1. The workshop

This is an exciting moment for economic and political ideas. The challenges of the climate and biodiversity crises have generated a wealth of new thinking and of old ideas made new. Across the political and economic spectrums, the agenda for the future economic organisation of human societies has opened up with new possibilities, with different actors advocating for different pathways. While free-market thinking and a capitalist, profit-driven, growth economy remain the norm, some committed to this perspective recognize the need to adapt and transform. Others question the idea that economic growth is inherently good for human societies, and argue that approaches such as degrowth, post-growth, or steady-state economic thinking are necessary to align human societies with the limits of the Earth’s ecosystems. Cutting across these positions are those who argue for more robust values-led or mission-led governance and associated policies. At the same time, traditional political divides between left and right have blurred, leaving less certainty about political futures but allowing more opportunities for change. Investors, philanthropic organisations, and research funders support projects which align with their ideologies and associated theories of change, shaping avenues for transformation.

Yet, in most of these imaginative future-oriented political discussions, there is a striking element missing: a concerted attention to the food system, from production through to processing, distribution, and consumption. This is an oversight that needs addressing. Food provisioning is a basic aspect of human flourishing and survival, and is deeply implicated in the challenges of living within planetary boundaries. Food systems are the primary drivers of biodiversity loss, the contributors of up to a third of greenhouse gas emissions, and the sources of nitrogen and phosphorus loading in the earth’s biogeochemical cycles. While many food systems thinkers are already exploring pathways for a better food future, they too are constrained by the boundaries of their disciplinary expertise. There is a need for strengthened connections between those working for change in the food system and those thinking about new economic and political futures.

The work described here represents a small first step in making these connections. This first section describes our purpose and goals behind this workshop and the methodology we used to develop and facilitate it.

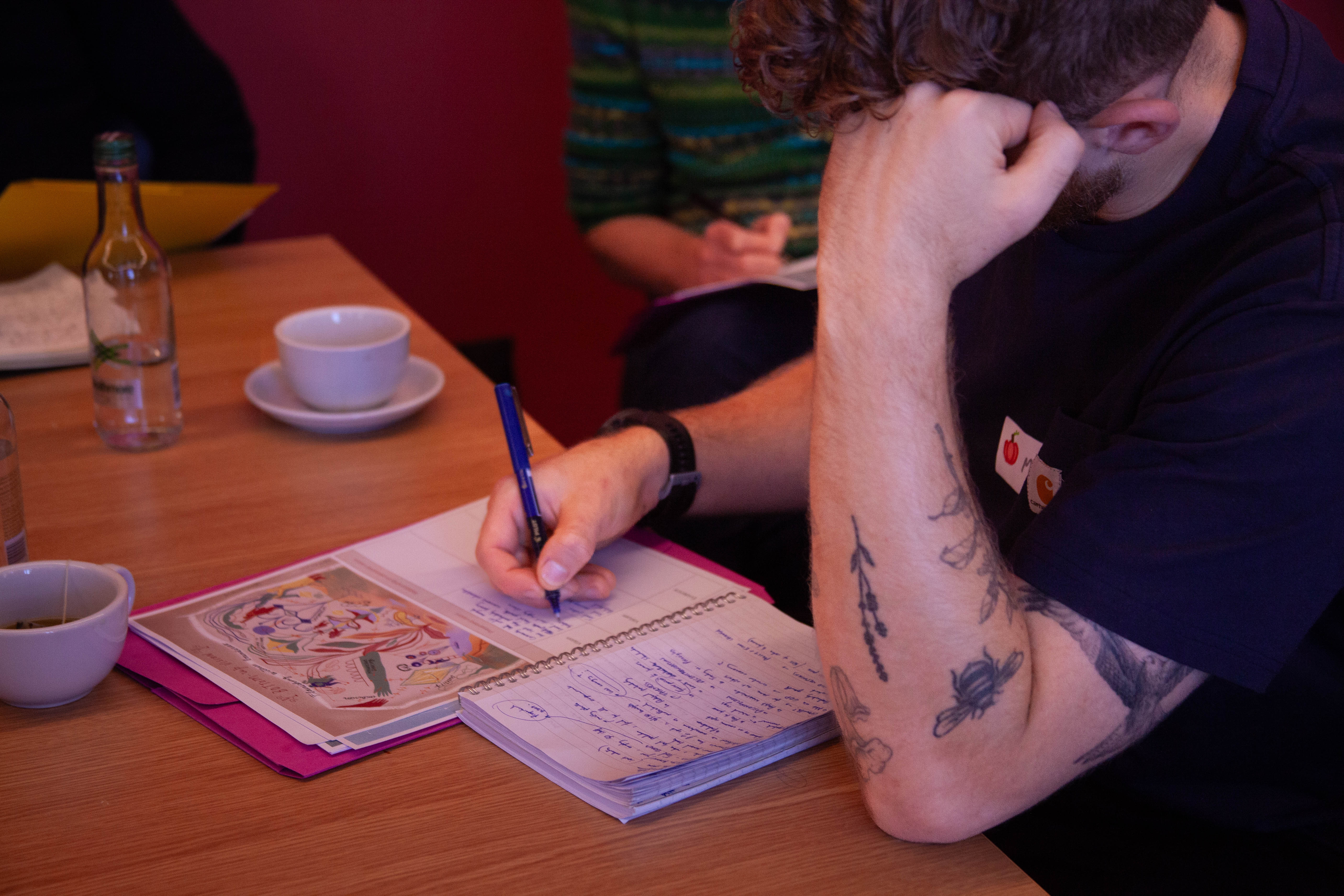

A workshop participant organises sticky notes. Photo by Jacquelyn Turner.

Methods: how did we do it?

On 2nd and 3rd October 2024, TABLE, in partnership with Healthy Food Healthy Planet and additional support from the Wellcome Trust, held a workshop which brought together a diverse range of stakeholders working across the food system to explore how they envisaged a better food future and the system transformations needed to get there. The participants included non-governmental and civil society organisations, policymakers, philanthropists, community leaders, and academics drawn from diverse disciplines. Together, over the course of the workshop, they discussed, developed, and refined different visions for the future of the food system. Through creatively engaging activities and panellist vision sessions, TABLE encouraged participants to delve beyond surface visioning activities to also scrutinise the values underlying them, the mechanisms and theories of change which underpinned them, and the political and economic approaches needed to progress them.

This workshop brought together academics (23%) with people working in finance (10%), non-governmental organisations (27%), philanthropy (4%), the food system supply chain (8%), and policy (13%). TABLE team members also joined in discussions, making up the remaining 15%.

We used methods rooted in futures thinking and visioning to foster discussions about the future of food, and prompted participants to collaboratively create new positive visions that explicitly consider the values underlying them and the economic and political approaches needed for change.

Both approaches are core to TABLE’s work. Futures thinking uses a suite of interdisciplinary methods to explore and critically consider scenarios that are possible, plausible, probable, or preferable to address specific problems (including those in the food system). These approaches work on the understanding that the future is not only unpredictable and uncertain, but likely to be as diverse, complex, and contradictory as the past and the present. Inclusivity and participatory methods are key components of these approaches, as well as using narrative development (or storytelling) as a tool for developing visions and bringing them to life.

WORKSHOP STRUCTURE

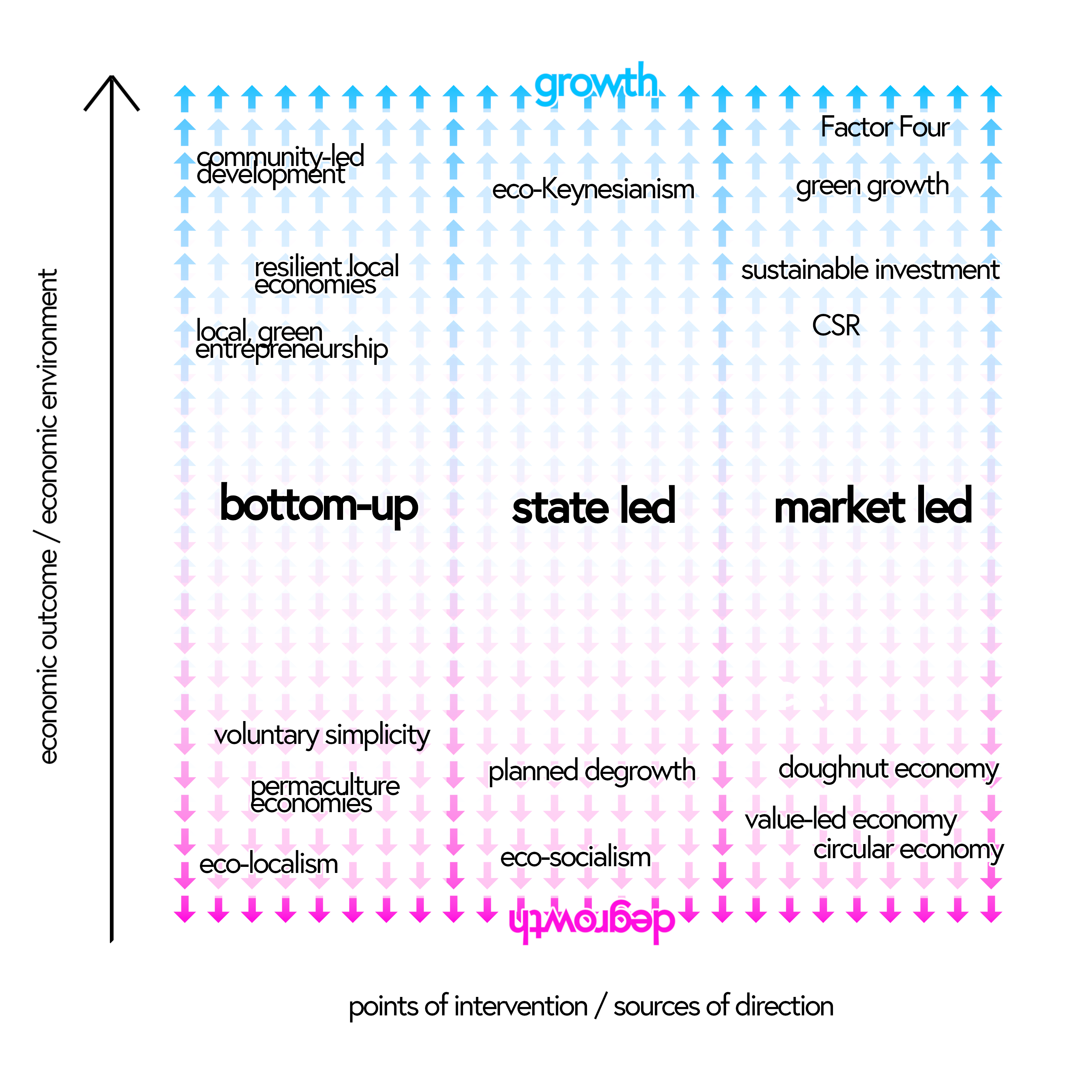

TABLE structured the workshop around three idea ‘seeds’ for possible visions of the future of food, derived from team members’ long-standing engagement with food systems discourse and knowledge of literature in the field. We describe these visions in more detail in Section 2 of this report, but, in brief, they are:

Market-led vision: This is founded in a belief in the transformative potential of the market to leverage a future food system that is healthy for both people and the planet and is socially conscious;

State-led vision: This a future in which the state leverages its power to restructure the food system with the goal of feeding people rather than producing profit, defining food as a democratic right rather than a commodity; and

Bottom-up vision: A vision which emphasises the transformative positive potential of building trust-based human relationships and connections at multiple scales, of the value of practical experiential knowledge, and of the need for decentralised production and provisioning systems. When combined, these elements can foster a future food system that works in harmony to create food that is healthy for both people and planet, accessible to everyone, and founded on fair livelihoods.

Having defined the initial seeds of these three visions internally, TABLE identified potential speakers working in relevant fields who we believed would be able to speak to and advocate for them. Three or four panellists were invited to one of three pre-workshop discussions, organised by vision cluster, to co-define each vision, discuss the workshop’s goals, and explore some of the questions we wanted them to address through their workshop presentations. Through these conversations, we added nuance, depth, and specificity to these visions. We then gave each speaker a brief for the workshop itself: to advocate for and describe their specific version of these visions based on their own values and experience in their fields. Professional artist Roberta Aita attended these discussions with the aim of visualising the futures impressionistically, to tap into people’s emotions and sense of possibility rather than producing literal representations. Roberta’s initial sketches went through three rounds of feedback and refinement with TABLE team members, and final versions were printed and displayed at the workshop as input and inspiration for workshop discussions (see Figures 4, 5, & 6).

We purposely asked speakers to develop the three presented seed visions rather than come up with their own ideas for visions, even though this led to more extreme versions of the visions which did not necessarily reflect and capture the nuances, contradictions and complexities of any one person’s views. Our rationale for this is that these more extreme versions represent the different poles of vision ‘axes’ we see in debates about the future of food. As such, we believe they are a useful structural tool for several reasons: first, the lack of nuance and complexity in the visions makes them easier to communicate and understand; second, the values for each vision are apparent, clearly defined and thus easy for participants to identify and discuss; third, more extreme and distinct visions are more provoking for participants, which helps reveal to them their own internal reactions and thus better understand their own personal values and how they relate to the vision; and, finally, the greater differences between the visions provide clear structure for the discussion and makes it easier to identify the visions’ strengths, weaknesses, synergies, and tensions. Our hypothesis was that this approach enables participants to ‘learn by doing’ and discover for themselves that future solutions are more complex and nuanced than they might expect.

WORKSHOP ACTIVITIES

The workshop was held in-person at the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford over the course of two days, and included a networking dinner on the first night to help participants develop their relationships and build more trust. We held six sessions in total, including: a welcome and introductory session on Day 1; three vision sessions spread out over the two days which included both panellist presentations and group discussions; and closing and reflection sessions at the end of each day. All participants were also asked to complete a virtual quiz about their own values, beliefs, and preferred vision both before and after the workshop as a way for us to see if changes in perspectives occurred as part of the workshop impact. Interested readers can take a version of the quiz here.

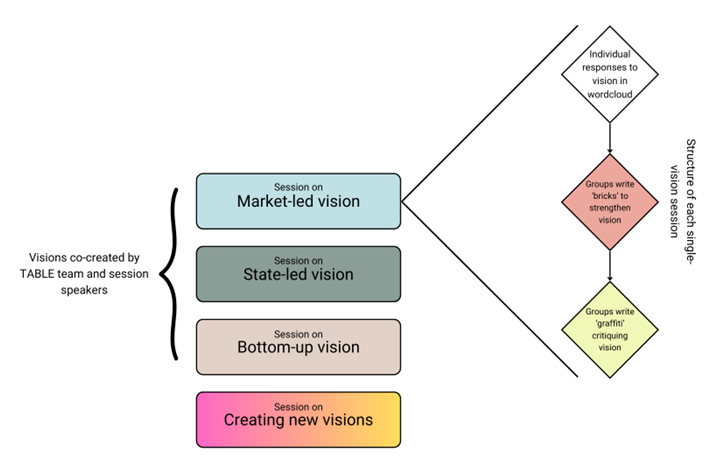

Each of the three vision sessions followed the same format (see Figure 3). First, panellists gave individual presentations advocating their version of the overall vision, while detailing their diagnosis of underlying food system problems, their proposed solutions, their interpretation of what growth means to them, and their personal values that underpin all of these. There was a short break, during which participants wrote down their reflections on the presentations, and then they reconvened into table groups. To encourage diversity and novel thinking, participants were asked to sit in groups with people who had different fruit or vegetable stickers on their nametags; each fruit or vegetable represented a specific type of stakeholder which remained unnamed to participants.

Figure 1. Virtual poll example answer

Discussion sessions began with silent reflection time for participants to consider their own values and thoughts about the vision in response to the panellist presentations. TABLE provided everyone with structured prompts to help guide this reflection time, as many participants were unfamiliar with or unused to thinking in this very deliberate way about values in their professional lives. To regroup and frame the discussion, participants wrapped up their reflections by taking part in an interactive anonymous poll where they provided up to three one-word responses to each of two questions: “What values lie at the heart of this vision?” and “What would we see around us if this vision were to come to pass?” (see Figure 1). The live results of the poll were projected on a screen and briefly summarised by a TABLE team member before participants moved on to group work.

A workshop participant writes down reflections on a provided worksheet. Photo by Jacquelyn Turner.

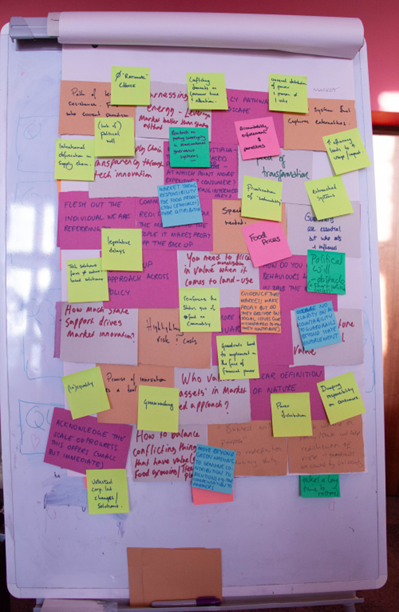

Discussion sessions began with strengthening the vision. For this, participants were asked not to critique, but to develop the vision that had been presented by building the best case for it and considering how it could be improved without compromising its core values. The point of this exercise was to try and counter the natural tendency to criticise positions that are different from one’s own before giving a fair hearing to the arguments, and without recognising what may be the very positive motivations that ‘opponents’ might have. In other words, we were trying to encourage people to think sympathetically and empathetically about other ways of thinking and other points of view. Groups recorded key ‘strengthening’ points on notecard ‘bricks’ which were then collected and used to build three separate vision ‘walls’ that were displayed throughout the workshop (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Vision wall example

Next, we asked each group to ‘stress-test’ the vision by identifying its obstacles, unintended consequences, neglected values, and conflicts with evidence. While this activity came more easily to participants, we still challenged them to frame their critiques in a constructive way with the aim of identifying gaps, blind spots, and inconsistencies rather than tearing down or weakening the vision overall. Participants recorded key points from this section on sticky-note ‘graffiti’ cards which were then added to the relevant vision wall as forms of feedback (see Figure 2). Finally, each vision session ended with whole-group reports which began with one table group then opened up to the rest of the room to contribute new points.

NEW VISION GENERATION

In the final session of the workshop on Day 2, participants worked in groups to develop new visions for future food systems based on the learning from the three vision sessions. We asked the panellists to work together as one group, while all other participants could select their own groups. We asked each table to develop a narrative for their own unique vision for a better food future, providing structured prompts to help focus discussions and designating specific amounts of time (10-15 minutes) for each one before moving on to the next. The prompts encouraged thinking about: key values; key actor groups; key roles for different actor groups (especially market, state and local communities); how each vision interacted with the physical world; and how to realise the vision (pathways to achievement). Participants had 80 minutes to develop their visions before sharing them with the whole group in story format.

Figure 3. Vision creation process