Less and No Meat: A gendered and colonial divide

One deep dividing line between the different meat futures concerns views on animal suffering. The histories of feminism and animal liberation are deeply intertwined, as we see when we look at the origins of modern secular vegetarianism and its relationship with the women’s suffrage movement in the 19th century.1

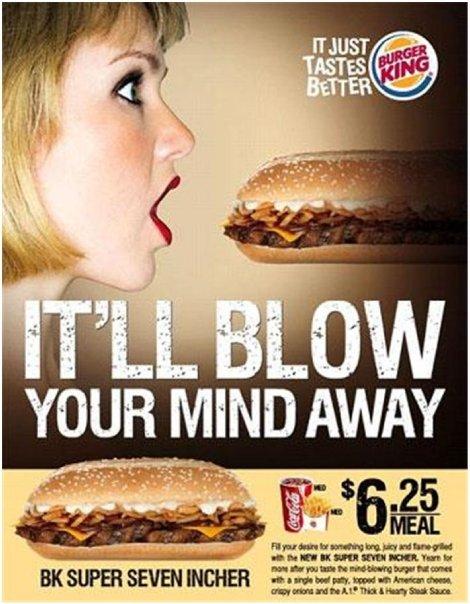

One scholar who advanced our understanding of the link between the suffering of women under patriarchy and that of non-human animals under speciesism is, of course, Carol J. Adams, whose book The Sexual Politics of Meat remains an influential text three decades after its publication. For Adams, the consumption of non-human animals and the sexual domination of women each stands as a reinforcing analogue of the other. Female bodies and animal bodies are both depersonalized, with the “referent” — the experiencing self — removed, and desire focused on disembodied body parts — breast, leg, and back. Adams notes how the metaphor of meat-eating is often used to describe male sexual desire and violence and the metaphor of meat to describe sexualized bodies. Meat, in turn, is often advertised with sexual imagery.2

In this cultural context, it is unsurprising that the argument that we should consider human violence towards animals as ethically similar to violence towards other humans lands very differently for different people. (The TABLE blog Use, Misuse and Abuse - a vet reflects on animal exploitation further explores the links between domestic violence and violence towards animals.)

But for some thinkers, the social liberation movements of the last two centuries — feminism, racial justice, socialism, queer liberation, animal liberation — all share a fundamental argument: we should grow our definition of who counts. Whose perspective matters? Whose suffering matters? All these movements ask us to expand our circle of care. Yet the concept of care itself is gendered as feminine in our cultural discourse, making arguments based on an ethic of care potentially threatening to masculine identity. This has consequences for the discussion of animal suffering and meat eating. In one study, psychologist Carolyn Semmelor divided 230 participants into two groups to observe reactions to learning more about a lamb dish. While one group received information about meat quality, nutrition and health, the other learned about the lambs' upbringing and slaughter. Women's perceptions of the lamb dish worsened after connecting it to the once-living animals. However, men's reactions varied, with some growing defensive and even doubling down on their “meat identity” by vowing to eat more meat.

A consequence of this is that women are more likely to be engaged in animal activism and more likely to be vegetarian or vegan than men — i.e. women are more likely to be convinced by the arguments of the No Meat future. Yet the connection between masculinity and meat goes far beyond the gendering of care or consideration of animal subjectivity. It has deep historical roots and is bound up in the history of colonialism.

We find recurring entanglements between masculinity and meat-eating again and again in the history of European literature. Men in ancient Greece got preferential shares of meat from, and special roles in, ritual slaughter throughout much of the year in Ancient Greece. In what we now know as the UK, male Anglo-Saxon slaves received more meat than female slaves. The ability to hunt and kill was seen as a symbol of the right to rule among French nobles in the court of Charlemagne. Even in Shakespeare, we see extensive symbolic connections between meat-eating and masculinity, where the shrew is tamed partly by being starved of meat.

These links are made on the backdrop of an even more consistent cultural pattern: the idea that meat is the food of the wealthy and powerful. This association was particularly strong in 19th-century Europe. To early nutritionists, meat was the ideal source of sustenance, flesh made food in order to make flesh anew. It was inevitable and right that it be the most valuable foodstuff and so, eaten by the wealthiest. Meat was the dish of power and the upper classes.

Accordingly, one reason you might want to emigrate to the colonies was the promise of greater space, freedom and wealth — partly in the form of regular meat-eating. Countries like the US, Argentina, and Australia achieved extremely high levels of popular meat consumption far earlier than European countries. Farming animals for meat in settler-colonial states was a key justifier of stealing land from Indigenous populations. Meat-eating also became a symbol of whiteness, an explanation for the success of European powers in dominating the world, a way of dividing other cultures into meat-eating “noble savages” (fetishized for their virility even while they were vilified for every other reason) and simply “backward tribes”.3

A Burger King ad for a beef sandwich.

They feel regressive, but most of these connotative links have survived into our culture today. We can see them expressed in anti-veganism, alt-right dietary discourse and fad diets like the carnivore diet. Online right-wing provocateurs dub their enemies “soyboys” in reference to racist-sexist ideas about non-meat consumption, Asian people and effeminacy; they use the slogan ‘Heil milk’ to invoke the claim that diet explains the domination of the world by colonial powers.4 In the largely male and very online world of fad diets, pseudoscientific claims come into contact with male supremacist conspiracy theories about exposure to estrogen through elements of modern lifestyles. The resulting discourse implores men to reclaim a ‘natural’ dominating masculinity by consuming more (or only) meat, through paleo or “carnivore” diets.5 Such examples may be extreme, but they are simply exaggerated versions of messages propagated through everyday advertising, entertainment and politics.

With all this context, it should be no surprise that different people have sharply differing intuitions on the ethics of killing and consuming animals and that gendered factors play into these viewpoints.6

Comments (0)