Programs aiming to drive change within smallholder agri-food systems commonly involve training initiatives with a limited number of selected "model farmers" who then pass on the knowledge they have learned to the wider smallholder community. These model farmers are often chosen as they are seen to be opinion leaders, central individuals within social networks, who are presumed to have greater success in influencing people's behaviour and so driving change. Using data from an experiment implemented among Indonesian cocoa farmers, this study set out to determine whether this assumption is indeed the case.

Specifically, 18 opinion leaders (identified via interviews and social network surveys of 1,885 cocoa farmers) and 18 randomly selected individuals were chosen as model farmers for a scheme promoting the benefits of pruning on cocoa tree health and yield.

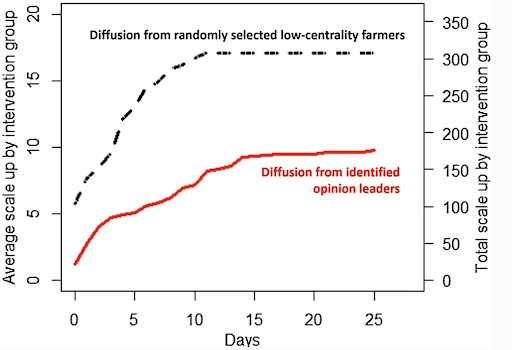

In direct contrast to expectations, the randomly selected farmers convinced almost twice as many of their peers to take part in the initiative compared to the highly socially central opinion leaders (see image below). Moreover, whilst the majority of identified opinion leaders were senior men, women were better at promoting the scheme, even when they were not identified as central to local social networks of agricultural advice.

Image: Figure 3, Matous, 2023. Cumulative diffusion curves of the impact of the intervention on farmers taking the recommended action. The vertical axis shows the number of the farmers to whom the intervention has diffused through social networks and the horizontal axis shows the number of days since the start of the intervention

These findings may reflect a bias in conventional network surveys used to select model farmers which may lead to ineffective spread of an intervention. For example, women and young farmers may access informal networks not recognised by the broad community, intervention organisers or researchers. The paper cites other research finding that women often have stronger information connectivity via close-knit networks with family and friends that will be missed by conventional district wide sociometric surveys despite them being potentially better model farmers. Moreover, other research finds that people identified as opinion leaders by their peers may simply be chosen based on perceived social status rather than any real influence on actions and practices. Overall, effective interventions must consider wider social norms, traditions, cultural stereotypes and biases, along with including underrepresented groups (e.g., women), to achieve radical success and avoid the potentially limited impact of conventionally selected opinion leaders.

Another issue with selecting model farmers by focusing on highly socially central opinion leaders is equity. Exclusively selecting farmers with high social status and privilege (who are often senior men) for priority access to novel technologies and resources is ethically questionable. However, the authors do not entirely rule out working with individuals with high social status. First, even if less effective, their impact is more predictable (there was significantly more variation in the random group). Second they have a large impact over status quo so convincing them the scheme is worthwhile is a necessary endeavour.

Overall, this study highlights the need to avoid (often gendered) biases in selecting opinion leaders and to ensure that underrepresented groups (particularly women) that truly represent the target community are included as model farmers. This can make initiatives aiming to achieve change within smallholder agri-food systems both more equitable and more effective.

Paper abstract

Social networks can influence people’s behaviour and therefore it is assumed that central individuals in social networks, also called “opinion leaders”, play a key role in driving change in agricultural and food systems. I analyse the outcomes of an intervention (that encouraged Sulawesi smallholder farmers to take a specific action toward improving the health of their cocoa trees) to assess the impact of engaging opinion leaders in agricultural programs that aim to change farmers’ practices. The intervention has been implemented through (a) 18 opinion leaders identified by interviews and a social network survey of 1885 cocoa farmers; and (b) 18 randomly selected farmers who were not central in local social networks. The obtained social networks and statistical data were quantitatively analysed and the results were interpreted with input from the field staff. Contrary to expectations, the highly socially central opinion leaders were not more effective in promoting the initiative in their communities. On average, randomly selected low-centrality farmers convinced almost twice as many of their peers to take the recommended action as compared to the identified opinion leaders (17.1 versus 8.6) but the variation within the random group was also significantly higher. Importantly, while the identified opinion leaders were mostly senior men, women performed better in influencing others into taking action even when their centrality in local social networks of agricultural advice was lower. I discuss the implications of the conventional selection of perceived opinion leaders as model farmers for achieving sustainable and equitable change at scale in agriculture and propose practical alternatives.

Reference

Matous, P., 2023. Male and stale? Questioning the role of “opinion leaders” in agricultural programs. Agriculture and Human Values, pp.1-16.

Read the full paper here. See also the TABLE Research Library item Gender equality in climate-smart agriculture.

Post a new comment »