This report details the interconnectedness between food and fossil fuel consumption through the entire supply chain. The authors identify the key drivers of food system fossil fuel consumption, barriers to transformation and high-impact, no-regret opportunities to collaborate in the transformation of energy and food systems.

Summary

Transforming food systems through reducing the demand for fossil fuels will play a central part in countries goals to meet emissions reduction requirements. The authors of the paper found that the agrifood system currently drives as many emissions as all EU countries and Russia combined and that agrifood system transformation could reduce global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 10.3 gigatons a year (20 percent of the cut needed by 2050 to stay below 1.5°C). A large part of these emissions come from the complex connections between the fossil fuel industry and the industrial food system, which the authors estimated uses 15% of global fossil fuels annually. There are four fossil fuel hotspots in the food production value chain; input production; land use and agricultural production; processing and packaging; and retail, consumption, and waste. Processing and packaging accounts for an estimated 42 percent of energy in the food system because of the reliance on energy-intensive equipment, refrigeration and transportation. Energy intensity in this stage is projected to increase with more mechanisation, globalised supply chains; and growing demand for meat, dairy, and ultra-processed foods. Inputs and agriculture production together account for a further 20 percent of energy use, with land use and agricultural production accounting for about 15 percent and input production (excluding transportation) accounting for about 5 percent. It is important to note that whilst fossil fuel emissions from land use change and agricultural production might be relatively small, the overall greenhouse gas emissions from this stage is amongst the highest due to the warming effects of other greenhouse gases (primarily methane and nitrous oxide). Crop production energy is used in irrigation, mechanical processes, input distribution, heating and drying harvests. Fertiliser production, particularly synthetic nitrogen, accounts for the majority of input energy usage. Due to the close connection between fossil fuels and food, collaboration between actors within these two systems is crucial.

Future projections estimate that food trends will heighten energy intensity. Firstly, global food demand is expected to increase by 35-56 percent by 2050 (from 2010), potentially leading to massive increases in fossil fuel based inputs. Secondly, ultra-processed foods, whose production is 2-10 times more energy intensive than whole foods, are dominating high-income countries and rapidly increasing in low and middle-income countries. Thirdly, increasing globalised supply chains, mechanisation and increasing demands for meat are driving increased energy use in low and middle income countries. Finally, although potentially beneficial across a range of sustainability indicators when compared with equivalents, there are open questions about the energy intensity of alternative proteins, which many see as a panacea for a sustainable food system.

As with other industries, vested interests are resistant to phasing out fossil fuel usage in the food system. As demands for fossil fuels in transport, power and heating decline, companies are investing significantly in petrochemicals to produce plastic and agrochemicals. Agrochemicals, including fertilisers and pesticides, and plastics, including for packaging, are key to sustaining some industrial food systems activities, and the fossil fuel industry is banking on their growth to sustain profits. It is estimated plastic will drive almost half of oil demand growth by the mid century. Fossil fuel industries across the world are creating new facilities and expanding capacity to meet growing demand for plastics: investments of over USD 164 billion are planned between 2016–2023 in the United States alone. Food-related plastics and fertilisers together represent approximately 40 percent of petrochemical products. Both the energy sector and agrifood are dominated by a small number of large, vertically integrated, multinational firms with a vested interest in maintaining the current fossil fuel and chemical-dependent industrial food system. Addressing fossil fuel use in agrifood will therefore also require addressing this concentration of corporate power and taking measures to improve participation and agency for marginalised groups.

Food systems are also producers of energy through biofuels, biomaterials and on-farm energy. When considering the interconnected transition of energy and food systems, negative impacts of these energy sources need to be addressed. Production can have negative effects on local communities, remove land from food production, change land use patterns to increase GHG emissions, put pressure on other natural resources, increase food costs and potentially even be worse for the climate than gasoline energy.

In order to accelerate the transformation of the two systems, synergies need to be identified and actions identified that reduce fossil fuel consumption whilst maintaining or improving other food system outcomes such as food security and nutrition, improved livelihoods and healthier environments. The authors emphasise that agriculture and food systems don't just need to reduce fossil fuel consumption, but also need to become less energy intensive overall. As a result they warn that many ‘techno-fixes’ such as green hydrogen and genetically modified crops are contentious as they lock-in practices that rely on a highly energy intensive system, create negative externalities for nature and the environment, and further consolidate the concentration of power and profit amongst a few multinational companies.

The authors highlight the following ‘high impact, no regret’ actions for greater collaboration on the food-energy nexus:

- Phase out fossil fuel–based agrochemicals and transition to regenerative and agroecological approaches;

- Review fiscal policies to counter the negative externalities of bioenergy production;

- Shift to renewables-based cooling, heating, and drying technologies;

- Shift to renewable energy for food processing and transport;

- Ensure healthy, sustainable, and just food environments that support plant-rich diets and minimally processed foods;

- Track and address corporate consolidation in the agrochemical and food industries while actively supporting a just transition through more inclusive and equitable governance and decision-making.

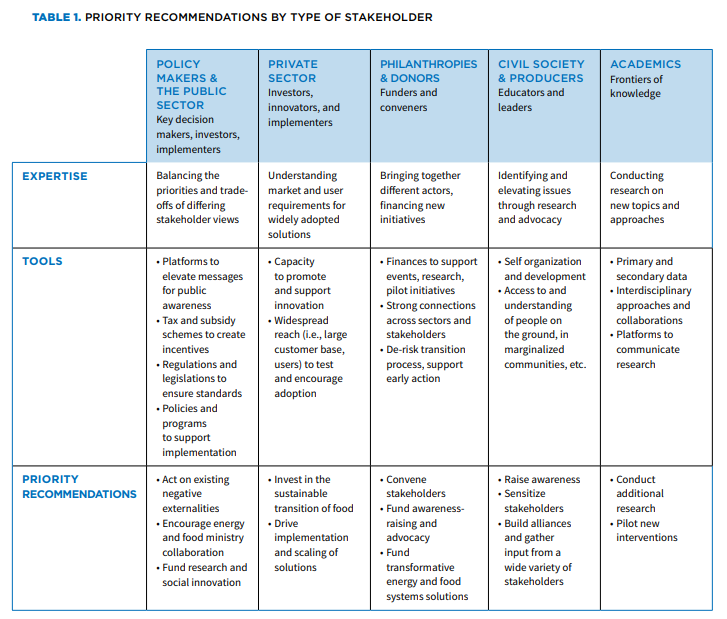

Specific recommendations for stakeholders are detailed in the table below:

Reference

Global Alliance for the Future of Food (2023). ‘Power Shifts: Why We Need to Wean Industrial Food Systems of Fossil Fuels’, Global Alliance for the Future of Food.

Find the report here and for more on energy, food and technology see our ecomodernist explainer

Post a new comment »