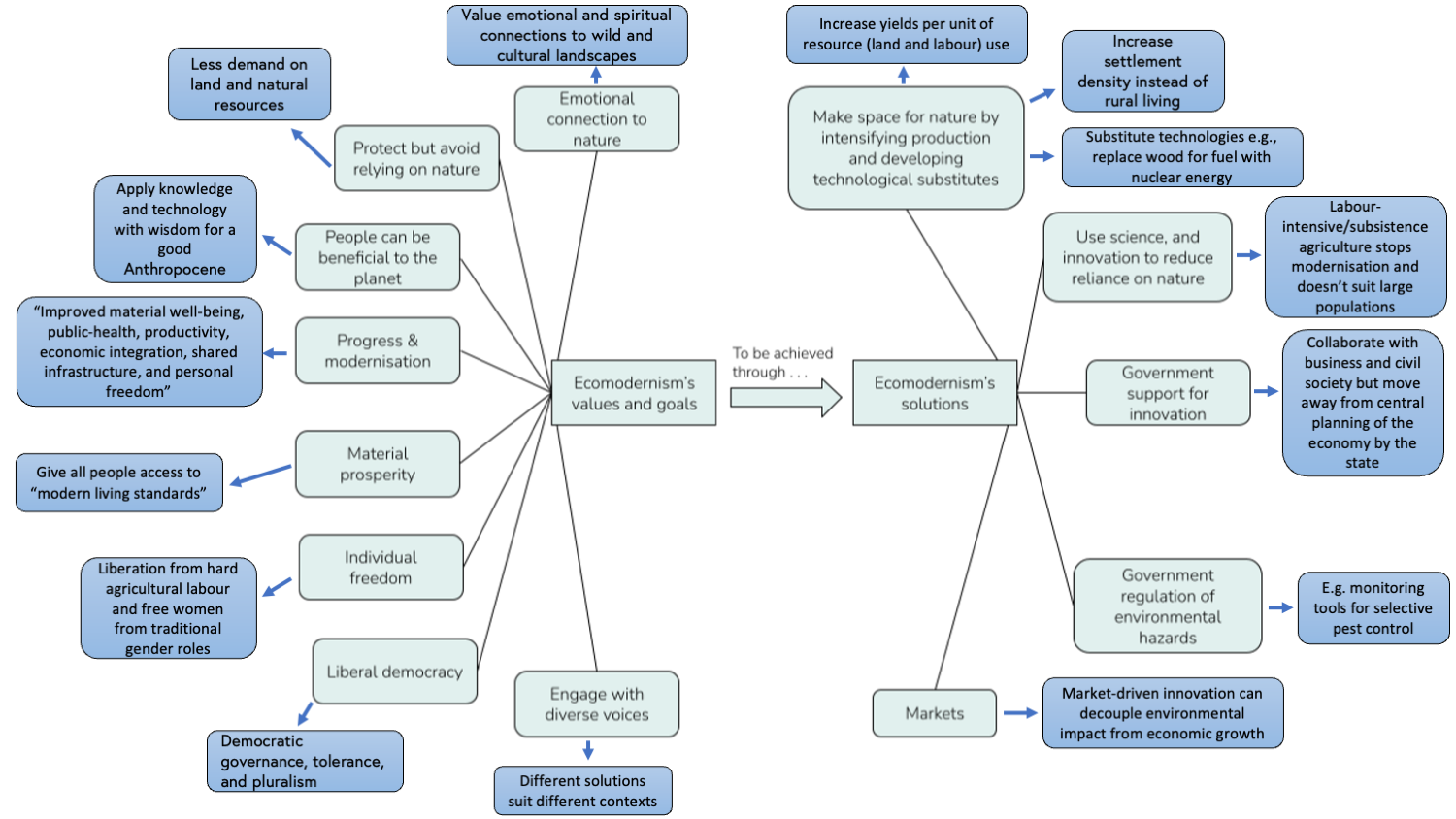

Debates surrounding ecomodernism

Ecomodernism provokes significant debate around both its evidence base and values. However, there is often a gap between how critics define ecomodernism, and how ecomodernists themselves define the concept. Moreover, individual ecomodernists may prioritise different goals and solutions. The discussion below highlights key points of tension between ecomodernists and their critics. It seeks to represent the various arguments and counterarguments of both sides whilst reflecting their differing perceptions of ecomodernism and the diverse views of ecomodernists themselves.

Debates around the evidence

Can decoupling keep us within environmental limits?

The 2009 planetary boundaries framework quantifies nine environmental planetary limits, including climate change and biodiversity loss. It argues that beyond these limits tipping points occur where natural feedback loops cause irreversible (on human timescales) shifts in the state of ecosystems or the entire planet (e.g. to a much hotter climate). Ecomodernists disagree with this framing; Nordhaus, Shellenberger and Blomqvist argue that six of these supposed planetary boundaries are not linked to global tipping points; moreover, any related “boundary” is arbitrarily linked to preferred states rather than objective reality. Instead, they prefer a regional (not global) approach to assessing impacts and managing trade-offs. Ecomodernists also question the value of placing hard limits on resource availability. They suggest that power sources like solar, wind, and nuclear can provide enough energy to meet growing demands, whilst technological innovations can produce substitutes for scarce natural resources. As such, they argue that theoretical upper limits for resource availability are too high to be meaningful constraints. It’s worth noting that this argument does not apply to materials for which few or no substitutes are available (e.g. certain micronutrients in agriculture).

Nevertheless, the Manifesto still concedes the risks of environmental damage and global tipping points in some categories, including climate change. Here, ecomodernists argue that we can ‘decouple’ economic growth, often measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), from increasing environmental impacts. Decoupling can be viewed both in relative and absolute terms. Relative decoupling occurs when environmental impacts continue to increase but rise more slowly than economic growth, whilst absolute decoupling means that total impacts decrease despite continued growth. Although more effective at preventing environmental impacts, absolute decoupling is less common than relative decoupling. Moreover, whilst The Breakthrough Institute reports that 32 countries have achieved absolute decoupling of economic growth from territorial and consumption emissions, a 2020 review concluded that the reductions in impacts are still not enough to meet stringent climate targets. Other criticisms are that increases in efficiency encourage rebounds in consumption (a phenomenon known as Jevons Paradox) and that a focus on economic growth shifts attention from the wider societal issues that underlie environmental damage and poverty.

Connected to the argument for decoupling are the Manifesto’s claims that richer countries are more resource efficient than poorer ones. However, critics dispute these claims: one response argues that megacities use a greater share of energy, and produce a greater share of waste, than their share of the world’s population. Meanwhile, several studies question the logic of agricultural intensification. For example, one study found that while intensification driven by technology (i.e., when technological development increases yields) can lead to global-level land-sparing, intensification driven by market demand (e.g., growing crops with a higher market value) causes land expansion and deforestation. The authors of this study suggest combining natural resource governance and technological intensification to halt deforestation (note this is also recommended by ecomodernists).

Is small-scale farming productive?

Ecomodernists claim small-scale farming is unproductive – pointing out the relatively low yields of farms in poorer countries and several-fold higher yields of farms in richer countries (where farms are usually large and intensified). However, critics state that, on the contrary, smaller farms, on average, have higher yields per hectare than larger farms.

To what extent can technology replace ecosystems services?

Ecomodernism advocates shifting from dependence on nature towards developing technological substitutes. However, ecomodernists acknowledge that not all ecosystem services can be easily augmented or replaced with technology. For example, whilst one could replace nutrient cycling to some extent with synthetic fertilisers or use filters instead of trees to remove air pollutants; replacing processes like photosynthesis and decomposition would be difficult. It should also be noted that the concept of ecosystem services is contested (see the full explainer for detail).

Debates around values

How cautious should we be about the unintended consequences of technologies?

Critics argue ecomodernism underestimates potential unintended consequences of technology, such as nuclear waste or global supply chain disruption. These are particularly unpredictable for novel technologies, especially if rebound effects on consumption patterns occur. Thus, environmentalists may suggest using the precautionary principle, and treading carefully when the impacts of a novel technology remain unclear. However, ecomodernists suggest two alternative approaches: A proactionary principle, which states that not using available technologies is more dangerous than being overly cautious, and the idea of intended consequences, which emphasises the risks of inaction and favours inclusive decision-making to identify and mitigate risks.

How important is material consumption for a good life?

Ecomodernists believe material prosperity (including energy access) is key to a good quality of life and therefore often favour preventing material poverty even if that increases environmental impacts. They put little emphasis on constraining consumption patterns, instead arguing for more efficient and less environmentally harmful strategies to meet societal demands. Whilst environmentalists agree with the need to reduce material poverty, many feel that ecomodernism simplistically equates wellbeing with material consumption, urbanisation, productivity, and economic growth. Degrowthers promote an alternative vision of progress, one less focused on material consumption and more centred on aspects like a sharing economy, shorter working hours, and greater community interaction. Certain critics also argue that ecomodernism pays too little attention to the benefits of living well while consuming less and ignores the additional downsides (on top of environmental damage) of high material consumption, such as the negative effects of excessive consumerism on mental health. Finally, critics suggest that ecomodernism underestimates how much income inequality (rather than average income) impacts health and social inequality in richer countries, and so misses the chance to alleviate poverty through resource redistribution.

Overall, critics think ecomodernism is overtly prescriptive in advocating for industrial modernity and higher material consumption. Meanwhile, ecomodernists argue that they merely seek to enable greater choice in how people live, work, and consume.

What is the best way to support social justice?

Ecomodernists often argue that material prosperity and social justice are fundamentally linked: many make the case that providing greater access to wealth and infrastructure is more effective than just focusing on inequality and its causes. One criticism is a lack of detail in the Manifesto on how to resolve long-standing structural power imbalances (e.g., systemic racism, sexism, and class divides), and how it arguably overemphasises the role modernisation and material prosperity might play in improve living conditions. Critics may also feel that progress to “fully developed capitalist service economies” is either impossible or undesirable for certain countries, since the wealth of richer countries depends (critics argue) on exploiting poorer peoples. All this being said, ecomodernist social justice ideals appear to be evolving (see The Breakthrough Institute’s 2021 special journal issue on Ecomodern Justice).

Does ecomodernism give power to corporations and states?

Some critics think large-scale, intensive technologies favoured by ecomodernism suit powerful, wealthy corporations who already have access to diverse resources. As such, ecomodernism is seen as entrenching a status quo of unjust or exploitative power structures. For their part, the Manifesto’s authors argue that modernisation is not synonymous with capitalism and corporate power and instead it denotes a broader process of social, cultural, economic, political, and technological development.

How should people interact with nature?

The Manifesto advocates using some land intensively to spare larger areas for nature conservation and restoration (a land-sparing model). Some criticise this “polarised” vision of clearly separated areas of “nature versus non-nature”. In response, ecomodernists state that they appreciate different communities will favour varying degrees of human interaction with “natural” areas. Critics also argue that ecomodernism’s focus on land-sparing relies on “outdated notions of nature as passive, pristine and only able to prosper apart from us”; this is a problematic trope, because historically it was used by state and colonial powers to justify violence (such as the ejection of Indigenous people from certain land areas in the United States). Many ecomodernists strongly reject this accusation and the Manifesto itself does not define a clear “pre-human” baseline to which landscapes can be returned.

There is also debate over why industrial societies might value nature. Certain ecomodernists argue that people care more about conserving nature when they no longer depend on it for physical wellbeing. Others argue that poorer communities that are dependent on nature lead the defence of ecosystems against actions by corporations or states. Moreover, the ecomodernist Ruth DeFries says, “there’s no intrinsic value to nature for most people and that’s okay”. Indeed, ecomodernists often depart from environmental movements that assign intrinsic value to rural living or nature, arguing that the associated traditional practices are sometimes unsustainable (e.g., excessive bush meat harvesting).

Should we centre humans or nature?

Proponents of deep ecology, a philosophy which believes that all living beings have inherent value regardless of their utility, and sentientism, which assigns moral worth to beings (humans, animals, AI) depending on their capacity to experience “suffering and flourishing” may criticise ecomodernism’s primarily anthropocentric approach. These movements may argue that ecomodernism is lacking because it sees humans as the only ones who should decide what happens to the natural world by denying it moral status. Arguably, these debates stem from the differing reasons ecomodernism and non-anthropocentric movements give for making space for non-human life to flourish.

Is ecomodernism overtly political? Does it matter?

Finally, there are concerns around ecomodernism’s political motivations. Critics argue that Nordhaus and Shellenberger (the Breakthrough Institute’s founders) have used their experience in communications, opinion research, and politics to construct environmental narratives that appeal across political divides to gain further support. The concern is that in so doing they have avoided less politically acceptable – but, in the eyes of critics, necessary – environmental measures, such as lifestyle change and reduced consumption in the affluent Global North. The counterargument to this is that emphasising alignment with widely held values presents a pragmatic approach necessary for environmental conservation to become politically successful in democratic countries.

Comments (0)