Anke Brons is a PhD candidate at Aeres University of Applied Sciences Almere and the Environmental Policy Group, Wageningen University & Research. Her research focuses on questions of inclusiveness in relation to healthy and sustainable food practices.

Dr Sigrid Wertheim-Heck is associate professor global food system transformation in the Environmental Policy Group at WUR, and is professor Food and Healthy Living at Aeres University of Applied Sciences, both in The Netherlands. Her interest in urban food systems informs her agenda on the relationship between urbanisation, food provisioning and food consumption. She is part of TABLE’s board of directors.

This blog post is based on a Dutch essay, originally published in the Flevo Campus essay bundle ‘Veerkracht als opdracht’ (Resilience as a mission).

Image: Copernicus Sentinel-2, ESA, Flevopolder by Sentinel-2, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO. Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2018.

Introduction

Over the last year and a half, we have become collectively aware of the fragility of our food system. In the spring of 2020, Dutch supermarket shelves were regularly empty as a result of massive 'hoarding'1 . The well-oiled machine of our food supply was confronted with panic-stricken consumer behaviour, barriers to international trade and the shutdown of entire sectors, disrupting supply and demand. As if existing sustainability challenges were not serious enough, these disruptions also raised the question of whether our current food system is resilient enough to absorb shocks and continue to provide us with healthy, sustainable and safe food.

More and more Dutch cities are turning towards regional food supply chains, motivated by sustainability. COVID-19 has created an additional question for urban authorities: how can food systems be made resilient to unforeseen shocks at the same time as pursuing sustainability goals? Focusing on the “Support Your Locals” initiative in Almere, we explore the tension between national and international solidarity, between acute and longer-term needs, and between perspectives of the food system as a linear chain or as a complex, interlinked system.

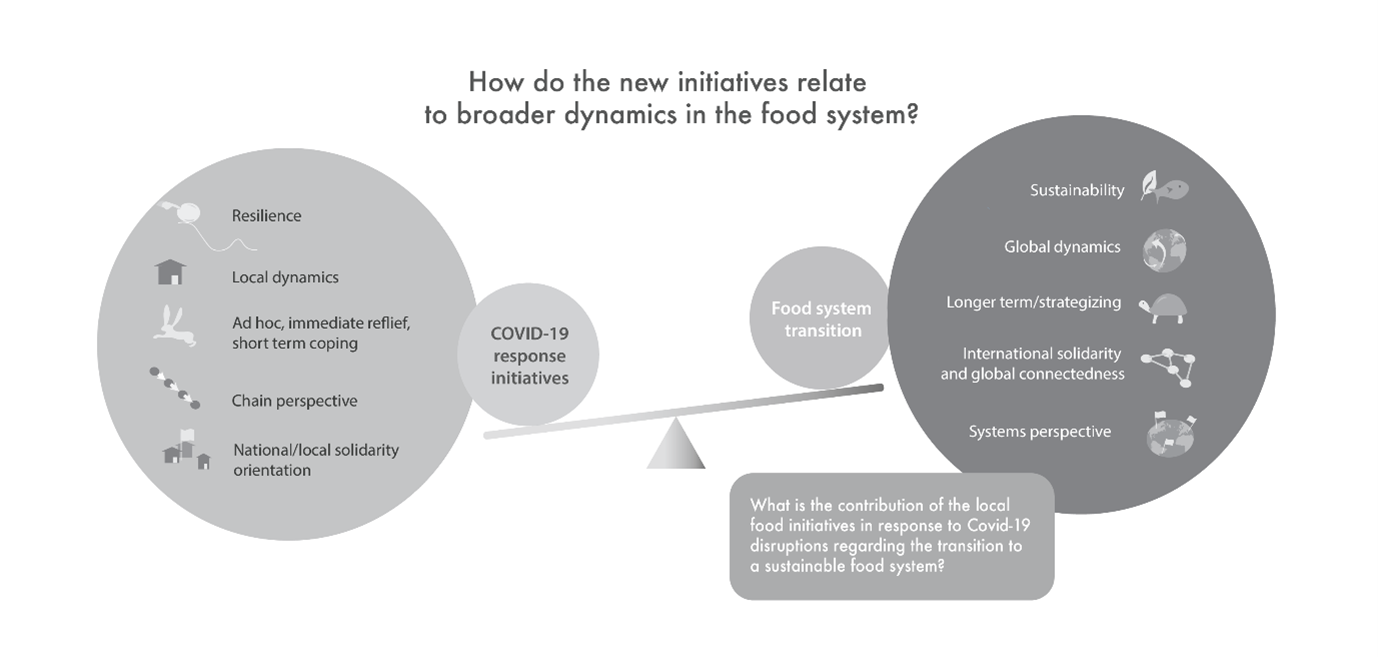

We conclude that, during the lockdown, resilience was about solving acute, tangible and specific problems in the chain, but that a sustainability transition requires a longer-term and systemic approach with an international perspective. The transition to sustainable and resilient urban food systems will benefit from diversity in the production/consumption chains, systems thinking, and international solidarity.

In this essay, we rely on different sources of information: scientific literature including our own research, as well as our own personal experiences around food during the lockdown, supported by news articles from around this time.

Balancing resilience and sustainability

There is some tension between resilience and sustainability, which are both recognised as vital elements of a future-proof food system. Sustainability, defined as meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the needs of future generations2 , is often interpreted as requiring minimal resource consumption. Food systems resilience is defined as the ability to cope with and recover from diverse and unforeseen disruptions in a way that ensures sufficient, adequate and accessible food for all3 .

Two common resilience strategies are surplus and diversity. In the example of internet access, a surplus strategy would require having more than one internet cable in case one fails, while a diversity strategy would imply having more than one way of connecting to the internet, such as a satellite connection in addition to a cable connection. Both resilience strategies might appear inefficient when viewed from a sustainability perspective, since they result in higher resource use.

The same tension between resilience and sustainability is evident within Dutch food systems, which are highly embedded in global supply chains. The average Dutch meal has travelled around 33,000 km before reaching consumers4 , and a common Dutch dish such as a sandwich with chocolate sprinkles uses several ingredients produced abroad, such as cocoa, soya and palm oil.

Consumers and policymakers increasingly view localised food production both as more resilient to shocks such as climate change and trade barriers and as more sustainable, through minimising transport. Although both advantages are disputable – for example, climate change is likely to increase Dutch crop failures due to dry periods5 and heavy rain6 , while transport only produces a small fraction of the carbon emissions of most food types7 – the trend towards localisation was emphasised during COVID-19. We saw acute shortages of medical protective equipment for 'our' care workers, such as face masks and gloves, leading to calls for greater control over resources within our national borders.

To illustrate how Dutch cities such as Almere are balancing their sustainability and resilience goals, we will look at how disruptions to the food supply caused by COVID-19 were handled in the Netherlands.

COVID-19 and the food supply

Preventing the COVID-19 virus from spreading required citizens to avoid social contact as much as possible. The drastic disruption of daily life changed every form of routine behaviour, including buying and eating food. Restaurants closed; people shopped less often to avoid exposing themselves to the virus in supermarkets; and waiting lists formed for online grocery deliveries. Product choice also changed, with people bulk-buying products with a long shelf life, such as tinned foods, pasta, and home baking products8 . This created unpredictability in supply and demand, which led to distribution problems.

Support Your Locals

As a result of the COVID-19 measures, a strong discrepancy emerged in the Netherlands in terms of food supply. While supermarkets could barely keep their shelves stocked because people started hoarding, many local food producers saw their markets vanish because of the forced closure of the catering industry. A range of initiatives emerged in response, drawing on the idea of solidarity between consumers and producers.

Amsterdam-based sausage makers Brandt&Levie joined forces with other local food producers to start an initiative called ‘Support Your Locals’, which offered food packages – or 'food boxes' – filled with local products. The movement spread across the country, with over 50 local initiatives joining the campaign. In Flevoland (Almere is in this region), the Flevofood Association, Local2Local and Studio Daagsch developed the so-called 'Flevourbox'. Meanwhile, the national ‘Benefrietjes’ campaign asked people to eat more French fries to avoid a surplus of potatoes – of a type used mainly by the catering industry – from going to waste after restaurants shut down.

Although Support Your Locals was born out of immediate necessity to prevent food waste and support struggling producers, it did not come out of the blue. There was fertile ground for such an initiative due to growing enthusiasm for the perceived social and environmental benefits of short supply chains in the Netherlands, supported by civil society initiatives such as the Taskforce Short Supply Chains (Taskforce Korte Ketens9 ).

Advocates of short supply chains argue that the physical and mental distance between farmer and citizen should be reduced to promote sustainability. An important assumption here is that citizens will be more willing to pay a ‘fair price’ for sustainably produced food and will be more willing to include (healthy) fresh products in their daily menu if they know more about food production and therefore have a better understanding of it. Though the sustainability contributions of short supply chains are disputed10 ,11 ,12 , many consumers believe that short supply chains are an important part of a more sustainable and healthier food system.

However, Support Your Locals does not necessarily contribute to more health and/or sustainability.

One example is the ‘Benefrietjes’ campaign, which aimed to reduce food waste, specifically potatoes, following reduced demand from restaurants during the lock-down. The campaign encouraged French fry consumption, which is questionable in the light of heath campaigns advocating healthy food consumption to reduce obesity which poses a risk of serious illness from COVID-19.

Image: matthiasboeckel, French Fries, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence

Another example is the ‘borrelbox’ – a box with drinks and snacks – which is also debateable in terms of its health and sustainability impact. While most of the Support Your Locals boxes contained a lot of fresh produce, the composition varied according to the participating food producers. For example, in Amsterdam a 'borrelbox' was available that contained mainly beers and sausages. Alcoholic beverages and processed meats are products that do not align with a planetary health diet13 and hence the perceived health and sustainability benefits of short supply chains.

It therefore appears that the Support Your Locals campaign was motivated partly by solidarity with local food entrepreneurs, as well as by health and environmental considerations. Indeed, the campaign appealed directly to solidarity with slogans like 'Buy local and support Dutch flavours!’ Support Your Locals became a national success, and at least in Flevoland it will most likely remain popular14 . The initiator Samuel Levie has been honoured as Food Hero of 2020 in the Food100 list of food changers, which lists 'leaders who work hard every day for a better and more sustainable food system'.

Solidarity

Support Your Locals appeals to a broader national consciousness, with a call to economically support 'our' (i.e. Dutch) farmers and food entrepreneurs. COVID-19 made us more aware of our national borders, when for example the border with Belgium was abruptly closed during the first lockdown.

It is understandable and important to support fellow citizens in times of crisis, which gives solidarity a strong national or even regional character. Yet, our current food system is essentially 'borderless'. Today’s global orientation of the Dutch food system was partly fuelled by the post-World War II aspiration that hunger should never be allowed to happen again. Stimulating exports became the central resilience strategy, based on the idea that if we can export food, we at least have enough for ourselves. This idea is embodied in the province of Flevoland, created on reclaimed land from the sea after WWII, which is dedicated to large-scale food production.

Image: Copernicus Sentinel-2, ESA, Flevopolder by Sentinel-2, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO. Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2018.

Besides, it is relevant to realise that agricultural, trade and environmental policies are largely determined at the European level. An example is the European Commission's Farm to Fork strategy that was published in 2020. It outlines a path towards 'a new and better balance between nature, food systems and biodiversity; to protect the health and wellbeing of our people while making the EU more competitive and resilient'. In short, while our current highly globalised food system clearly has many undesirable aspects – such as deforestation for palm oil and soy production – the solution does not simply lie in 'food nationalism'.

In addition, if we change something locally, we must also consider the influence of 'our' food system on the rest of the world and vice versa, as the Netherlands plays an important role in global food security15 . The recent call for a more 'internationalist' perspective16 is certainly relevant in a European context. For example, Dutch supermarkets have maintained relationships with farmers in Europe for decades, for example in Murcia, Spain. We should cherish these kinds of relationships, in addition to those with 'our' Dutch food producers, both because of European solidarity and because of long-term food security.

The desire for more local food must therefore go hand in hand with international solidarity. We must ask ourselves what we can produce close to home and which products need international chains. This also involves questions about what should be available in the supermarket year-round or in what cases we think the seasonal local supply is sufficient. The challenge is to coordinate changes in both local and international chains.

This challenge is also reflected in the composition of the Support Your Locals food boxes. The 'local' Flevourbox, for example, was also inspired by the multicultural composition of the population of Lelystad and Almere (cities in Flevoland). In accommodating the needs of the multi-ethnic population, it included some imported ingredients and enclosed inspirational recipes from various international cuisines14 . However, the demographic reach of Support Your Locals remains limited for the time being. Recent research of the Flevo Campus indicates that most consumers of the boxes in Amsterdam and Almere belong to higher income groups, have a high education level and have no migration background. This shows that the local food movement is still a niche.

In previous work we have shown that the cultural and socio-economic composition of many growing cities, including Almere, is very diverse, with a great variety of food habits and preferences17 ,18 . In a resilient and sustainable food system, solidarity also means having an eye for the diversity of urban consumers and their food habits and preferences. ‘Exotic’ recipes are not enough. Rather, it is about social inclusivity: sustainable and healthy food must be accessible to all and meet the diversity of tastes and preferences within the population. As a reminder, we recall the definition of resilience: 'sufficient, appropriate and accessible food for all'.

Sustainable resilience

This brings us back to the question of what a crisis like COVID-19 means for the transition to a more sustainable food system for cities. The pandemic stimulated an already shifting focus of cities towards a more locally oriented food system. With the shock of the lockdown, a great deal of creativity was released. A range of innovative strategies emerged to deal with the disruptions in our food supply. The common instrument of resilience was solidarity within the national borders, often primarily regional and urban, manifesting itself in support for 'our' farmers and 'our' entrepreneurs. The initiatives focused primarily on short-term 'acute resilience'. But what is their potential to also contribute to 'sustainable resilience' in the long run?

Image: Balancing local resilience and global sustainability. Design: Emily Liang.

The increased attention for and interest in local food and the importance of healthy eating are examples of much-needed and relevant impulses for the transition to a sustainable food system. The continued attention for Support Your Locals seems to indicate that certain shifts are actually being realized in the food domain. This is to a large extent thanks to 'our' food heroes, who are working towards more sustainable and shorter food supply chains. But however important and valuable this innovation is, a resilient and sustainable urban food system requires more and different considerations, for example when it comes to diversity in production/consumption chains, both for resilience and social inclusiveness. The promotion of national chains must also be weighed against international solidarity. Both considerations – diversity in production/consumption chains and an international perspective – are necessary for a resilient urban food supply and for making the transition to a future-proof, sustainable and inclusive food system.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made us aware that our food system is vulnerable and dependent. Resilience initiatives do not necessarily always serve the sustainability transition, and the solution for a sustainable future is not necessarily local. It is a balancing act to respond to unexpected disruptions and simultaneously work towards a transition to a sustainable urban food system. It is important to take a broad, systemic view of the transition to a truly sustainable, resilient food system for the benefit of all inhabitants of the city. The solution is not necessarily local, but short supply chains are an essential part of it.

What do you think? Leave a comment on TABLE's Community Platform.

Footnotes

- 1Lege schappen in de supermarkt door angst voor coronavirus’. Dagblad van het Noorden, 13 March 2020. ‘Retrieved from: https://dvhn.nl/groningen/Lege-schappen-in-de-supermarkt-door-angst-voor-coronavirus.-Dit-is-waarom-we-toegeven-aan-hamsterwoede-25457997.html

- 2Brundtland, G. (1987). Report Of The World Commission On Environment And Development: Our Common Future.

- 3Tendall, D. M., Joerin, J., Kopainsky, B., Edwards, P., Shreck, A., Le, Q. B., & Six, J. (2015), ‘Food system resilience: defining the concept.’ Global Food Security, 6, pp. 17-23.

- 4Rabobank (2017), ‘Metropool Regio Amsterdam krijgt voedselraad.’ https://www.rabobank.com/nl/raboworld/articles/food-council-commits-to-sustainable-food-for-amsterdam.html, 14 September 2017.

- 5Veraart, J. & Reidsma, P. (2019), ‘Effecten klimaatverandering op landbouw.’ Deltafact, STOWA-rapport.

- 6‘Minder spinazie in de schappen door onstuimig weer.’ https://nos.nl/artikel/2346739-minder-spinazie-in-de-schappen-door-onstuimig-weer.html, NOS, 4 september 2020.

- 7Ritchie (2020), You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local - Our World in Data.

- 8‘Rijst, knakworstjes, patat en wc-papier waren de toppers tijdens het hamsteren’, NOS, 29 March 2020. Retrieved from: https://nos.nl/artikel/2374539-rijst-knakworstjes-patat-en-wc-papier-waren-de-toppers-tijdens-het-hamsteren

- 9Task Force Korte Ketens is a civil society initiative and currently a foundation, which is supported by amongst other our Ministry of Agriculture.

- 10Born, B., and Purcell, M., (2006). Avoiding the local trap: scale and food systems in planning research. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 26, 195e207. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0739456X06291389

- 11Brunori, G., et al. (2016). Are local food chains more sustainable than global food chains? Considerations for assessment. Sustainability 8, 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050449

- 12Zwart, T.A. and Wertheim-Heck, S.C.O. (2021) Retailing local food through supermarkets: Cases from Belgium and the Netherlands. Journal of Cleaner porduction, 300, 126948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126948

- 13Eat Lancet (2019). The Planetary Health Diet. Retrieved from: https://eatforum.org/learn-and-discover/the-planetary-health-diet/

- 14 a b ‘Flevour box lijkt na corona een blijvertje te zijn.’ FlevoPost, p. 19, 2 September 2020.

- 15Oosterveer, P. & Wertheim-Heck, S. (2020), ‘Nederlands voedselbeleid in globaal perspectief’ In: I. de Zwarte & J. Candel (red.) Tien miljard monden. Hoe we de wereld gaan voeden in 2050. Prometheus, Amsterdam.

- 16Candel, J. (2020), ‘Oproep tot een internationalistisch landbouwdebat.’ Column op www.foodlog.nl, 27 augustus 2020: https://www.foodlog.nl/artikel/oproep-tot-een-internationalistisch-landbouwdebat/

- 17Brons, A., Oosterveer, P., & Wertheim-Heck, S. (2020), ‘Feeding the melting pot: Inclusive strategies for the multi-ethnic city.’ Agriculture and Human Values, 37, 1027–1040.

- 18Wertheim-Heck, S. & Lanjouw, J. (2018), ‘Wat eten we vandaag? Een pleidooi voor de menselijke maat in voedselsystemen.’ In: J. Lohman (red.) De buik van de stad. Toekomstperspectieven op voedsel, stad en land. Van Gennep, Amsterdam.

Post a new comment »