The report, produced by Nature Friendly Farming Network and the Wildlife Trust, finds that a modelled reduction of farming inputs; pesticides, fertilisers and animal feeds, would result in commercial gains for 165 UK farmers. They refer to this balancing act as the ‘Maximum Sustainable Output’ -- the point where a farm achieves maximum output while harnessing the natural resources available to it.

The report presents evidence from 165 UK farmers who staged strategic reductions in agricultural inputs (pesticides, fertilisers and off-farm animal feed) to achieve the ‘Maximum Sustainable Output’ (MSO) of the farm – the point where a farm obtains maximum output while using the natural resources available. Analysis carried out by Nethergill Associates found that farmers not only made a financial gain if they followed this approach but such measureswould also improve farmer wellbeing, reduce farming emissions, and enhance natural assets and farm resilience to international markets and extreme weather.

The report highlights the current challenges that farmers face and the fragility of intensive farming production in relation to recent events; conflict in Ukraine increasing synthetic fertiliser prices, Brexit-related labour shortages, soaring agricultural inflation and extreme weather caused by climate change.

Maximum Sustainable Output is a metric for analysing the holistic success of a farm business. To identify this point, it considers the farm’s physical limitations; i.e. soil type and land area, and separates agricultural inputs into ‘productive’ variable costs; essential costs incurred when producing within the confines of nature, i.e. seeds, and labour, and ‘corrective’ variable costs; “avoidable or non-essential” inputs to produce above what is possible using natural resources, i.e. artificial fertiliser, pesticides, bought in feed. The MSO is always modelled on the point where corrective costs are eliminated. It claims that the gain of revenue due to eliminating these costs is alway greater than the loss due to reduced output. The report highlights that the MSO is not static because it is a function of physical factors which can change over time.

The concept of MSO was created to counter the idea that increasing outputs will always result in a rise in profits. Instead, it aims to show that farms reach a point where inputs are reduced and output is maximised while efficiently using their natural resources.

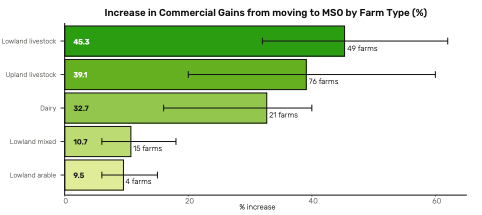

The research was conducted over 5 years and based on interviews of 165 farms of varying production systems –76 upland farmers, 49 lowland livestock, 21 dairy farmers, 15 lowland mixed and 4 lowland arable. The report does not say why the sample was skewed towards livestock farmers. Modelled results showed that lowland livestock made the biggest commercial gain byshifting to an MSO approach, with a modelled 45.3% average increase, while lowland arable made the smallest average gain of 9.5%.

Figure 3 shows the impacts of moving to MSO on commercial returns based on the sample of farm accounts assessed.

The reporthighlighted that a move towards MSO could have implications for food security – the modelled analysis showed a 22 – 29%reduction in of productive output, but the authors predicted that this reduction would not be as significant because of the increases in natural asset capacity; soil fertility, biodiversity and reduced soil erosion would smooth out yield fluctuations over time because of increased resilience. The authors cited the UK government Food Security Report from 2021 that said biodiversity and climate change are existential threats to the long term capacity to produce food. Thatreport said that food security rests ultimately not on maximising domestic production but on making best use of land types and sustainable production methods, ensuring the UK’s long term food security by protecting the natural capital embedded in healthy soil, water, and biodiverse ecosystems. It highlights studies that support this argument, such as one that found pollinator loss over 10 years would lead to £188 million yield loss and another that said setting aside 8% of farmland to promote wildlife could maintain crop yields due to increased biodiversity. This argument on food security relied on the assumption that the UK would shift livestock production to pasture-based systems, freeing up 40% of cropland currently used to grow animal feed and could be used to grow crops for human consumption. While the report does not address how decreases in output could lead to higher imports from abroad, the authors stress that a resilient domestic food supply depends on financial viability for farmers and a move towards MSO could achieve that.

Reference

Clark, C. et al. 2024. Farming at the sweet point. NFFN & The Wildlife Trust.

Read the full report here and see our explainer What is regenerative agriculture? and our interactive diagram about Exploring the ebbs and flows of Regenerative Agriculture, Organic and Agroecology

Comments (0)