial slaughter and the systematic oppression of women by men.

For me, the important takeaway from this is summed up most eloquently by authors writing on a different topic entirely: climate change. In “Rethinking the Ethical Challenge in the Climate Deadlock: Anthropocentrism, Ideological Denial and Animal Liberation” 49 Almiron and Tafalla state that a major barrier to humanity taking the necessary steps to addressing climate change is the ideological anthropocentric denial of the problem by the mainstream/status quo/vested-interest-groups. Their position - that “the egalitarian, non-speciesist approach of the animal ethics movement… represents the next radical reflexive movement [which] could be used to break the climate deadlock” echoes my own thoughts that the same animal ethics movement might well be a transformative leverage point in terms of the within-species justice of gender equality as much as it is for between-species justice.

Following this vertiginous dive into the sexual and species politics of normalised violence, and the implications this had in both my personal and professional life, I did what any sensible person might do, and took a career break.

Part Two - Letting Go of Violence

Companion Animal Veterinary Practice

I resolved to move home to Wales to reconnect with my family. After some head-scratching as to how to support myself financially, I took a sideways career-step into companion animal practice on the basis that it was still working within my profession, but I’d at least be trying to keep some of my patients alive for a change. This move however simply brought me into what I’ve come to regard as another arena of animal exploitation. Counterintuitively, as a vet who feels strong empathy for her charges, I found the slaughter industry in many ways a less confronting environment than clinical practice. In what’s known to the veterinary profession as “small animal” practice, I was unable to reconcile myself to the chronic suffering of companion animals (primarily dogs) bred for physical deformities that left them in constant discomfort, and for which, if they were farm animals, the owner would be prosecuted as a breach of animal welfare legislation.

The now-classic example is French and English Bulldogs, pugs, Boston terriers and other “brachycephalic” breeds that have been bred for such extreme flat faces that they often require airway-surgery to assist them to breathe more easily. It is abhorrent to me that an animal should require corrective surgery to be able to breathe, when the root causes of the animal’s distress are the caprices of fashion. Harder still to accept is the tacit complicity of the veterinary profession. Bulldogs are so grotesquely deformed that they frequently cannot breed without intervention. By carrying out artificial insemination, and performing caesarean sections on these animals, my view is that the veterinary profession is guilty of perpetuating the parent animal's distress to subsequent generations.

Image: PublicDomainPictures, French Bulldog, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence

I am not a lone voice in saying that the many and varied chronic and debilitating conditions and complaints of inbred (“pedigree”) dogs are ethically indefensible 50. The British Veterinary Association (BVA) now has a policy position on brachycephaic dogs, and many vets, vet nurses and allied professionals campaign tirelessly to inform and educate the public on the welfare issues posed by terrible breeding practices. For me, personally, this came to feel like I was fighting the tide. I couldn’t do anything significant to make a change to the root cause of these animals’ suffering, and I was exhausted and burnt-out by the constant low-grade emotional distress of dealing with animals specifically bred for the very physical deformities that condemned them to a lifetime of discomfort. This contrasted markedly with my role as an animal welfare officer in New Zealand where I had been overseeing the care of healthy animals and I had the means to ensure any suffering they did incur would be short-lived.

After a short stint in corporate vet practice, I came to the conclusion that this was every bit as exploitative as the slaughter industry. In farming, at least this goal was stated upfront. In clinical practice, the fact that the entire purpose of the business was to generate the greatest profit for the shareholders was shrouded behind the rose-tinted notion that we all love puppies and kittens. This may be true, but it doesn’t make us (or indeed them) any less vulnerable to exploitation. I’d like to state explicitly here that I don’t for a second believe there are many other vets, nor vet nurses, nor veterinary-receptionists who conceptualise their roles this way. It’s probably not entirely normal to think of our entire society as an exploitation machine. Vets, vet nurses, and the auxiliary staff who’re so often the unsung heroines keeping these businesses on their feet, tend to be attracted to veterinary medicine because they like animals. The hours are terrible, the pay isn’t great 51, 52 , and, contrary to popular belief, vets (let alone vet nurses and the rest) usually aren't massively wealthy individuals. Nor, in my experience, do many vets have a huge amount of interest in (or time or energy left over to think about) the business side of a vet practice: we’re generally too busy worrying about providing the best possible care we can for sick and injured animals. My guess is this is probably how and why a lot of private practices have been bought up by corporate interests over the last couple of decades.

The Veterinary Profession

New veterinary graduate attrition rates are high. In 2021, over 45% of all the UK-based vets who left the profession had been practising for less than five years: over 20% of the vets leaving the profession had been in practice for less than a year before deciding to give up their registration 53. Given that it’s a five-year degree programme, and that the average debt UK vet-students incur by the end of this is approximately £70,00054, it’s a massive investment (and hard-earned identity!) to give up after less time than it took to train for it.

Within the veterinary profession, there’s been a lot of head-scratching about both the attrition rate and our far-higher-than-the-national-average suicide rate (a feature of the profession seen almost everywhere the research has been done including the UK 55, some European countries, the USA and Australia 56). I’ve heard several theories over the years that try to explain one or both of these phenomena 57, 58, 59, 60. Historically, to my mind, there hasn’t been enough attention paid to the degree of emotional discomfort and cognitive dissonance that can arise from caring deeply about animals whilst being instrumental to (and a benefactor of) their systematic exploitation for profit. A 2019 paper entitled “Moral Distress in Veterinarians” 61, raised the matter of moral distress as an area in need of greater attention in the veterinary profession. The authors use as an example the (oh-so-common!) scenario in which an animal cannot receive optimum treatment due to economic constraints (i.e. it isn’t profitable for the vet to treat the animal optimally!), and the distress this engenders in veterinary professionals.

Back to School

I was deeply privileged over the course of the COVID pandemic to be in a position to hang up my stethoscope for good, and study (from my living room) for a Masters degree in Sustainable Agricultural Technologies. This gave me a crash course in a range of agricultural disciplines, including agricultural ecology, soil science, and crop science, and an introduction to some of the most pressing issues in global food security, which have since become my preoccupation. Interestingly, whilst animal agriculture was certainly on the syllabus, my biggest takeaway regarding the industries in which I’d spent my entire career, was the disproportionate footprint of animal products over plant-based foodstuffs on just about every metric62. As touched on earlier, this is where I learnt that, whether we’re looking at outputs in terms of the gross weight, the protein content or the energy content of any given foodstuff, animal products tend to emit more greenhouse gases, use more land, and contribute more to eutrophication than plant-based foods - with exceptions being tree-nuts and certain pulses which use more land than poultry, eggs and some seafood 63.

Industrialised animal farming is doubly-damned: it’s awful for the sentient creatures involved, and it’s awful for the planet.

High-tech food-system solutions

In my hunt for a niche within sustainability research, I alighted on the revolutionary concept of cellular agriculture - particularly cultivated meat. Cellular agriculture has the potential to provide what is essentially an entirely new food-production technology, potentially largely divorced from the vast land-use (depending on how the various inputs such as cell culture media are produced) of conventional animal-sourced food production. NASA was one of the early players in cultivated meat research 64 and no wonder, given the promise this technology offers in terms of self-contained food production. The means to produce food in space is one of the (many!) challenges that would need to be overcome in order to realise long-haul space travel. As the title of the cold-war era economics tract by Barbara Ward “Spaceship Earth” 65 highlights - what is our planet to us, if not a self-contained life-support system travelling through space?

Image: WikiImages, Earth Moon Lunar Surface, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence

Cultured meat offers a way to bypass the harms inflicted on the eighty billion animals slaughtered each year for meat production 66 , whilst still providing for the ever-increasing global demand for meat 67. For the naively optimistic among us, this offers an ecomodernist land-sparing vision, where land could be freed-up from industrialised food-production systems, and turned over to carbon capture, rewilding, water cycling, and other essential ecosystem services, whilst reducing pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and decreasing the risk posed by food-borne and emergent diseases 68. Considered in these terms, the potential for good offered by cellular agriculture is vast.

But…

My exposure to the cultivated meat “startup” space brought a series of insights that, ultimately, have left me doubting, if not the theoretical benefits of the technology, then what good is likely to come out of its implementation in the real world.

To explain my concerns, let’s look to the great shining beacon of “how not to do things” that the USA offers the rest of the world, where Silicon Valley entrepreneurs are exuberantly “pitching” cultivated meat’s potential to investors 69. I remember the early days of Facebook, and the force-for-good it originally seemed to offer. Once upon a time, Facebook was a place to connect with individuals, rather than companies. It offered a means to maintain contact with people one might otherwise lose track of, and living overseas, it was a convenient way to keep family and friends “back home” up to date with the interesting bits of life (mainly cat and horse pictures!). In the wake of the 2016 US elections, Brexit, and the worrying swing to the right of many populist leaders worldwide, I found Roger McNamee’s book “Zucked” revealing. This provided a fascinating insight, not just into this particular company, but into the workings of our largely invisible Silicon Valley overlords. It crystallised my sense of there being a fundamental mismatch between the “values” I hold (one might say the ideology I subscribe to), and the capitalist pursuit of dollar-value at the cost of all else. My Facebook feed nowadays seems to be exclusively aimed at promoting products: it no longer contains anything personal to any of the people I care about. I don’t know if this is cause or effect, but I do know I’ve stopped seeing Facebook as anything other than an exploitation machine.

Google and Amazon have grown up into similar mega-monopolies. But these are technology companies, not food companies - how relevant are they really to the food sector? I suspect, when the food is produced by increasingly complex technologies, the answer is “lots”.

What is likely to happen with any powerful new food production technology, with the potential offered by cultivated meat, that’s owned by these same Silicon Valley overlords? Are they going to be interested in using it as a tool for reducing the harms to animals, people and the environment on which our current food system is contingent? Neil Stephens, a social scientist who’s been tracking the development of cultivated meat for several years, points out there are no explicit mechanisms in place to couple developments in cellular agriculture to any sort of environmental offsetting or mitigation of our current animal-rearing systems 70. He suggests that what might be seen instead is an “addition effect” where conventional animal agriculture outputs are supplemented by cultivated meat and overall meat consumption actually increases 71. I suspect that this technology, like Facebook, like Amazon, will be used to concentrate wealth and power even more into the hands of the elites, moving us more and more in the direction of a neo-feudal society.

This thought process led me to re-examine my equally naive stance on genetically modified organisms along the way. Hitherto, I’d always landed squarely in the “pro-science” camp and was a bit baffled by what I’d seen as “anti-science” stances. But then… As GMO debates have largely centred around modified crop plants, rather than modified livestock, I’d also had the privilege of not having to get too involved in them. As I studied sustainable agriculture, I learnt more about how GM technology has been used to facilitate vast monocultures of crops such as maize and soya, destined for animal feed and biofuel. When these crops are consumed directly by humans, it’s often in the form of highly processed commodities that make them essentially unrecognisable in the finished product: high-fructose corn syrups, corn starch, soya-oil and the like 72 - ingredients associated with unhealthy diets, and as a result the non-communicable diseases that kill 41 million people a year globally 73. I started wondering - who’s actually benefiting here? Is there something about these high-technology approaches that inevitably perpetuates inequalities? Or is it the case that it’s not the technology itself that’s at fault, but rather the uses to which it’s put? Maybe the thing that’s broken is our ideology? Perhaps the criticism of science and technology in this respect is unfair? But more importantly, perhaps it misses the point. And if, in sustainable food systems, as in veterinary medicine, if we fail to identify the root-causes, are we then only ever left with symptomatic management??

The way forward

I feel like I’m still trying to find a way to live that’s congruent with my values. Certainly, from the naively-utilitarian position of my meat-vet days, my stance has shifted a long way. I’m nowadays of the opinion that industrialised slaughter is not ok, and we need to stop. A pivotal part of my personal journey away from violence has been choosing not to kill. This decision on my part certainly hasn’t changed the world: industrialised slaughter continues unabated and global meat consumption continues to rise. Nevertheless, choosing non-violence as a practice has profound implications for how I live my life, both personally and professionally. Maybe there is something intrinsically worthwhile in navigating for ourselves the moral conundrums that impact our lives, and trying to find “better” ways to live as a result? Maybe there’s something meaningful in the invocation “do the virtuous deed without being attached to the outcome of your actions” 74? And if more and more of us choose to value living with moral integrity, whatever that means to us, and prioritising that over conforming to the social norms imposed by the status quo, perhaps that has the potential to create much-needed change?

Conclusion

Since starting this journey, I’ve come across many competing visions of sustainable food systems - some inspiring, some (to me) terrifying. Whilst the Rousseauian romantic in me loves to envisage what life might have been like before the dawn of agriculture, I’m well aware that any sort of “return to eden” that advocates for more of a “hunter-gatherer” style of living is in many ways an impossible fantasy 75. High-technology approaches such as cultivated meat are perhaps the opposite end of the spectrum to the hunter-gatherer idyll, but the social implications of ever-increasing concentration of power and wealth in the hands of a billionaire minority, and the continued widening of the gap between rich and poor that I suspect will accompany this doesn’t offer me much hope as a way forwards. Maybe, regardless of how much I like or dislike the idea of them, we have already reached the point where these sort of techno-solutions are an unavoidable necessity. I am inspired by a comment made by Julie Guthman in a recent interview. When asked what her ideal food system looks like, she made the point that she doesn’t think about “ideal” ones so much as “better” ones. She discussed the framing of utopia as a process of “what decisions can we make that lead us to a better place”. Drawing on that framing, my current process for moving towards a better food system is the same as that for moving towards better social, economic, political, and indeed ideological systems: find ways to reveal and ultimately reduce the embedded violence inherent to any given part of the system, and trust that whilst that may not lead us to something perfect, at least it will lead us in a direction that can be considered “good”.

Comments (0)