In early 2024, the MESA team held a workshop in Colombia. The discussion in the room framed the main similarities and differences in relation to nature for each of three agricultural approaches: organic agriculture, agroecology and regenerative agriculture.

Camilo Ardila Galvis joined TABLE in December 2023 as part of the team at the University of the Andes (School of Government) in Colombia. He holds a BA in Economics, MA in Development Studies and MSc in Agroecology.

Introduction

The need to transform food systems towards a path of sustainability and justice has been increasingly 1discussed over the last decade (Brower et al., 2020). While this transformation implies changes in dimensions of nutrition, health, social justice, human rights and equity, a fundamental component is the ecological impact of agricultural production systems.

This is especially relevant for Colombia giving its agricultural potential, its mega biodiversity, and the state of its natural resources. The Agustín Codazzi Geographic Institute (2012) has pointed out that the country’s current land use does not correspond to its environmental capacity: 15% of the soils are overused; 13% are underused; and 40% are eroded. In addition, MinAmbiente & IDEAM (2024) recently revealed that 23.6% of the national territory shows some degree of soil degradation due to desertification.2

Likewise, there is significant contamination of water, soil, air and food, mainly due to the high and inappropriate use of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, fertilizers and hormones. Colombia is one of the largest consumers of pesticides in Latin America, with an average of more than 10 tons per 1000 hectares of arable land, while the use of fertilizers reaches 4.8 times the OECD average (FAO, UE & CIRAD, 2022).

These data show the urgent need to switch agricultural production systems onto a more sustainable path, and to give more discussion space to transformative alternatives. Among these alternatives, three approaches have generated increasing interest in recent years: organic agriculture, agroecology and regenerative agriculture. (For more about these approaches, check out TABLE' explainers What is regenerative agriculture? and What is agroecology?)

Given this growing attention it is important to analyze the conceptual and practical differences proposed by each approach, as well as the actors who promote them and the narratives and interests that support them (as has been done by others such as TABLE, 2020; IDS & IPES-Food, 2022; Agroecology Coalition, 2024). Likewise, it is also relevant to identify which elements are in dispute, and on which elements we might find partial or total agreement, allowing for nuanced debates and common ground to strengthen calls to action.

Within this context, MESA Colombia organized a virtual workshop “Approaches to sustainable agriculture and its relationship with nature” in early 2024, which brought together 25 experts drawn from academia, agrarian movements, producers, NGOs and government. In the first part of the workshop, a panel of presentations were given on the definitions of each of the three approaches and how nature is understood within each one; this was followed by a participant discussion.

This essay draws on that workshop and some further reflection. In the following section, we present, first, a graphic analysis of the similarities and differences between the three approaches. Subsequently, we briefly describe the status of the approaches in Colombia, looking at their definition, and the policies and actors associated with them. Lastly, we delve into two areas of common ground for biodiversity action in agricultural systems, and two areas that remain in dispute.

Exploring similarities and differences between three approaches to sustainable agriculture

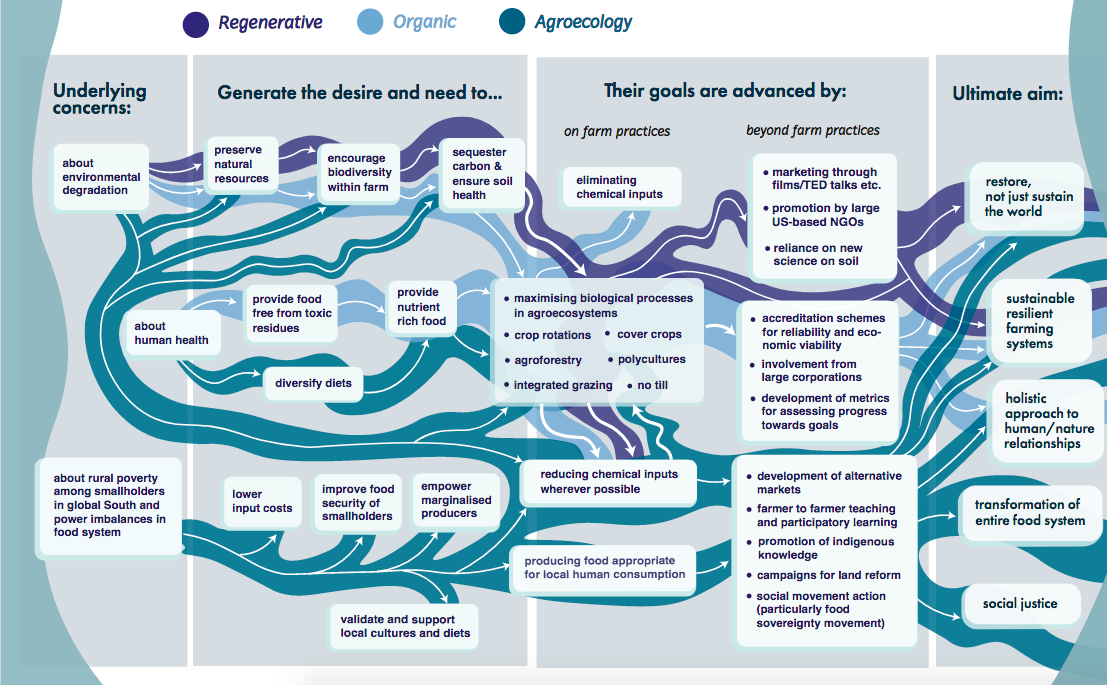

Regenerative agriculture, organic agriculture, and agroecology approaches share many concerns and offer solutions that seem similar. What does each approach offer that the others do not? And what makes one approach more prominent than another in certain geographic, economic, or historical contexts? Do they compete for space, or does their coexistence allow them to collaborate and advance their shared goals on a larger scale?

The diagram below emerges from these questions and represents an initial attempt to understand how agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and organic agriculture relate to one another.

Visualisation by Emily Liang. Explore the English version or Spanish version.

Overview of the three approaches in Colombia

Despite the positive contribution these approaches could make to the sustainability of agriculture and food systems (HLPE, 2019), Colombia lacks concrete and robust public policy instruments to help advance their uptake. Consequently, producers, communities or companies seeking to make a transition to production systems based on these approaches usually do so by their own initiative and means. Below, we present a brief overview of each approach in the country.

Customer buying onions with other vegetables in the background. Photo by Virginie-Sankara on Unsplash.

ORGANIC (ECOLOGICAL) AGRICULTURE -OA

In Colombia, the official term used to refer to organic agriculture is ‘ecological agriculture’, generating some confusion between this and agroecology1, especially in recent decades as agroecology has begun to attract greater attention beyond rural organizations and academia.

Organic agriculture (OA) has been formally present in Colombia since the mid-1990s. Certified organic agriculture has been regulated by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR) since 1995, going through several changes and adjustments before arriving at Resolution 187 of 2006 and its associated regulation, which constitute the current regulatory framework. While the regulation does not directly define OA, it indicates that an organic production system is a “holistic system of management of agricultural, aquaculture and fishery production that promotes the conservation of biodiversity, biological cycles and the biological activity of the ecosystem. This production system is based on the reduction of external inputs and the exclusion of inputs from chemical synthesis.”

These regulations also indicate principles, procedures and mechanisms for the scope and type of certification, which includes product categories and use of inputs, among others. However, the MADR is not implementing any program or differential policy for the promotion of OA, nor are there specific functions within its departments that provide guidance in this regard. While the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development has promoted this type of production under the “Green Business” program; and the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism has leveraged the international trade of organic products within the framework of trade agreements, efforts have overall been very shallow2.

Colombia does not have a robust information system that allows monitoring of organic actors, production and certification; SISORGÁNICO, which in principle is the system that would fulfill this purpose, is outdated and incomplete3. Despite this, some estimates suggest that in 2021 the country had an organic agricultural area of 100,874 Ha corresponding to 0.2% of agricultural land (FiBL & IFOAM, 2023), with coffee as the traditionally leading product, and other featured products including sugar cane and its derivatives, palm oil, and, more recently, some vegetables and fruits. This organic surface area is significantly smaller than that of other Latin American countries such as Argentina (4 million ha, 2.7% of agricultural land), Uruguay (2.7 million ha, 19.6% of agricultural land), Brazil (1.4 million ha, 0.6% of agricultural land), or Peru (374 thousand ha, 1.6% of agricultural land).

In recent years the MADR, with the support of international cooperation, has made progress in the review and adjustment of organic production regulations, and its promotion and monitoring instruments, but there is no concrete public progress to date.

In 2012 more than 20 agri-food companies, certifiers and non-profit agricultural organizations created the Federación Orgánicos de Colombia (FEDEORGÁNICOS) as a private non-profit entity that seeks to articulate a new industry around organic production in Colombia. However, some member commentators feel that this Federation has lost dynamism and legitimacy. Given that most Colombian organic agricultural output is destined for international markets in the USA, Europe and Japan, the actors that have dynamized this sector are mainly producers and agri-food exporters.

AGROECOLOGY -AE

Although agroecology has been practiced by peasant and agrarian movements in Colombia since at least the 1970s, and has been discussed, theorised and promoted within academia since the late 1980s (León-Sicard et al, 2015), its appearance at the institutional level is much more recent.

In 2017, the Resolution 464 of 20174, which guides public policy for Peasant, Family and Community Agriculture and was constructed in participatory fashion and led by MADR, became the first regulatory instrument that makes explicit reference to agroecology. This Resolution includes nine guidelines with specific actions for agroecology and establishes the official definition of agroecology currently in use in Colombia, explaining it as:

[A] scientific discipline, a set of practices and a social movement. As a science, it studies the ecological interactions of the different components of the agroecosystem, as a set of practices, seeks sustainable agri-food systems that optimize and stabilize production, and that are based on both local and traditional knowledge and modern science, and as a social movement, it promotes the multifunctionality and sustainability of agriculture, promotes social justice, nourishes identity and culture, and reinforces the economic viability of rural areas.

Since this Resolution, policy advances on agroecology have been slow. The MADR has made progress in gathering inputs and proposals with the support of international cooperation (GIZ in 2018 and FAO in 2020-2024). During the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP16) held in Cali, the Minister of Agriculture and various actors that participated in the preparation process carried out a symbolic signing of the public policy for agroecology in Colombia, which establishes the main guidelines and strategies for the promotion of agroecology in the country.

On the other hand, Colombia lacks robust data as regards the state of or trends in agroecology in the country. We do not know the number of farmers that implement agroecology; the number of farms or hectares; or the main agroecological production systems. Some partial approaches exist however, such as the mapping of agroecological processes carried out by the MADR and FAO (2024), which shows the presence of at least 714 collective agroecological initiatives (associations, markets, schools, etc.) representing more than 86,000 families.

Among the actors that have promoted agroecology in Colombia, the main ones are rural organizations of peasants, rural women and ethnic communities that have also been participating in the construction of the national agroecology policy and its national plan. Within the academic sector, the Network of Higher Education Institutions with Agroecology programs in Colombia (IESAC) stands out. It was formed in 2018 and is composed of nine institutions from different parts of the country. Several of these organizations and networks formed the Colombian Agroecological Movement Promotion Committee (CIMAC) at the end of 2023 as a “space for the articulation of networks of organizations, institutions and rural platforms interested in promoting and scaling up agroecology as an alternative to the civilizational crisis”.

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE -RA

Even though the term “regenerative agriculture” has been used in different countries since the 1980s, in part thanks to the work and dissemination of the Rodale Institute (a USA-based non-profit organization who initially coined the term regenerative agriculture), the last 10 years have seen exponential growth in the interest and use of this approach. Due to its relative novelty, regenerative agriculture (RA) does not yet have a formal definition (and there is indeed resistance to having one), as such, lends itself to diverse interpretations. As discussed by Cusworth & Garnett (2023), there are those interpretations that emphasize a particular set of practices; those that focus on desired or promised results; and those that primarily see RA as a mindset - as a new way of relating to each other and to the natural world.

In Colombia, use of the term is very recent. As noted, there is also no official definition, but most Colombian usages of the term tend to refer to RA as a set of practices. In particular, it is common to associate regenerative agriculture with practices such as: (1) limiting soil disturbance or alteration; (2) keeping the soil surface covered; (3) promoting agricultural diversity; (4) maintaining living roots in the soil; and (5) integrating livestock and crops.

For this approach, Colombia also does not have data characterizing producers, products or territories where it is being implemented. Much less is there a program or public policy that incentivises its practice.

Among the actors promoting RA are agro-industrial corporations such as Bayer, Yara, and Nestlé; in addition to some national producers and companies such as Luker and the National Federation of Coffee Growers, although with less emphasis. Some international NGOs such as The Nature Conservancy and the FOLU Coalition also include it in their work areas for the country.

Opportunities for action in favor of biodiversity

Despite the differences between these three approaches - theoretical, practical and in terms of public policy - there are important elements that could constitute common ground for action in favour of the sustainability of agricultural production systems, and of food systems in general. Having this in mind, in the aforementioned workshop we addressed the following questions:

- What are the common and opposing elements between the way in which each approach understands and addresses nature?

- Is there a common ground for research or action that benefits the three approaches? What elements does it include?

During the workshop, participants identified two main elements that AE, OA and RA share; and two fundamental differences. The shared elements are the search for and promotion of soil health, as a primary condition for agriculture; and the use, enhancement and restoration of nutrient cycles and recycling. The main differences concern the dimensions that need transforming within food systems, and the scale of production of each approach. Below, we delve into these elements based on the main arguments found in the literature of the three approaches.

Sprouts in healthy soil. Photo by Nora Jane Long on Unsplash.

SOIL HEALTH

For the workshop participants, all three approaches share an emphasis on soil health. Its importance is highlighted both in terms of biodiversity and for plant and animal production. Soil has a direct effect on human health (for example, through nutrition, security and infrastructure); the health of plants and animals (providing nutrients, water, oxygen and habitat); on environmental variables (quantity and quality of water, land use, carbon capture, air quality); and on healthy ecosystems (IICA, 2021). The importance of soil health lies in its "continuous capacity to function as a living system" (Ibidem). This becomes even more important when considering the degree of soil erosion and desertification in Colombia, mentioned in the introduction to this essay.

All three approaches establish soil health as one of their central principles or objectives. RA concentrates a large part of its practices on soil health, highlighting the importance of reducing mechanical and chemical soil disturbance. It also promotes maintaining soil cover to favour ecosystem restoration; and living roots in the soil, to increase carbon capture, greater nutrient availability, and greater soil aeration, drainage, and water filtration capacity (Cusworth & Garnett, 2023).

Similarly, AE positions soil health as one of its core principles (HLPE, 2019). Agroecological systems begin by restoring life in the soil in order to reestablish and improve the multiple ecosystem processes and services based on it, mainly through planning, managing diversity and optimizing biological synergies (FAO, 2015, 2018).

Finally, OA incorporates it as one of its main objectives, and it is evident in its definition as “a production system that maintains and improves the health of soils, ecosystems and people” (IFOAM, 2008). OA highlights the importance of maintaining fertile living soil; preventing wind and water erosion of soils; improving the infiltration and retention capacity of water; and reducing the consumption and contamination of surface and groundwater (IFOAM, 2020).

This shared understanding of the nature-soil-agriculture relationship implies the promotion of various common practices – cover crops, intercropping, crop rotations, zero or low-disturbance tillage, green manures, integration of crops and animals, etc. Moreover, it is configured as an area of public policy that supports the transition to more sustainable and natural production systems in Colombia, beyond whether these transitions are identified as agroecological, organic or regenerative.

NUTRIENT RECYCLING

Workshop participants pointed to nutrient recycling as the other common element between the three approaches in the way they address nature or promote more natural production processes. In addition to energy, organisms need inputs of matter, in the form of nutrients, to maintain their vital functions. Many of these, such as macronutrients, are mobilized through biogeochemical cycles, complex and interconnected processes that can occur at territorial or global scales, exceeding an ecosystem or a farm. The workshop pointed out that the concern of the three approaches for nutrient recycling reveals a different interpretation of the relationship between the productive system and nature, highlighting a relationship of interdependence and a recognition that the processes that occur on the plot or farm are mediated by natural processes occurring at multiple scales.

The three approaches propose nutrient recycling as an important component in the “re-naturalization” of the biological processes necessary for food production. This recycling usually involves the efficient use of organic waste, increasing soil organic matter and closing the nutrient cycle (Tully & Ryals, 2017); and can occur both at the farm and territorial levels through diversification and the creation of synergies between different components and activities of the agroecosystems (FAO, 2019). This recycling can significantly reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers thus increasing the autonomy of producers, reduce their vulnerability to market and climate disturbances, and mitigate climate change and soil degradation (FAO, 2019).

As mentioned above, Colombia is one of the countries in the region where synthetic chemical fertilizers are most widely used, with nearly 95% of these being imported. This situation makes the country’s agricultural systems vulnerable at an ecological and socioeconomic level. This was evidenced, for instance, by the increase in food prices in Colombia as a result of the disruptions in the trade of raw materials for fertilizer production following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022. In addition, fertilizers in the country can represent between 22.2% and 60.8% of the costs of agricultural inputs, and between 3.6% and 15.6% of total production costs (BMC, 2024). In this way, nutrient recycling becomes not only an environmentally beneficial strategy but also an economic one.

DESPITE THE COMMON GROUND: DIFFERENCES IN DIMENSIONS AND SCALE

Even though we have pointed out some common ground between the three approaches, there is also a terrain in dispute, differences that the promoters of each approach often identify as great distances or even irreconcilable elements.

The main difference pointed out by the workshop participants relates to the dimensions that each approach considers necessary to work on for food systems’ transformation. On the one hand, the promoters of AE emphasize that it seeks the transformation of the whole food system (Méndez et al, 2012) in its productive, economic, environmental, socio-political and even ethical-spiritual dimensions (Toledo, 2022). RA, on the other hand, seems more concerned with technical-productive or environmental changes than with the political and social dimensions. Despite the fact that there seems to be different "types" of RA with different degrees of association with AE; the latter appears to be much more comprehensive than RA, not only in socio-political aspects but also in biophysical dimensions (Tittonell et al., 2022). Moreover, some corporate versions of RA often offer a political vision of the future of food close to the status quo, with the dynamics between consumer, producer, distributor and processor virtually unchanged (Cusworth & Garnett, 2023).

The differentiation between the dimensions of change promoted by AE and OA is more diffuse, especially if we look at the principles and strategies that each promotes - from where they can be considered as related approaches (HLPE, 2019; IFOAM EU, 2019). However, a point of tension relates to certifications. The adoption of OA by producers, researchers and governments has generated the need to define minimum requirements, thresholds and verification of their compliance, which has not occurred so explicitly in the case of AE. These minimum requirements have motivated an increasing number of actors to enter the organic sector and only meet the legal requirements to obtain a third-party certification (e.g. replacing inputs without redesigning the agroecosystem and its operations); which has generated alerts about a possible “conventionalization” or “standardization” of OA (Darnhofer et al., 2010).

These differences in dimensions are reflected in the different actors that support or promote each approach in Colombia. The multidimensionality of change highlighted by agroecology corresponds to the multiplicity of actors that promote it - peasant organizations, ethnic organizations, universities and some government sectors. This multidimensionality and diversity of actors is also found in OA, although with a preponderance of actors oriented towards agro-exportation. Finally, the productivist emphasis of RA, and its relative newness, is reflected in a smaller and less diverse number of actors - mainly international corporations.

Another tension or difference between the three approaches that was highlighted refers to scale. AE has been based primarily on small-scale, labor-intensive farm production in the Global South; and while there are numerous examples of its application on large farms, significant challenges remain in terms of research, technology and policy development for a transition to agroecology in large-scale agriculture (Tittonell et al., 2020). OA has had a greater variety of scales and typologies of producers, from diversified small-scale vegetable production systems to large-scale organic monocultures (e.g. sugar cane). However, organic production is often concentrated on larger farms. For example, in the European Union – which is the region with the largest amount of land under organic production after Australia (FiBL & IFOAM, 2023) – the average size of a fully organic farm was 2.4 times the average size of all agricultural holdings in 2020 (EUROSTAT, 2024). Finally, in its different versions, RA has attracted a diversity of actors ranging from small-scale producers aligned with alternative agriculture to large transnational corporations (Cusworth & Garnett, 2023). However, the latter are the ones that have promoted and made RA most visible in the Global South. Ultimately, the importance of scale also relates to the actors who could benefit from policies aimed at strengthening one or another approach.

Final reflections

The transformation of food systems requires changes at different levels, areas, actors and processes, from small-scale incremental changes to structural transformations in cultural, institutional and political patterns.

The systemic nature of this transformation can seem overwhelming for those with a mandate for change, but who only have governance over one dimension, process or actor of the system. This is the case of ministries of agriculture, for example, which are largely focused on agricultural production, but which often have stakeholders with different, and even opposing, interests or values.

Faced with this challenge, an essential question is where to start. To address this question, we consider it essential to start with what unites us, and not with what differentiates us. By identifying the common ground between different, and even opposing visions, it is possible to begin the transformation while the political process that requires more structural transformations, and on which there are important differences regarding objectives, interests or values, develops in parallel.

It is important to clarify here that we do not intend to generate a false sense of alignment between the three approaches, nor to promote universalist solutions ('putting everyone in the same box'), since one of the main causes of the crisis in the food system is homogenization (of production systems, diet, values). On the contrary, we consider that, only after recognizing the diversity of visions and values on the necessary changes in agri-food systems and their possible paths, can we start to work around the common ground, if any.

In this essay, we have highlighted how AE, OA and RA, despite their differences, propose and promote methods and systems that prioritize soil health and the recycling of nutrients and biomass, as important elements of more natural agricultural systems. These areas could be fertile ground for governments and other actors to generate incentives and support for producers, communities and companies without narrowly specifying which path they wish to follow to advance towards sustainability; organic, regenerative or agroecological.

Comments (0)