The narrative that individuals are responsible for their food choices and dietary health forms a large part of political and media messaging. This report demonstrates that behaviour is in fact influenced by a wide array of factors that are out of the consumer’s control and that effective policies to improve dietary health need to go further than nutrition and cooking education and public health campaigns.

Summary

Over the past 30 years in England, 14 Government strategies and nearly 700 policies have attempted to reduce levels of obesity and failed. These policies have focused mostly on individual behaviour change and have been non-interventionist. One example, the 5-a-day campaign, illustrates this education-behaviour gap. The message has been communicated widely for over thirty years, with up to 85% of individuals aware of the message, yet the average intake of fruit and vegetables has remained stagnant, with only 33% of adults and 12% of children meeting the targets. Equally, suggestions that low-income groups, who are at higher risk of food poverty and obesity, could improve their diets by learning to cook are inaccurate. Lower income groups are in fact more likely to cook at least once a day than higher income groups, but the number of meals cooked at home overall is low across all groups in the UK. Time availability in the UK is low, with 75% of the UK citizens (aged 16-65) in employment compared to 66% average in Europe according to the OECD. On a scale from 1-10, the OECD scored work-life balance in the UK at 5.6 compared with 8.0 in Germany and 9.4 in Italy. Thus cooking and nutrition education programmes have also been ineffective at treating the root cause of unhealthy diets. Their implementation through school cooking lessons has also been disparately distributed with 50% of primary schools receiving 10 hours or fewer, but 10% receiving over 30 hours of tuition.

Another example of behaviour change interventions that fail to produce results is food labelling. Food labelling is often used as an educational tool to provide consumers with point-of-purchase information to enable them to make informed decisions. However, research has demonstrated that consumers are more likely to use traffic light labelling systems to avoid bad foods rather than to choose healthy options; consumers are more focused on the transition from red to amber, with little regard for the transition from amber to green. In fact, mandatory labelling is more effective at incentivising reformulation in the food industry, with evidence submitted by Sainsbury and Asda to the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee in 2011 indicating that traffic light labelling stimulated reformulation of product health profiles.

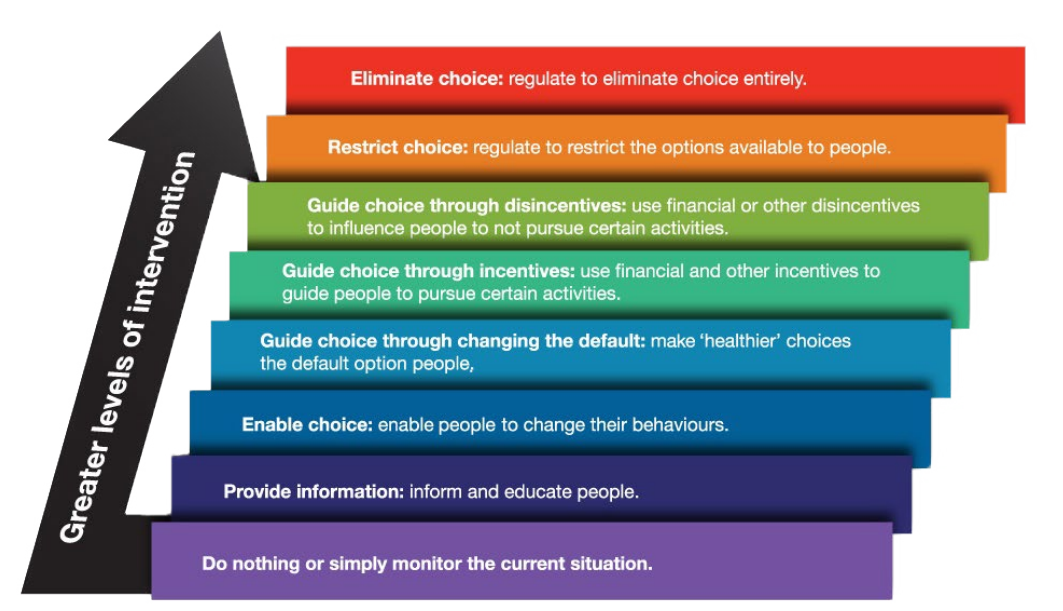

The focus on personal responsibility and blame is most prevalent in the politics and public narratives surrounding obesity. However, the increase in average BMI in industrialised countries has happened so rapidly that a sudden collapse in willpower is not a plausible explanation. Since 1980, it is estimated that the prevalence of obesity in England has risen from 6% in men and 9% in women to 27% in men and 29% in women. A more likely explanation is the profound shift in the global food system and local food environment, as well as the creation of heavily processed foods. Nearly 700 policies have attempted to reduce levels of obesity; however most of these policies focused on relying on individuals to change their behaviour, rather than addressing the wider structural drivers of obesity and poor diet. If governments wish to be more effective, they need to focus on interventions which aim to change the environment and introduce mandatory, rather than voluntary, regulations. The Nuffield Intervention Ladder shown below ranks possible policies by increasing levels of intervention from the most interventionist (ones that work to change the environment by restricting and changing choice) to least interventionist (reliant on education and information provision).

Fig.1 Nuffield incentive ladder showing policies ranked from highest to lowest levels of interventionism.

The second figure below shows misconceptions about the effectiveness of various policy interventions in the mind of the public, based on a systematic review. The graph demonstrates that the public has internalised the message that obesity is a case of individual responsibility and lack of willpower, and that the most effective means of tackling obesity is through education and enabling choice.

Fig. 2 The misconceptions around the effectiveness of obesity policies.

In order for policies designed to improve dietary health to be successful, they need to change the social and commercial environment people live in in a sustained and coordinated way. There are three main factors that are needed for any given behaviour change to occur: capability, opportunity and motivation. The food environment is important here because it is the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural contexts in which people engage with the food system. The most common food environment is the physical high street and the supermarkets that consumers purchase food from, as well as the foods that are made available, accessible, affordable and appealing to them. Policies and interventions to change the food environment therefore focus on the structural determinants of healthy diets and therefore provide both the capability and the opportunities for people to engage with health-promoting behaviours. The current food environment makes less healthy foods the more available, affordable and appealing options:

- Affordability - more healthy foods are over twice as expensive per calorie as less healthy foods.

- Availability - 1 in 4 places to buy food are fast-food outlets. Moreover, in the most deprived fifth of local authorities, 31% of places to buy food are defined as fast-food outlets

- Appeal - A third of food and soft drink advertising spend goes towards confectionery, snacks, desserts and soft drinks compared to just 1% for fruit and vegetables

What is needed instead is action from policymakers across the food system in order to transform food environments. The necessary shifts to healthy diets can only be achieved through incentives and standards in the system within which businesses operate. Shifting these incentives is the role of the UK Government. The authors elaborate on a case study in Finland to demonstrate a food system approach to improving population health:

- In 2009, 20% of 5-year-olds in Seinäjoki, Finland, were living with overweight or obesity.

- HFSS snacks were removed from childcare centres

- Schools started serving healthier meals

- Annual health checks were implemented in schools

- Finland’s Health Care Act now requires cities to make sure that health is incorporated throughout their decision-making

- All students receive free and healthy lunches, in line with the Finnish National Nutrition Council dietary guidelines.

- HFSS foods are taxed at higher rates, and Finland has recommended reducing the availability of HFSS food and drink in school vending machines, as well as limiting how such foods can be marketed for children.

- Schools also have to provide mandatory nutrition, cooking, health and physical education lessons

- By 2015, the prevalence of overweight or obesity among 5-year-olds in Seinäjoki had dropped to 10%.

Find the report here and more on sustainable healthy diets here

Post a new comment »