It’s officially ‘climate season’, the nickname given to the autumn period, that’s jam-packed with climate conferences. The season kicked off in September when over 100,000 people participated in New York Climate Week, professionals flocking to the city alongside diplomats for the UN General Assembly that takes place in tandem.

It has already been a busy time for food and we still have COP16 and COP29 to come. Representatives at the UN General Assembly agreed to the Pact for the Future, supposedly to “bring multilateralism back from the brink”. In our summary, we highlight how the arduous negotiations led to a diluting of the text on food systems.

Tilt Collective, formerly known as PlantWorks, and SystemIQ have launched their new report, alongside a TED Talk (link to our summary) arguing that investments in a plant-rich diet could deliver five times the reduction in emissions per dollar than renewable energy. Read more here.

The fossil fuels in our food was another subject of discussion at Climate Week. Anna Lappé, director of the Global Alliance for the Future of Food, warned about the threat of fossil fuel expansion into food systems at a panel with Food Tank:

“As the fossil fuel industry feels the political pressure, they’re looking for other pathways. As we’re electrifying the grid, they’re thinking what else can we do with oil and gas? They’re thinking we can make petrochemicals into plastic, we can make pesticides, we can make synthetic fertiliser.”

If you want to know more about this, stay tuned for our new podcast series, Fuel to Fork, investigating the fossil fuels in our food with farmers, chefs, scientists and campaigners. Can we phase out fossil fuels and what are the powerful forces standing in the way? Click here to subscribe to the series, starting on the 24th of October.

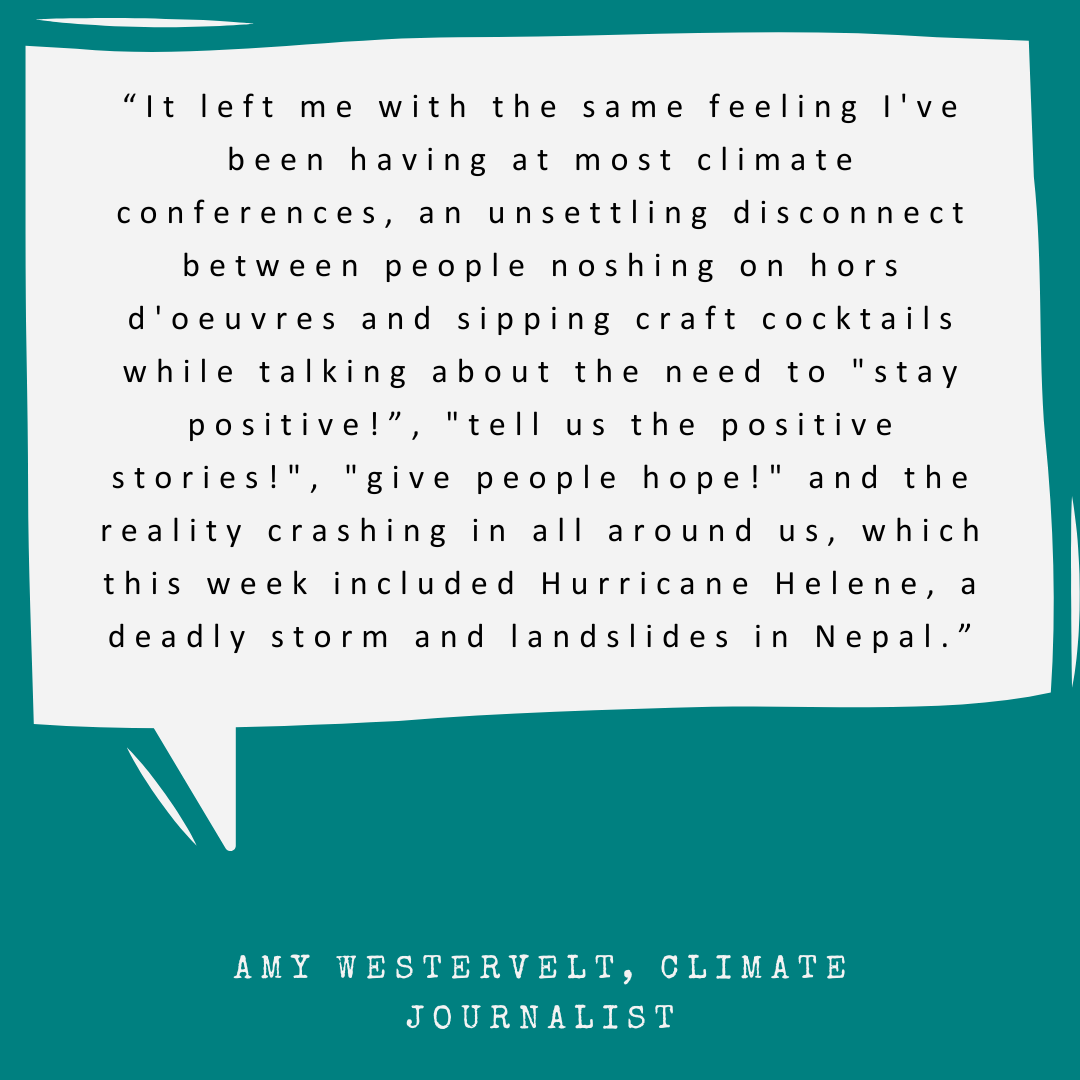

Another observation that resonated widely at Climate Week was the focus on solutions and positivity and a tendency to ignore the desperate state of global warming. Climate journalist Amy Westervelt described the dissonance between the obsessions with solutions and the extreme weather wreaking havoc globally as “toxic positivity” in an op-ed.

In this edition of Fodder, we explore the tendency to confuse hope with positivity in climate communications. We speak to Rachael Orr, CEO of Climate Outreach, an organisation specialising in climate communications to find out what’s the right balance to strike between crushing realism and positivity.

TABLE: We often hear that doom and gloom around climate change doesn’t inspire action, but do you think it’s gone too far the other way based on your experience at New York Climate Week?

RO: That's certainly true, people don't connect with a doom and gloom message. Climate Outreach has been doing research about how people think and feel about climate change for 20 years and it all says, that is absolutely right.

But what's happened in a culture of kind of overly positive messaging, there is a tendency to conflate positivity with hope.

We can't tell people that this future is already doomed and that we are set to fail because then why on earth would people be motivated to change things? But what we can't do is sugarcoat reality and say that this is going to be easy or this is all green fields and sunlit uplands. We have to be really honest with people about the scale of the challenge and about the trade-offs, but we have to offer them hope and we have to tell them that a different future is possible.

TABLE: What are the ingredients for powerful climate communication?

RO: It has to give people a sense of connection and agency. I think too much of our climate communication feels very distant from people’s lives, whether it’s doom and gloom or relentlessly positive. It has to have a sense of connection – this is how it will impact on your life or how it could be useful for your work.

Our advice is always how do you put people in the picture. Too often, climate change is a science story; it's about emissions and reductions and percentage of degrees and that's not what climate change is about in people's daily lives.

People are 22 times more likely to remember a human story than a statistic so I'm bad at remembering statistics but I remembered that one.

TABLE: Is food a good entry point to talk about and connect with climate change?

RO: Food is a really powerful way to connect but I think a lot of the communication that's linked food and climate has been more on a kind of guilt narrative. You have to stop eating meat or you have to be a vegan or that's how people have heard it. There are ways to have more conversations that are much more about connection and agency. Most people love food and if you can't afford to feed your family sufficiently it's an incredibly, you know, emotive and difficult situation.

We did a big piece of research called Britain Talks Climate (a survey of over 10,000 Britons and a very useful toolkit for climate communications) to understand how different people in the UK think and feel about climate change. There were lots of differences but something that came through really strongly was this has to feel like it's a collective endeavour. It has to feel like whatever I do, whether it's thinking about eating less meat or cycling to work or you know getting my kids’ school to have meat-free Mondays, I have to feel like that is in some way contributing to something bigger. We can't just focus on individual actions.

TABLE: Is there a difference between communicating climate change for the general public and for professionals, people who are knowledgeable and invested in climate action?

RO: I think it's even more important that those professionals feel confident in themselves in being powerful climate storytellers. I was at a panel during Climate Week about storytelling, there was a minister from Malawi and she talked really powerfully about being in an intense negotiation room where she was surrounded by white men in suits talking in very technical language. She gave a couple of stories about people in the communities that she represents about how climate change was affecting them and how they were doing community-level adaptation and she talked about the power of that story in that room. So, I think that lots and lots of professionals need to be brilliant climate storytellers and sometimes we hear too much technical language or exclusively technical language from them both amongst themselves and when they're then talking to everybody else.

One of the things we talk about with climate scientists and business leaders, we encourage them to start with your personal climate story. Why are you doing this job, what motivated you to be standing here? That sort of human story can sometimes make people feel a bit uncomfortable but it's really powerful.

Post a new comment »