In this piece, Duncan Williamson reviews the Global Nutrition Report in the context of other developing food and sustainability policy.

Duncan has been working internationally in the field of sustainable systems for 20 years. For the last seven, has been leading WWF UK’s food work while also leading the international WWF Network’s position on sustainable diets and coordinating its work on sustainable food security- which recently co-produced a report with the Food Ethics Council entitled: From Individual to Collective action; exploring the business cases for addressing sustainable food security.

Duncan is the originator of WWF’s ongoing Livewell project, which demonstrates that a healthy diet can be sustainable. He also interacts closely with other organisations, including Eating Better , a cross sectorial coalition on NGOs working on meat consumption, where he is a director. An FCRN member since 2009, Duncan sits on the FCRN’s advisory board.

We have just seen a flurry of activity in the international arena with relevance to food. The SDGs have finally been signed off and at my count at least 8 of the goals and 65 indicators are connected to food. Prior to this and a little lost in all the noise, the Global Nutrition Report (GNR) 2015 was launched in New York. And later on this year, we’ll see thousands of policy makers and activists descending on Paris to – hopefully – agree a new global deal on climate change.

All these initiatives and activities quite clearly, overlap – and one of the major points of overlap is food, even if at times the different bodies feel disconnected. One of the key actions that comes out of this is the need for better collaboration between actors and sectors as Corinna Hawkes emphasises in her blog on the SDGs.

The Global Nutrition Report

The recently launched GNR is published by the International Food Policy Research Institute, and produced by a large independent expert group multiple organizations and an even larger stakeholder group. In short, it's a very thorough report and a great source.

Naturally the report’s focus is on malnutrition. It shows how malnutrition takes many forms: children and adults who are hungry, children so stunted they look three when they are really six, people who can’t fight infection because their diets lack nutrients, and people who are more likely to suffer from strokes because they are obese. Its key findings are summarised as follows:

Key findings:

1. Ending malnutrition in all its forms will drive sustainable development forward.

2. Although a great deal of progress is being made in reducing malnutrition, it is still too slow and uneven, some forms of malnutrition, namely adult overweight and obesity, are actually increasing.

3. Concrete action to address malnutrition, backed by financing, is being scaled up—but not nearly enough to meet the 2025 World Health Assembly (WHA) targets or the SDG target of ending malnutrition in all its forms by 2030. Commitment to and financing for nutrition will need to be ramped up significantly if we are to meet these eminently reachable global targets.

4. A virtuous circle of improved nutrition and sustainable development can be unleashed if action to address malnutrition in all its forms can be embedded within key development sectors.

5. The accountability of all nutrition stakeholders needs to improve if this virtuous circle between sustainable development and nutrition is to be fully realized.

6. Significant reductions in malnutrition—in all its forms—are possible by 2030.

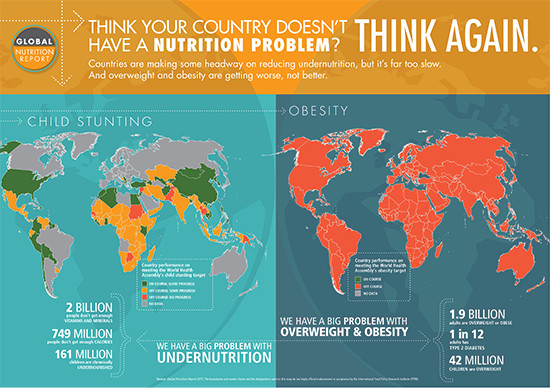

Malnutrition is global. One in three people on the planet experience it. According to the GNR, malnutrition represents a substantial drag on sustainable development. It inhibits wellbeing and the economy as well as our ambitions to be a healthy, fairer and more sustainable society. Some forms of malnutrition, such as stunting, are showing modest but uneven declines, others are stagnant. Still more, such as obesity, are on the rise.

Malnutrition is global. One in three people on the planet experience it. According to the GNR, malnutrition represents a substantial drag on sustainable development. It inhibits wellbeing and the economy as well as our ambitions to be a healthy, fairer and more sustainable society. Some forms of malnutrition, such as stunting, are showing modest but uneven declines, others are stagnant. Still more, such as obesity, are on the rise.

Two sets of global targets exist for malnutrition. The first is around maternal and child nutrition. Seventy four countries have five targets to combat this - of which 70 countries are meeting at least one of the targets. Only one country, Kenya is meeting all five.

The second set is adult overweight and obesity. It has three targets – and not a single country out of 190 is on course to meet all three. Only five will meet one target; 185 countries will not meet any.

Increasingly overweight, obesity and type 2 diabetes are the global nutrition and health problem.

Sustainable Development Goals

And then there are the sustainable development goals. The SDG framework should be a key component of an enabling framework for nutrition. But the GNR’s take on the SDGS is, in a word, critical. The SDGSs don’t address nutrition. Despite evidence that improved nutrition is a driver of sustainable development, nutrition remains underrepresented in the SDGs. Under SDG 3, health, but not food is not mentioned Out of 169 SDG targets, nutrition is barely mentioned.

And then there are the sustainable development goals. The SDG framework should be a key component of an enabling framework for nutrition. But the GNR’s take on the SDGS is, in a word, critical. The SDGSs don’t address nutrition. Despite evidence that improved nutrition is a driver of sustainable development, nutrition remains underrepresented in the SDGs. Under SDG 3, health, but not food is not mentioned Out of 169 SDG targets, nutrition is barely mentioned.

It becomes clear whilst reading the GNR that the problems associated with the food system are everywhere and as we move forward a new dynamic is needed. Nutrition needs to be built into different, new sectors and policy actions. It is time to think more systemically and for all of us to get out of our silos.

Notably, the GNR also digs into some really tricky issues, not least meat-rich diets and climate change. This is key – and welcome - for WWF and others in our sector.

Climate change

Disease, food, and climate are intimately linked. Any agreement at Paris in 2015 should present opportunities for those involved in nutrition and climate change to work together to advance their overlapping agendas. There is a clear link between the rapid move to meat-rich diets and health and growing environmental impacts. This problem is caused not just by the growth in beef, dairy and other forms for ruminant production, but also grain-fed animals such as pigs and poultry and the way feed is produced. Intensive livestock production potentially will lead to antibiotic resistance and more zoonotic disease.

To tackle this GNR authors are calling for less livestock production, coupled with actions to reduce consumer demand. For this to be successful they believe this is a need for the regulatory, fiscal, contextual, and sociocultural determinants of demand to be addressed. To start with national dietary guidelines should include environmental issues.

To tackle this GNR authors are calling for less livestock production, coupled with actions to reduce consumer demand. For this to be successful they believe this is a need for the regulatory, fiscal, contextual, and sociocultural determinants of demand to be addressed. To start with national dietary guidelines should include environmental issues.

Call for Action

There is no one size fits all approach. This is not an excuse for inaction. Nutrition and climate groups must come together to move forward these common goals. There are roles for civil society, government and business. A focus for action is COP21 in November 2015.

In connection to climate change the GNR identifies roles for different actors:

- Governments should build climate change more explicitly into existing and new national nutrition strategies including nutritional guidelines.

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change should develop a nutrition subgroup to ensure that climate policymakers take advantage of climate-nutrition interactions and community adaptation.

- Civil society should lead the formation of climate- nutrition alliances to identify new opportunities for action on both fronts.

Progress is being made: we are tackling hunger, albeit too slowly. At the same time we are sleep walking into another nutrition crisis that we need to address before it is too late. All forms of malnutrition are equally important. It is time to get out of our bubbles, and recognise the interrelated nature of the food systems. In the developed world we need to move away from meat rich eating patterns. In the other places we need to enable a transition to healthy sustainable diets without repeating the mistakes made the UK, the USA and other places. Overshadowing all of this is climate change. Without urgent action food will be less nutritious, harvests undermined and the poor will be most affected. It is hard to disagree with the conclusion of the report. We have a window of opportunity. Let’s take it. It’s time to work better together.

Post a new comment »