During World War II, the British government transformed the domestic food system, implementing laws to cut food imports, encourage citizens to grow more of their own food, reduce food waste, and ration scarce foods such as meats, butter and sugar. In this blog post, educator and food writer Eleanor Boyle draws out the lessons that this historical case study offers for transforming today’s food systems in the face of the environmental crisis. She argues for reducing food waste, introducing modern versions of “British Restaurants” to offer low-cost meals and, controversially, rationing some foods including beef and dairy.

About the author: Eleanor Boyle is an educator and writer in Vancouver, Canada. Formerly a journalist and college instructor, she holds a BSc in behavioural science, a PhD in neuroscience, and more recently, an MSc in food policy from City University London, working with Professors Tim Lang, David Barling, and Martin Caraher. Her publications include High Steaks: Why and How to Eat Less Meat (New Society 2012) and Mobilize Food! Wartime Inspiration for Environmental Victory Today (FriesenPress 2022). Eleanor has deep ties to Britain through family, study, and travel.

Crisis and resilience

Wartime food has been on my mind since I first learned about Britain’s World War II Ministry of Food, and the nation’s transformation of agriculture and diets in hopes that domestic food security would help win the war. So I’ve been researching this historical initiative to make British food resilient in crisis—including its strategic objectives of less dependence on imported foods, more homegrown food for people and less feed for livestock, and absolutely minimal food waste.

I’ve come to believe that this case study has lessons for today, as I outline in my book, Mobilize Food! Wartime Inspiration for Environmental Victory Today.[1] We have a climate emergency, pandemics, serious inequality, and global conflicts, plus health and social reasons that food systems need a reboot. While our aim is not to win a military victory, food goals today do include: less dependence on uncertain imports; more plant-based and less livestock-based agriculture and diets; and much less food waste. Maybe we could take cues from the past.

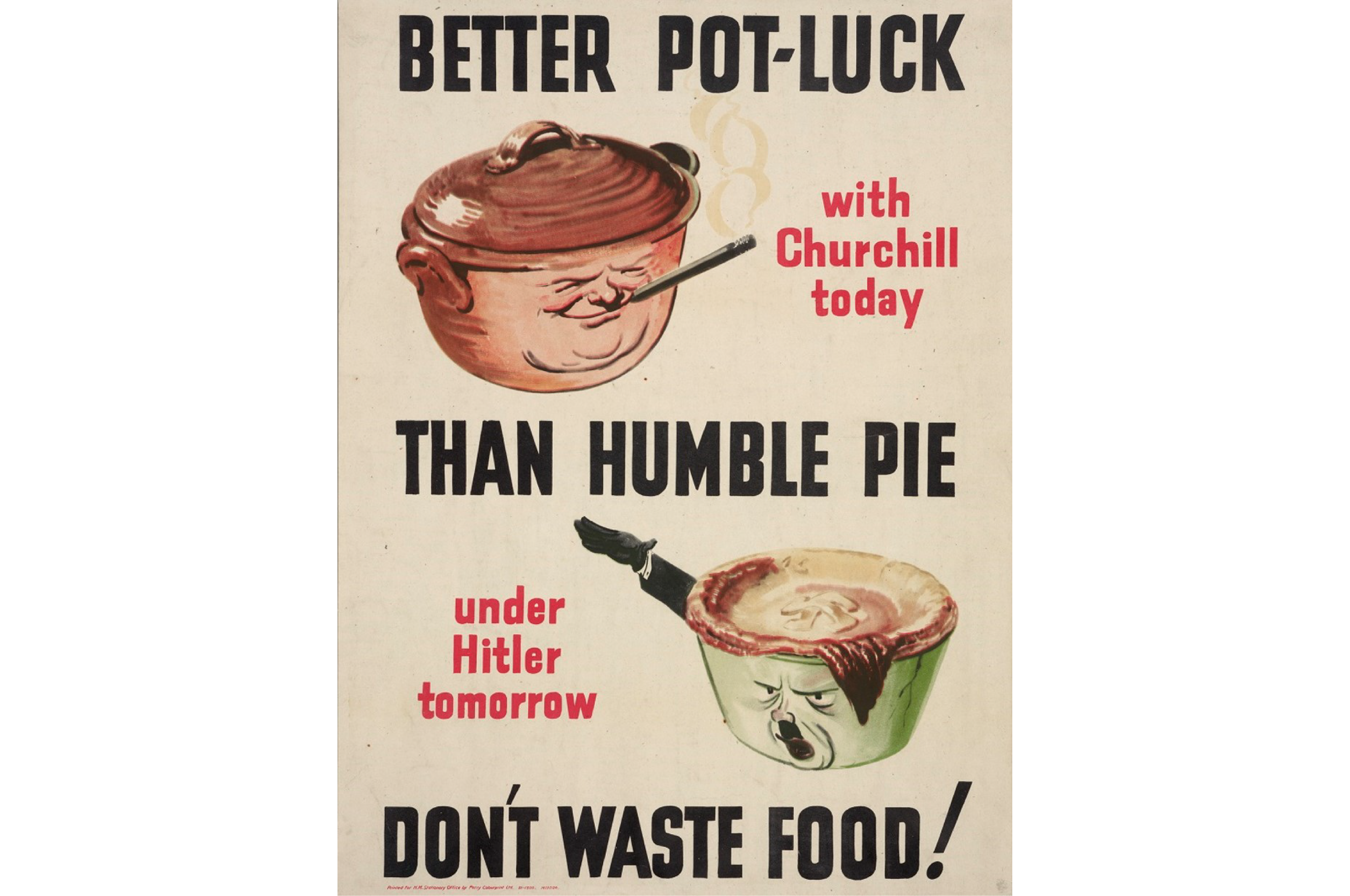

Image: War poster. Permission for non-commercial use courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

The food programmes: You can’t win a war if you’re hungry

In the 1930s, as war appeared imminent, British preparations needed to include food. The Conservative government was not prone to involvement in markets, but remembered British hunger during the First World War, and knew that conflict wrecks food systems, as we now see in Ukraine, Yemen, and beyond. So leaders assumed responsibility for food and implemented laws and regulations to:

- Cut food imports, because ships would be vulnerable to attack;

- Plough up farm pastures and plant more human-edible crops;

- Encourage citizens to grow and raise more of their own food;

- Reduce food waste through education and legal sanctions;

- Implement rationing of scarce foods such as meats, butter, sugar, and some imports, aiming to give everyone a fair share;

- Ensure availability of adequate calories and nutrients via price controls, school food, and publicly run British Restaurants; and

- Address farm labour shortages through voluntary schemes such as a Women’s Land Army, holiday farm camps, and more.

Leadership was essential

Citizens would need information and motivation. So the government revived a Ministry of Food, and found a capable and personable Minister, known by his title Lord Woolton. Determined to increase the profile of food as an element in victory, Woolton spoke often on the wireless encouraging people to embrace simple meals, respect ration rules, and persevere. The aim was to impart a sense of urgency and inspire a culture of pride, so citizens felt like home-front warriors. This came through in interviews I conducted with elders who were children there:[2]

A lot of people dug up their beautiful front-yard flower gardens to plant vegetables… You’d see all the neighbours out digging at 11 p.m. — Pat Marshall

[Harvesting] was hard work, but we were so proud that we were helping to save our country from starvation. — Helen Melville Smith

It was Lord Woolton's diet that we had all through the war. He was made a Lord, but as I’ve always said, he could have been beatified. — Olwyn (Wynne Finch) Wake

Leaders emerged at all levels to educate and assist. Ministry home economist Marguerite Patten became a celebrity educator/chef with demonstrations of healthy cookery on rations. Comic duo Gert and Daisy, popular on BBC radio, guided listeners through new food rules and cracked jokes about making banana cream pie with no bananas and no cream. In towns, communities, and farms, neighbours organised clubs to cooperatively raise pigs and other small livestock, and shared tips on catching wild rabbits or growing greens. Creative posters in shops, factories, and pubs invited families to Dig for Victory, and fictional characters Doctor Carrot and Potato Pete promoted healthy eating for children, including (in the absence of ice cream) the wartime treat ‘carrot on a stick.’

Image: War poster. Permission for non-commercial use courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Results: Objectives met, mistakes made, the power of food policy evident

It was a journey with bumps along the way. But historical data and analyses provide evidence that the British wartime food programmes:

- Shifted farming toward local production;

- Cut food waste significantly;

- Fed the domestic population adequately—for millions, better than before the war;

- Contributed to narrowing the inequality gap between rich and poor;

- Helped improve population health, especially for children; and

- Revitalised domestic agriculture for the war and beyond.

The programmes met the population’s wartime needs for calories and nutrients. Health analysts of the time, and later historians, concluded that many who had been undernourished or malnourished before the war [3] were now better fed. “The average diet of all classes was better balanced than ever before,” reported the nation’s chief medical officer in 1946.[4, p. 115] The poorest one-third of the population had more access to protein, vitamins, and calcium than before the war, reported historian Lizzie Collingham, adding that full employment and fair distribution of food through rationing “had a revolutionary impact on the nation’s health.”[5, p. 394]

Meals were often dull, without the usual amounts of meat, fats, sugar, eggs, and fruit. Some eaters longed for another helping at tea and grumbled about the monotony. But it was mostly the rich who saw a decline in their meal satisfaction [5, 11].

Health statistics surprised many, after prewar predictions that fewer calories, less meat, and less variety would make people sick. By numerous metrics, Britons became healthier. That 1946 national medical report called wartime health “phenomenally good,” adding that: “an outstanding feature has been the low mortality of children from disease.”[4, p. A3] Death rates fell for women in childbirth, for infants and for children. Adults showed lowered mortality from tuberculosis and pneumonia, and levels of diabetes declined.[4] Historians agree that food played a central role.

That's not to say the food programmes unfolded smoothly. There were conflicting priorities, controversies, and mistakes. The most serious was in 1943, when the Indian province of Bengal suffered serious food shortages. A combination of mismanagement, minimisation by London of the potential disaster, and a refusal of Churchill's war cabinet to send food resulted in the deaths by starvation of roughly three million people. Many factors were at play, but historians have concluded that Britain played an active role in exacerbating or even causing the famine, by refusing to divert food from the war effort toward starving Indian citizens, and by prioritising the feeding of its home population.[5,6,7]

It was an indelible moral stain on Britain. Yet many of the domestic measures taken within Britain fed and rallied citizens for the duration, and so helped win the war.

How relevant is this for our time?

Today we face an emergency more serious than a pandemic. "The climate emergency is our third world war," declared Nobel economist Joseph Stiglitz in 2019. "Our lives and civilisation as we know it are at stake, just as they were in the Second World War."[8]

Food systems contribute to the problem. As we produce and consume it today, food is responsible for at least one-quarter and possibly one-third of human greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs)—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.[9] Factors include destruction of forests and wetlands; factory-farming of livestock; excessive use of fertilisers and chemicals; and concentrated food-sector ownership that relies on fossil-fuel-based global trade. Agribusiness also often pollutes local ecosystems, consolidates land away from small and indigenous farmers, and rears livestock in crowded conditions that increase the likelihood of pandemics.

Food can therefore be part of environmental solutions. We see from wartime Britain that food systems can change, and may not be as entrenched as we fear. Given compelling reasons and specific strategies, people can co-operate and change how they eat and how they act.

In my view, we also see the power of public leadership. In light of wartime evidence, I suggest that a segment of national food systems be controlled and managed by government rather than private enterprise. Aims would be not profit but the public good, including sustainable agriculture and universal access to healthy and culturally appropriate food. Specific elements of such a system could include modern versions of low-cost British Restaurants; mandatory measures to lower food waste; and rationing systems for foods such as beef and milk that have disproportionate climate impacts. As with any social programmes they could recognise diverse needs and accommodate exceptions. Leadership would need to be bold and involve civil society, citizens of diverse experiences, and some business, while ensuring that priorities were environmental and social.

Image: War poster. Permission for non-commercial use courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Could food transformation even be possible today?

Some will say it can’t be done. They’ll argue that:

(1) 'Social cohesion was probably greater in the 1930s/40s. Today, many would refuse to cooperate, as we've seen with Covid rules.' Yet pre-war Western societies were not cohesive, but had massive income inequalities [10, p. 102] and economic resentments. Nor was Britain, at the start of the war, a particularly compliant society. When rationing was announced, many were sceptical or angry. But after implementation and public outreach, surveys showed considerable support—not universal, but widespread. In November 1939, 60% of respondents said they wanted food rationing. By 1942, two polls showed that 75% to 90% of women (who managed the households) approved of rationing, and that many hoped it would continue postwar.[11,12]

(2) 'Citizens habituated to unfettered consumption would not agree to limitations.' Having argued for rationing of emissions-intensive consumption (e.g. flying, driving, and meat-eating) I know the topic ignites passionate debate.[13] Yet climate-related disasters could justify an evidence-based allocation system, allow us to consume without uncertainty or guilt, and ease our climate anxiety. Besides, rationing (though with less controversial terminology!) of consumer goods is commonplace—usually by price.

(3) 'We don’t need to ration meat because there’s no shortage.' Yes, it’s true that food markets are replete with meat. But in gravely short supply is our planet’s capacity to produce current and projected amounts of animal-source foods sustainably, and our atmosphere’s capacity to absorb the GHGs.

I began by suggesting that wartime food offers lessons that remain relevant even in today’s very different health and social context, and will wrap up with a striking bit of evidence. Though environment was not on the radar screen for wartime food architects, ultimately, crisis-ready World War II British diets were:

- more local,

- more seasonal,

- more plant-based,

- less processed, and

- less wasteful.

Sounds to me like a science-based prescription for sustainable and healthy diets.

What do you think? Leave a comment at the bottom of this page, or join the discussion on the TABLE community platform here: Should we ration high-carbon foods?

References

- Boyle, E. Mobilize Food! Wartime Inspiration for Environmental Victory Today. Victoria, B.C.: FriesenPress, 2022.

- Interviews I conducted with elders: https://www.eleanorboyle.com/wartime-memories.

- Boyd-Orr, John. Food, Health and Income: Report on a Survey of Adequacy of Diet in Relation to Income. London: MacMillan, 1936.

- UK Ministry of Health / Chief Medical Officer Wilson Jameson. On the State of the Public Health During Six Years of War—Report of the Chief Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health, 1939–1945. London, 1946.

- Collingham, Lizzie. The Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food. New York: Penguin, 2011.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. “‘Sufficiency and sufficiency and sufficiency’: Revisiting the Bengal Famine of 1943–44.” UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series WP10/21, University College Dublin, Ireland, June 2010. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1664571.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. Famine: A Short History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. “Climate Change is Our Third World War. It Needs a Bold Response.” The Guardian, June 4, 2019. https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jun/04/climate-change-world-war-iii-green-new-deal.

- Ritchie, Hannah. “How Much of Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Come From Food?” Our World in Data (blog), March 18, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions-food.

- Klein, Seth. A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency. Toronto: ECW Press, 2020.

- Mackay, Robert. Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain During the Second World War. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2002.

- Calder, Angus. The People’s War: Britain 1939–1945. London: Jonathan Cape, 1969.

- Boyle, Eleanor. “The Climate Crisis is like a World War. So Let’s Talk About Rationing.” Globe and Mail: December 14, 2019. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-climate-crisis-is-like-a-world-war-so-lets-talk-about-rationing/

Further Reading

Evans, Bryce. Feeding the People in Wartime Britain. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

Garnett, Tara. “Plating up Solutions: Can Eating Patterns be both Healthier and More Sustainable?” Science 353, no. 6305, (2016), 1202-04. DOI: 10.1126/science.aah4765

Lang, Tim. Feeding Britain: Our Food Problems and What to Do About Them. London: Pelican, 2021.

Mackay, Robert. Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War. UK: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Roodhouse, Mark. Black Market Britain 1939-1955. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Short, Brian, Charles Watkins, and John Martin, eds. The Front Line of Freedom: British Farming in the Second World War. Exeter, UK: British Agricultural History Society, 2007.

Comments (0)