The UN Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Climate Change (‘COP’) has been getting steadily bigger over its almost 30-year history. Does size matter in the climate agenda, and how does the format of the conference further, or limit, its goal of international cooperation? This article considers the impact of expansion, and what it means for food systems.

Ruth attended COP28 as part of a role with another organisation, Sri Lanka-based think tank SLYCAN Trust. She also attended the 2022 COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh as an employee of the Scottish Government.

Food was finally and firmly on the agenda at COP28, the 28th annual UN climate conference of the parties held in Dubai in December of 2023. The UAE presidency, subject to much discussion about the suitability of a petrostate to host an event whose elusive and still controversial ambition has long been to phase out fossil fuels, on 1st December delivered the UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action, now with 159 nation signatories, a voluntary series of commitments including one to integrate food into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), national climate action plans which the Paris Agreement requires countries to establish and update every five years. COP28 was the first time the words ‘food systems’ have made it into the final decision text, with a reference included under the adaptation segment. These were two of six key breakthroughs identified on food at COP28, the others being:

-

Launch of Alliance of Champions for Food Systems Transformation, countries committed to a ‘whole government’ approach to food systems,

-

The release of Part 1 of the FAO’s Global Roadmap for Sustainable Food Systems,

- The non-state actor Call to Action on food systems, led by the UN High Level Champions,

- And an increase in finance for food system solutions.

[For impressions of some of the wider food conversations at COP, see Box 1].

Eating at COP

Food systems might have been a new feature in the official decision texts, but food has long been a big part of the small talk among COP attendees on the ground. The days are long, and staying energised in a space with scant food stalls, big crowds and a packed schedule has often been a challenge. Imagine, you have to find a sandwich for your minister, and ideally eat something yourself, when you have 20 minutes before your next event, it’s a 30 minute round trip to the nearest stall and the queue at lunchtime is a consistent 20 minute affair. Or you have to come up with a witty comment to distract your hungry audience when the catering for your reception, ordered through whatever portal the host country has set up, hasn’t arrived, because the over-burdened catering team are dealing with a few hundred event spaces over a thousand acres and some orders must inevitably go awry. ‘Hangry’ is a prevalent emotional state. Attendees, many of whom spend the 12 days constantly pressed for time, quickly learn where to find the shortest queues, which pavilions are offering free coffee (negotiators often work late into the night) and how strict is the policy on doggy bags at their hotel breakfast buffet. This was very much the reality at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, where catering arrangements were beset by problems and for some days attendees survived on ice cream and fizzy drinks. Coca Cola sponsorship at COP27 was met with fierce backlash, but trouble with water supplies meant Coke products were free for much of the conference to keep delegates hydrated. Which is why the tone of the queue chat in Dubai was one of pleasant surprise and appreciation: food stalls were plentiful and well spread out, the offerings were varied and healthy (or pleasingly unhealthy, such as the always well-attended middle eastern donut stall), and seemed to reflect a UAE commitment to align the food offer with 1.5 degrees – plant-based meats were much more plentiful than animal. The push for the conference to reflect and live up to its own internal conversations has been an ongoing campaign, and many celebrated this tangible on-site win.

|

Food messages at COP28 – impressions The Conference of the Parties is so huge, it is possible to experience many different versions. These impressions are only from my own experience:

|

Plenty of milestones, then, reached at COP28. Are they as significant as they seem? Last year’s COP27 saw the first mention of ‘food’ in a cover decision while the decision text, no doubt with Ukraine in view, included a first reference to ‘food security’. Sharm el-Sheikh also celebrated the first food pavilions – Dubai also hosted three, and saw food recognised as a theme on ‘Food, Agriculture and Water’ day (COP27 had ‘Adaptation and Agriculture’ day). Which begins to show the problem with the milestone method of evaluating COPs. Each COP foregrounds its novelty, the new commitments and the new calls to action. The milestone story is full of successes and never-befores; the far more cumbersome question of implementation is harder to track. This homework-checking was in part assigned to the Global Stocktake, a two-year process to take place every five years and begun at COP26 to ‘take stock’ of the implementation of the Paris Agreement and assess collective global progress; that process has struggled with detail, and you would be hard-pressed to pin down what the findings were from general COP coverage. It remains tricky for the observer to understand how much domestic policies have changed as a result of more ambitious NDCs, or how the ‘phase down’ of coal is being carried out in business and energy policy. Which is not to say that the milestones above are not objective successes, rather that COP achievements are measured by ambition; measurement of impact is diffuse and opaque.

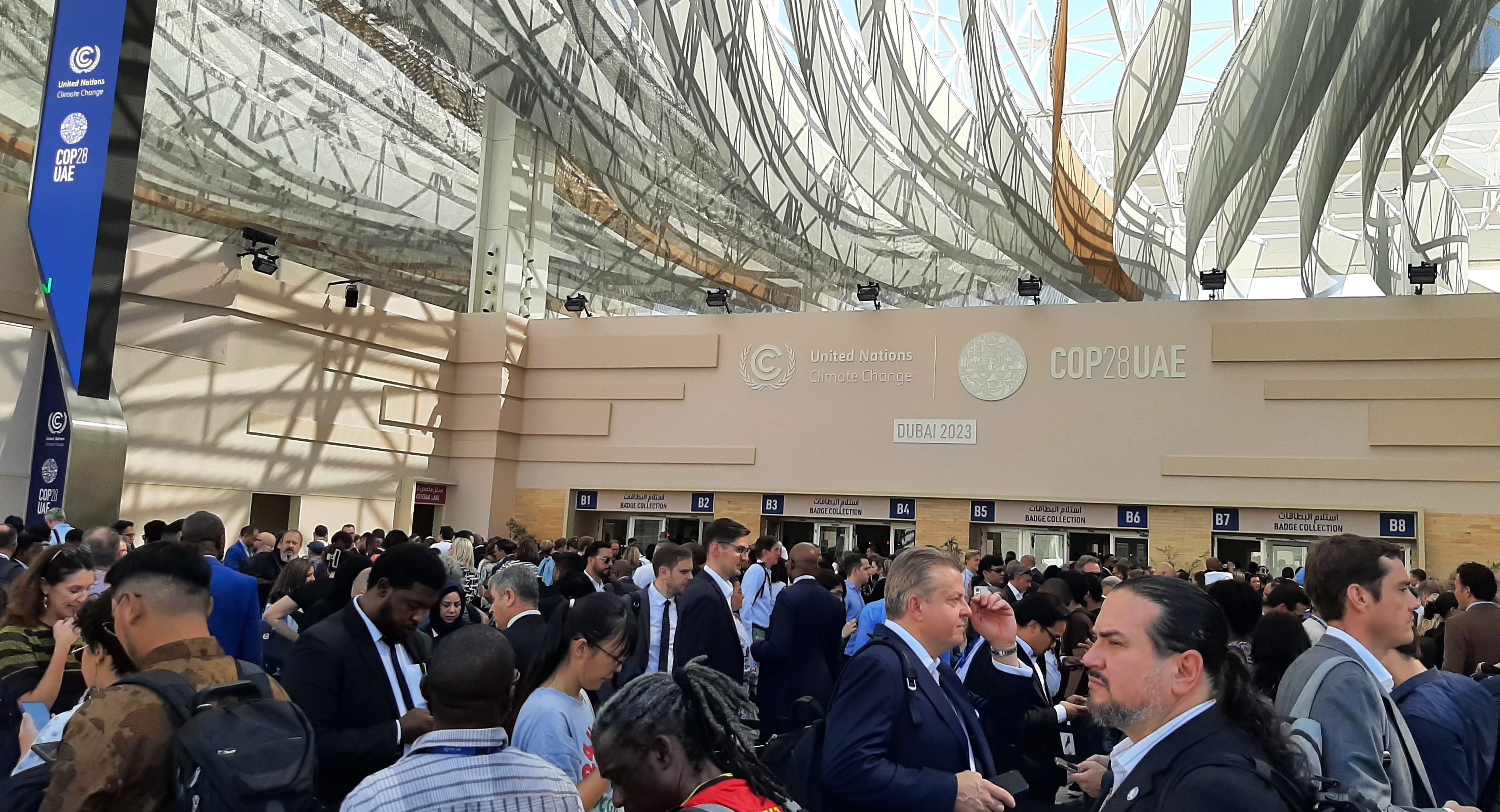

Delegates queue to collect their passes at the entrance to the Dubai Exhibition Centre. Photo courtesy of Ruth Mattock

Too big, and bigger than ever

This COP was, continuing a trend, the biggest on record, doubling the record already broken last year, and many times the original ~four thousand delegates of the first COP in Germany ‘95. Some of this is positive, reflecting growing interest in climate, particularly in the private sector. However, as UNDP chief Achim Steiner warned, such numbers make the challenge of hosting the conference, a huge feat of organisation and an enormous cost, available only to a smaller pool of nations – likely not those ranked among the most climate vulnerable. Increasing commercialisation seems a likely result. Sky News, who themselves sponsored 2021’s COP26, this year reported the million dollar sponsorship packages offered by the UAE at rates almost triple those offered in Egypt last year. Costs are passed down to member nations too, who fork out hundreds of thousands of dollars for pavilion spaces – an increase in Dubai on the already newsworthy figures quoted at COP26 seems plausible. It perhaps comes as no surprise that a caution appeared on the UNFCCC pavilion listing site: “It has come to the attention of the COP 28 Presidency and UNFCCC secretariat that some pavilion spaces in the Blue Zone are being further subleased or offered for co-hosting against fees. Those actions are not consistent with the purpose of pavilions in the Blue Zone and are not endorsed by the UNFCCC secretariat.”

There were inclusion achievements, with a significant youth presence in Dubai – but when the conference itself is growing, bigger numbers may not mean better representation. Participation from civil society is, and has generally been, unevenly spread across regions. In a remarkable victory for transparency – in response to criticism about previous oil and gas presence - 2023 saw the UNFCCC commit to publishing complete lists of attendees’ names, roles and affiliations (excepting technical staff). This has opened the door to some extensive analysis: the campaign Keep Big Polluters Out has grabbed headlines with their top findings, among them:

- “The 2456 fossil fuel lobbyists are only outnumbered by the 3081 people brought by Brazil (which is expected to host COP30), and the UAE, which as COP28 host brought 4409 people"

- “Fossil fuel lobbyists have received more passes to COP28 than all the delegates from the ten most climate vulnerable nations combined (1509), underscoring how industry presence is dwarfing that of those on the frontlines of the crisis.”

With the arrival of food on the agenda came scrutiny on the presence of ‘big ag’ and the meat lobby, which also increased. If total numbers continue to grow, industry presence is likely to do the same: corporations are better equipped to match this expansion than NGOs, community-focused bodies and even developing nations.

The UAE was expected to foreground business in its presidency, and for some the large finance and private sector presence evidences welcome attention on the climate agenda. The cost burden of mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage is well into the trillions, and governments and campaigners on all sides are looking for ways for the private sector to take on some financial weight. Others suspect rampant greenwash and suggest that only those corporations who are serious about their climate impact should attend (according, perhaps, to criteria set out by a UN Expert Group in 2022). On food, a focus on business privileges a particular angle, and encourages economic over rights-based rationales. While plenty of trade bodies are represented, there is a significant absence of farmer voices. If industry presence is to reflect the structure of the industry it purports to represent - which surely it should - smaller players should have a far greater presence. Farmer presence is important in a manner distinct from other production-level representation in the climate conversation such as coal, oil, gas, mining: food system transformation calls for change more than absences and hard stops – changes in agricultural practice as well as elsewhere in the supply chain. Farming in much of the world is a self-employed affair, making the raw material level of the chain an important locus for change.

That question of just who is attending the annual climate conference has long occupied COP-watchers. The list of on-site attendees, available to download from the UNFCCC here, has attracted novel analysis, such as this blog’s breakdown of Nigeria’s 1411-strong delegation, tied in 3rd largest with China. The blog compares the delegation as a percentage of total attendees to Nigeria’s proportion of world population and land area (in fact finding that Nigeria’s delegation is pretty proportionate). With a new transparency standard set, the food systems community has an opportunity to articulate who should be at COP and in what proportions.

Delegates on the main esplanade of Expo City in Dubai, the COP28 Blue Zone. Photo courtesy of Ruth Mattock

International cooperation and exchange – can the COP format deliver?

Dialogue takes different forms at COP in different spaces. Responsibility for the ‘Blue Zone’, which is only open to UNFCCC-accredited attendees, is split between the UNFCCC and the host nation, with negotiations and side events managed by the UNFCCC, and the pavilions and other Blue Zone meeting space managed by the host nation (the host nation also manages the unrestricted civil society and business led ‘Green Zone’). Attention, access and impact are not even across these spaces.

Negotiations

In the negotiation rooms, negotiators for all UN member nations attempt to carve out commitments, procedures and frameworks to guide and motivate climate action, concretising this in text that usually builds on work programmes that have run over the preceding years. Most of these sessions are open to those with Observer status - NGOs and IGOs admitted by the UNFCCC. Pre-empting difficulty with space, Dubai trialled a ticketing procedure allocating just one per observer organisation, but these didn’t guarantee entry to popular rooms and some saw party and overflow badges turned away (only those not negotiating) – another consequence of huge numbers. Negotiations on different work programmes (e.g. agriculture, technology, loss and damage) run concurrently so a party must bring sufficient negotiators if it is to have a say - or rely on its negotiating bloc, groups of nations formed on the basis of common interests. It is hard to tell how much of the almost 44,000 party and party overflow attendance was negotiators - only 194 of these use that word in the registration lists.

Side events

The nine Side Event rooms hosted 369 panel events in which organisers are encouraged to bring in as many organisations as possible (only one event per observer or nation is allowed). The idea is that these are on topics of relevance to the negotiating rooms: few mention those processes in more than a vague way and the likelihood of negotiators finding time to attend events at which they are not speaking is relatively slim. Audiences varied hugely – some events saw only a handful of the 200+ seats occupied, others (often those where industry were speaking, including one on working with farmers featuring agrochemicals trade association CropLife and another on animal-sourced nutrients featuring beef and dairy trade bodies) were packed and included journalists and planned interventions from ministers in the audience.

Pavilions

The Pavilions, operated by the host country on a commercial basis, are similarly variable. Most are taken on by nations or other UN bodies and multilaterals, others by coalitions with a thematic focus such as youth, oceans or climate and culture. There was no central timetable in Dubai (nor is there usually) for the schedules running across each of these 225 pavilions – some have a website, some appear on apps, some have a board outside their space. Once leased, the pavilions are a platform the nation or organisation can offer to the topics and people they choose – some are extremely competitive, with lengthy application processes to propose an event, others were still organising some sessions on-site. They usually feature meeting rooms, a space for exchange untracked by host or UNFCCC but from which significant progress can emerge in the form of bilateral agreements, partnerships and collaborations. There’s an element of status to having a pavilion, a very visible commitment to being part of the COP affair plus the freedom to channel conversations as desired. Each schedule is packed with presentations. How far the audience size delivers a return on the (significant) investment is questionable. National policy affairs, iterated in tens of versions across each nation’s pavilion, can struggle to attract the international audience. Some do better – the Barbados pavilion had a ready trickle of financial journalists and decision-makers in its finance-focused programme, thanks to their pioneering advocacy for reform of international finance architecture; other pavilions seemed to be filling seats entirely with their own nation’s delegation – something that’s easy to do with the huge numbers seen in Dubai. At an event entitled Commodities disrupted: finding the right balance between climate policies, global trade and achieving zero hunger at the ICC pavilion, seven or eight sat in the audience to hear big industry cheeses - CEO of Croplife Emily Rees, CSO of Cargill Pilar Cruz, CEO and DG of the International Fertilizer Association Alzbeta Klein - speak. What makes it worth it for these organisations? [For thoughts on why NGOs attend, see Box 2].

In the media, the commitment of world leaders to climate change is judged by presence or not at COP, and that measure is applied, or at least pre-empted, at the industry and organisation level too. It’s important to be seen, and seen to be doing. But with everyone on transmit-mode, the more vital efforts of listening and exchanging are deprioritised. With each nation or programme presenting in its own space, there is little opportunity for comparison of the policies that appear in the national climate strategies (NDCs) developed to achieve the commitments made in the negotiating rooms. Faced with such a huge timetable of options, people gravitate towards what they know and the proliferation of spaces (expanding alongside attendee numbers) reduces rather than encourages cross pollination. Nations and organisations need only ever appear in conversations over which they have significant control, and audiences are too often familiar as well as friendly. What is in theory an incredible international opportunity for challenge, evaluation and sharing best practice within a genuinely global gathering is instead taken up with show-and-tell.

|

What draws NGOs to COP? Theories of change Attending a COP is expensive, tiring and always open to accusations on the irony of flying round the world to address emissions. I spoke to a number of NGOs and academics about what it is they get from this often frustratingly slow-moving international engine, and the mechanisms for impact they rely upon. Some are closely tied to the UNFCCC process and the machinery of international government and multilaterals. Others simply take advantage of the space and people such an event provides:

|

‘Mend it, don’t end it’

The way to measure COP’s progress, according to Prof. David Victor, Univ. of California, speaking on a BBC podcast, is to compare where we are to where we would have been without it; we may not be on track to meet the Paris Agreement goals, but we are closer than we might have been. While progress in negotiations has been frustrated (and frustrating), as the COP has expanded progress has shifted into side spaces and the deals made that make up the host nation’s legacy, such as the UAE Declaration or the COP26 pledge to end deforestation. Outside of negotiations, progress need not depend on universal consensus and many fruitful collaborations emerge between groups of nations and multilaterals.

Conversations about reform are coalescing into specific demands. A recent op-ed under the banner of ‘mend it, don’t end it’ suggested the necessity for universal consensus upon which the COP proceeds should be abandoned in favour of a 75% majority, exposing the blockers and lining up financial penalties for obstructive actors. George Monbiot too has called for changing the consensus model. Prof. Adil Najam of Boston University says the problem is self-perpetuation - set a deadline of 2030, rather than always having the next COP as a back-up when agreement falters. The same commentator suggested the more ‘traditional’ method of confining negotiators until they reach agreement, rather than the current format that always runs beyond the scattering of hours allocated.

In the lead-up to Dubai there were calls for COP28 to rebuild trust in the model - greenwash and opacity are not in the service of trust, and it is often the staunch defenders of the process that have an analytical eye on its quality. Some want negotiation and the original concept of global commitment to emissions reduction to take centre stage again, and to strim out the growing ‘festival’ elements. Delegations could be encouraged and supported to prioritise negotiators. Side events could be more explicitly aligned to the negotiation strands, evaluating the success of past commitments and showcasing implementation. The UNFCCC could play a more active role in programming that prioritises knowledge exchange, using NDC commitments to connect good practice with capacity gaps. One straightforward improvement would be better communication on the ground through a central programme schedule.

Some of the most productive events I attended were open discussions, where leaders of organisations shared views and challenged each other, and where comment from the audience was invited and prioritised. TABLE is based on the belief that informed, honest and open-to-challenge dialogue is the foundation for good decision-making. It is not enough for this to be an intention or even a commitment, it must be built into the structure and space of the event. Without a change to the format, an opportunity for such dialogue at COP is being wasted.

Post a new comment »