Smallholder farmers, pastoralists and indigenous people face unprecedented threats to their land, according to a new report by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES FOOD). The report explores the different drivers of land grabbing such as the fight for water and actors such as carbon off-setters and reveals that 1% of farms account for 70% of global farmland.

Summary

The report argues that the financial crisis in 2007-2008 unleashed a wave of land acquisitions in the Global South led by investors, agribusiness and sovereign wealth funds. As the crisis eased, these pressures didn’t disappear and more emerged – including conservation efforts, carbon offsets, and the rush for natural resources such as water and renewable energy materials. This ‘land squeeze’, as the report coins it, is reducing access to land in the Global South, undermining food security and violating human rights.

The authors say these trends are now creating a “dangerous interface between small-scale farmers on one side and institutional investors, fossil fuel companies and real estate developers on the other.”

They synthesise this land pressure into four categories; land grabbing 2.0, green grabbing, expansion and food system reconfiguration.

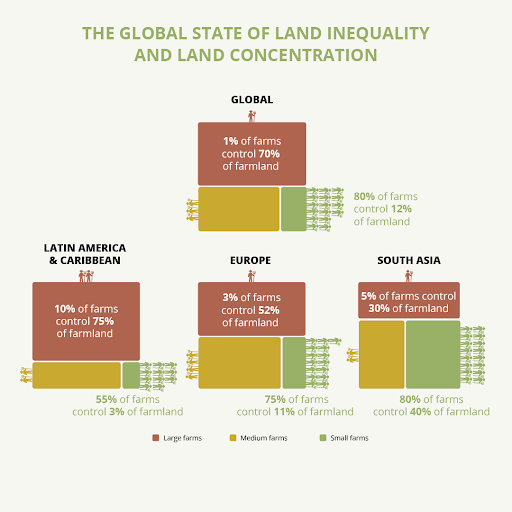

Figure 1: Infographic showing state of land inequality around the world.

The author of the report clarified to TABLE that the global figure is not an average of the regional figures and is based on the total farm numbers and farmland. The author says that this is because the biggest 1% of farms globally are large-scale farms, mostly concentrated in a few regions (including Latin America, North America). Within their own countries and regions, they are big relative to the average farm size but those large-scale farms are even bigger relative to the average farm size globally, especially in Africa and South Asia where average farm size is still around 2 hectares.

Land grabbing 2.0

Governments face increased pressure to deregulate land markets. In Africa and Asia, land is being expropriated through special economic zones and growth corridors. Water and resource grabs – deals to control water – are becoming more frequent, and used to grow water-hungry crops for export and biofuels. Land as a financial asset has become more attractive for powerful actors and agriculture investment funds have increased by 10 fold between 2005 and 2018, driving land inflation.

Green grabbing

With the advent of carbon and biodiversity markets, interest in conservation, carbon removal and offsetting is high and now accounts for 20% of large-scale land acquisitions. The authors say governments and large corporations are appropriating land through conservation schemes that exclude local land users and small-scale food producers, such as those on the frontline of climate change. These include carbon and biodiversity offsets, and large-scale (non-biodiverse) tree planting schemes. The report says governments have pledged to allocate land areas equivalent to total global cropland – almost 1.2 billion hectares of land. It also highlights that major protagonists of these acquisitions are fossil fuel companies and will bring control of forests under major polluters.

Expansion and encroachment

Mining, urbanisation and mega-infrastructure projects are ramping up the pressure of global farmland. Over the last 10 years, 7.7 million hectares of farmland have been lost, accounting for 14% of recorded large-scale acquisitions according to the report. These land conversions are particularly damaging for food producers and communities – causing mass displacement, land conflicts, and degradation of surrounding environments.

Food system reconfiguration

The report says the ongoing spread of industrial farming erodes how smallholder farmers use and control their land. Integrating smallholders into corporate value chains locks them into precarious livelihoods, unsustainable land-use and effectively forces them to “get big or get out.”

The impacts and solutions

The report says the emerging land squeeze is a vicious cycle. It exacerbates rural poverty and livelihood pressures on small-scale farmers, creating vulnerability to various forms of land appropriation, and paving the way for further land concentration, fragmentation, and degradation.

To stop the land grabs and encourage land equality, the report makes three recommendations:

- Inclusive governance mechanisms are required to bring together different policy imperatives, reconcile competing land uses, and place local communities and human rights at the heart of decision-making.

- Reduce the power of speculative finance in farmland to stop powerful actors flooding the farmland market.

- Access to land and secure tenure must be combined with structural support for small-scale food production; pensions, insurance, and debt relief for farmers, investment in rural infrastructures, and an end to harmful trade liberalisation.

Read the full report here.

Reference

IPES-Food, 2024. Land Squeeze: What is driving unprecedented pressures on global farmland and what can be done to achieve equitable access to land?

Comments (0)