Tanzania’s traditional livestock grazing systems are under pressure. As population growth and economic growth increase demand for milk and meat, farming is also facing the effects of both climate change and the allocation of grazing land to other uses including conservation and urban development.

Dr David Dawson Maleko, lecturer, researcher and consultant at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania, considers the potential solutions for enhancing milk and meat production in the face of these challenges. He discusses the challenges and trade-offs both of intensifying production and of government-led allocation of new grazing areas to herders.

About the author: David Dawson Maleko is a lecturer, researcher and consultant at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania, East Africa. He has a Ph.D. degree in the field of Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystems Management from the Nelson Mandela African Institution of Science and Technology, Tanzania. He holds an M.Sc. in Conservation and Land Management from Bangor University, UK. David has been responsible for a wide range of scientific research, advice and outreach specialising in sustainable natural resources management particularly rangelands ecology and management, and integrated animal-plant climate-smart agriculture in East Africa.

1. Overview of drylands and their use in Tanzania

Tanzania is a country located in Eastern Africa with a total land cover of about 947,300 km². Tanzania has been experiencing both human population and economic growth that creates more demand for animal source food including milk and meat. The human population in Tanzania has increased five-fold since the first census in the country, from 12.3 million in 1967 to 61.7 million in 20221 . About a third of this population lives in urban areas with a significant proportion of middle-income groups, which can afford meat and milk-based foods. The GDP of Tanzania was consistently increasing at a rate of 7% for a decade before the effect of global pandemic COVID-19, which reduced it to about 2% in 2020, followed by an increase to 4.3% in 2021. The country is categorised as a low-income country with most of the population especially those in rural areas living on less than 1.9 USD per day.

It is estimated that about 4.9 million rural households are engaged in livestock production and own 90% of the total 33.9 million cattle, 24.6 million goats, and 8.5 million sheep in the country as of the year 2020. Most of these households keep indigenous livestock breeds of cattle, goats and sheep, which are raised under extensive traditional systems where animals wander over a large area in search of pasture and water.

Tanzania is endowed with a diversity of ecosystems including humid highlands receiving a minimum of 800 mm of rainfall per annum, categorised as arable land suitable for intensive crop production. Most lowland areas (67% of the country’s land) are categorised as dry sub-humid to semi-arid areas (drylands), most being marginal for high water demanding crops. Wetlands, valley areas suitable for irrigated agriculture, and surface water resources are excluded from the aforementioned proportion of drylands in the country.

In Tanzania, drylands are mainly used for wildlife conservation including national parks such as Serengeti and extensive livestock grazing by traditional herders such as Maasai. About 44% of the total land area in Tanzania is protected for wildlife and forest resources conservation. Wildlife protected areas (National parks, Game reserves, Game Controlled Areas and Wildlife Management Areas) cover at least 28% of the total land area of the Mainland Tanzania. Forest reserves (natural forests and plantations) cover about 16%. Human activities including settlements, crop farming and livestock grazing are prohibited in protected areas of Tanzania. Also, both consumptive and non-consumptive resource utilisation including hunting, fishing and logging are highly regulated within protected areas and permits are always required.

The purpose of this article is to describe the traditional/extensive livestock production system in the drylands and its challenges, consider the potential measures available for enhancing milk and meat production and their possible trade-offs, and then considering where consensus might lie as to how sustainable food production can be achieved in a changing climate.

2. Traditional livestock production systems under pressure

In Tanzania, cattle farming for meat and milk among other benefits is a widespread occupation among the rural community. Furthermore, traditional herders depend on these livestock breeds for food (e.g. meat and milk), income, insurance, and draught power, and the breeds form a crucial part of their cultural tradition. The traditional livestock production system in the country has been affected by several factors in recent years.

Pastoral kids drinking milk and a pastoral woman herding calves in semi-arid Tanzania during a dry season – Milk is an important protein source for the pastoral community especially children (Photo credit – DD Maleko)

Climate change has led to an increase in drought frequency and intensity in the drylands thereby limiting water and eventual pasture availability. For example, in the droughts of 2021-2022 over 92,000 livestock (mainly cattle, sheep and goats) died due to a lack of water and pasture in one semi-arid pastoral district in Northern Tanzania2 . Frequent droughts are affecting livestock production and hence food security and livelihoods. In Tanzania, the poverty rate in 2018 was estimated at 30% among agricultural households (livestock keepers included) which was four points above the national average (26%). In the country, poor people are considered to be those living on less than 1.90 USD per person per day and unable to meet their basic consumption needs including proper meals, clothing and shelter3 .

Cattle drinking water directly from a dam in semi-arid Tanzania – bad practice leading to damage and siltation of surface water resources (Photo credit – DD Maleko)

Climate change puts further strain on traditional systems due to changes in rainfall patterns that reduce grass regeneration and forage availability while increasing the distribution range of some noxious weeds and alien invasive plants. The most notorious invasive species in the drylands of Tanzania include Prosopis juliflora (mesquite), Parthenium hysterophorus (carrot weed), Astripomoea lachnosperma (choisy), Hygrophila auriculata (marsh barbell), Trichodesma zeylanicum (cattle bush) and Gutenbergia cordifolia. Livestock do not graze these exotic plant species due to their toxicity or inherent physical protection in form of sharp and thick thorns. Henceforth, if left uncontrolled these species end up quickly replacing the palatable indigenous grasses and legumes.

Cattle pulling a cart carrying thatching grasses (among traditional uses of livestock), and dry H. auriculata (marsh barbell) weed in the fields in Central Tanzania during dry seasons. H. auriculata replaces palatable grasses, herbaceous legume and forbs in grazing areas of Tanzania which are seasonally or occasionally flooded (Photo credit: DD Maleko).

Grazing land reallocation is another major challenge and limits herder mobility whilst previously grazed lands are reallocated for other uses such as conservation, crop farming, mining, infrastructure and urban development. Land reallocation puts more pressure on the remaining land and causes overgrazing which is said to be among the causes of land degradation. In Tanzania, the land is state-owned and administratively land falls under three categories namely village land, general land and protected land. However, these land categories are poorly demarcated and sometimes pastoralists unknowingly encroach on protected lands in search of pasture. Under these conditions, reallocation can be done forcefully4 . In village lands, which account for most of the country’s land, land tenure rights are allocated by doing development such as farming and building houses. However, most pastoral societies do not develop the land due to their migratory nature, hence they lose land rights to other users, mostly settled farmers. Hence, they find themselves gradually being displaced to marginal dry lands often with limited grass and water resources but with dense shrub and bush covers with sparse bare lands.

Therefore, livestock keepers are taking various measures to sustain their livelihoods and adapt, including changing their herd composition by keeping more goats and fewer cattle. Goats are natural browsers for which bushes and shrubs comprise most of the diet, as opposed to cattle, which are grazers relying much on grasses. Other adaptive measures include digging boreholes and shifting to crop cultivation (maize and beans) and some are moving out of agriculture altogether to other economic activities. This trend undermines meat and milk production and threatens national food security. Crop cultivation in these drylands is highly unpredictable due to frequent crop failures that add more burden to the government to provide food aid to dryland communities.

Top row: Goats browsing on shrubs and being supplemented by nutritious pods of Acacia tortilis during dry season in the semi-arid rangelands of Northern Tanzania. Goats are being adopted by pastoralists as a strategy for climate change adaptation due to their ability to tolerate drought and feeding on woody vegetation resources (leaves, twigs and fruits) as opposed to cattle. Bottom row: Goats foraging in bushes and shrubs during dry season where grass is scanty and of poor quality. Here they eat tender leaves, leaf litter and fruits (Photo credit: Marco K. Laizer).

The aforementioned challenges prompted the government to adopt various policies aiming to improve livestock production, alleviate poverty among traditional herders and protect the environment. Some of these policies and strategies are the Agricultural Sector Development Programme (2017), National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (2005), National Livestock Policy (2006), National Climate Change Strategy (2012) and Tanzania Livestock Masterplan (TLM, 2017-2022). The TLM is the most recent and detailed plan to improve livestock production in the country, focusing on the improvement of feed availability, markets, livestock breeding practices and veterinary services among traditional herders in the Tanzanian drylands.

3. Is intensification a solution?

Cattle are the most preferred livestock species in Tanzania to the point that they are synonymous with livestock. Milk and red meat consumed in the country mostly come from cattle and goats, while sheep are utilised for meat but not milk. The Short-Horned Zebu (SHZ) cattle is the most dominant indigenous cattle breed in East Africa with an average live body weight of about 250 kg when matured. The SHZ cattle can go up to three days without drinking water in hot and dry environments. In addition, SHZ cattle have been reported to be resistant to some tick-borne diseases prevalent in East Africa such as East Coast Fever, Anaplasmosis and Heartwater as well as Trypanosomiasis disease, which is spread by tsetse flies. These diseases can be very devastating to exotic cattle breeds in such a way that farming them in drylands without proper prophylactic measures, such as spraying of acaricides5 against ectoparasites and vaccination, is impossible.

Cattle and sheep herded in poor pasture with significant bare soil during a dry season in semi-arid Tanzania (Photo credit – DD Maleko)

Average cattle milk yields are very low in the traditional extensive systems, ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 litres/cow/day in the dry seasons and 1.5 to 2.0 litres/cow/day in the wet seasons. In improved systems (commercial), yields can reach 6.5 to 12.3 litres/cow/day during the dry and wet seasons, respectively6 . The cattle milk yields in Tanzania are very low compared to those of dairy cattle in the developed world, for example the United Kingdom where the average yield is about 21 litres /cow/day.

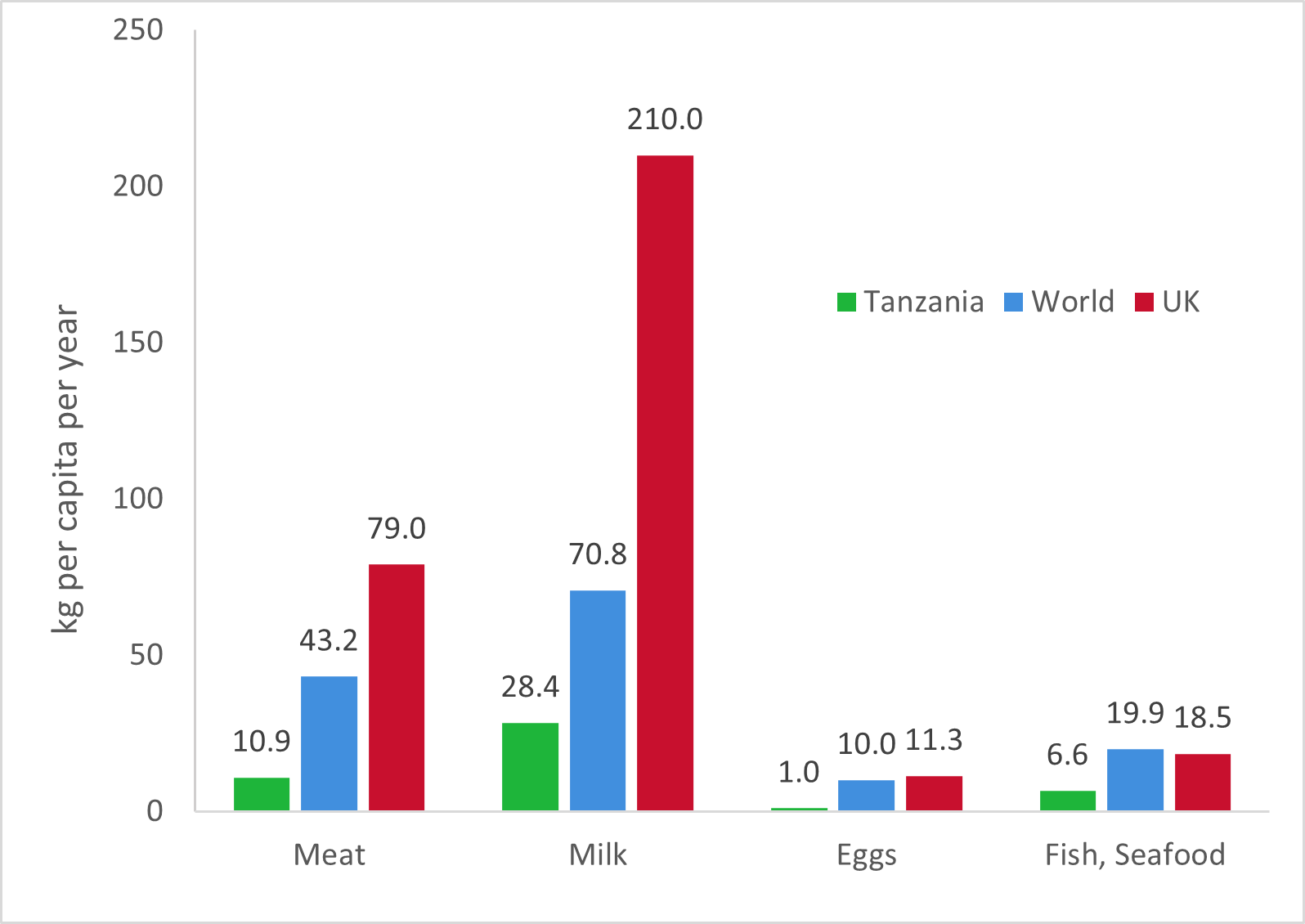

The average yearly consumption of meat in Tanzania is 11 kg per person – far less than both the global average of 43 kg and the higher levels found in many developed countries, for example 79 kg in the United Kingdom. As illustrated below, the picture is similar for other animal-sourced foods, with Tanzania’s consumption of milk, eggs and fish/seafood all being well below the global average7 . The reasons for such low per capita animal-source food product consumption in Tanzania are low productivity and limited access, especially in rural poor populations8 .

Image: Yearly consumption per person of meat, milk (excluding butter), eggs and fish/other seafood, for the year 2019. Data source: FAOSTAT Food Balances. Figure produced by TABLE.

These are among the factors contributing to the prevalence of malnutrition in Tanzania, where 32% of the children aged under five years were reported to experience stunting9 . The situation is worse among traditional livestock keepers: here, one survey showed that 35% of children under five were underweight10 . The reason for the higher malnutrition rate among herders is their reliance on milk and meat as the main source of protein since their culture prohibits them to eat fish, eggs, pork, or wild meat due to associated taboos e.g. fish is considered the same as a snake in Maasai culture. Also, traditional livestock management practices contribute to food insecurity, since there is a tendency for men to migrate with the whole herd over long distances in search of pasture and water, leaving behind young, old and sick animals for the rest of the household to rely on in dry seasons. The weak and unproductive animals that are left at home cannot provide milk and meat for the household. The rationale behind leaving these weak animals at home is their unfitness for trekking to distant pastures and water resources. To cope with food insecurity, poor pastoralists, in particular women and the elderly, keep goats and poultry (to sell for urban consumption, providing income) and engage in small-scale farming of seasonal crops such as legumes, maize and tobacco. They may also take part in additional trades such as selling beads, garments and traditional herbal medicines.

Moreover, it is well documented that highly productive beef and dairy cattle breeds that achieve slaughter weights and start lactating at younger ages do reduce lifetime GHGs emissions per animal and per unit product. Conversely, poor livestock performance increases greenhouse gas emissions per unit of animal product due to poor food conversion efficiency leading to delayed growth. This necessitates keeping large numbers of animals in large units of land for meat and milk production, culminating in deforestation and desertification. It is reported that between 2010 and 2017 in Tanzania, crop cultivation and fires were the major driver of deforestation followed by livestock keeping11 . There have been suggestions to plant drought-resilient indigenous grasses such as Cenchrus ciliaris (African foxtail grass), as well as to replace low-yielding livestock breeds with high-yielding exotic breeds to make extensive livestock production more efficient.

Although these intensification measures could increase livestock production and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they are not without trade-offs. The introduction of new grass species could lead to the disappearance of native vegetation, which is also relied upon by wild herbivores, local communities for medicines, and pollinators including bees and butterflies. Also, replacing indigenous livestock breeds with exotic ones can cause a loss of indigenous animal genetic resources which might be essential for future livestock breeding programmes and for adapting to the effects of climate change, such as high temperatures and the spread of disease. Moreover, exotic breeds and their crosses will be more demanding in drylands due to harsh conditions and high disease and parasite prevalence. Other foreseen problems due to livestock intensification in drylands include management of previously field-dropped manure, since collecting and spreading it could be expensive due to limited farm machinery availability. Manure heaping could increase nitrous oxide and methane emissions while improved manure management for biogas (syngas), bio-slurry and bio-char production is poorly adopted in the country. Culturally, herders might be reluctant to adopt the exotic breeds since the indigenous breeds have other traditional values apart from meat and milk, such as dowry payment, rituals and pride. For example, the indigenous Tanzania long fat-tailed sheep (TLS) and red maasai sheep (RMS) are much preferred over exotic sheep breeds because the massive fat tail is believed to have high medicinal and nutritional values and is hence used to feed sick people and nursing mothers.

It is clear that livestock intensification could lead to a further ecological and cultural crisis in the drylands of Tanzania. Several measures could be employed to enhance livestock performance and food security while maintaining the traditional livestock production system.

The first option is improving breeding through the selection of indigenous livestock breeds. Unfortunately, breeding programmes in the country have only focused on exotic breeds and their crosses and not on identifying and promoting the best performing indigenous breeds under natural field conditions.

The second measure is promoting appropriate rangeland use practices including sensitising the pastoral societies to keep animals within carrying capacity, embrace planned rotational grazing and improve quality pasture availability and control soil erosion through planting drought-resistant native forage grasses such as Cenchrus ciliaris (African foxtail grass), Eragrostis superba (Maasai love grass) and Enteropogon macrostachyus (mopane grass). In addition, this measure could include conservation of native fodder shrubs and legumes (agro-silvopastoral) in grazing lands through controlling wildfires and their excessive harvesting for fuelwood and charcoal making.

Grass strips in a maize field for soil erosion control and for dry season livestock feed supply in semi-arid Tanzania – good practice (Photo credit -DD Maleko)

The third measure would be to develop a niche market for indigenous breeds’ products e.g. meat and milk, as opposed to the current situation where herders sell live animals or raw milk to middlemen traders at local markets who usually offer very low prices to herders but sell at high prices in urban areas. A niche market can increase the market value of animal products and create an incentive for herders to invest in their livestock. Additionally, the integration of herders into formal value chains could help to get milk from the farm to the market and reduce post-harvest losses of milk, especially during rainy seasons when the milk is in abundance. Integration is also expected to increase food safety and create more employment opportunities. There are further changes required in drylands management for livestock production systems to be sustainable in Tanzania, as discussed below.

4. Is land re-allocation a solution to herders-conservation-farmer conflicts?

Historically, pastoralists have relied on access to large expanses of land managed as common property for grazing in East Africa. However, the rapid human population increase and concerns about wildlife conservation have led to the reallocation of historical livestock grazing lands to conservation and other land uses. Shrinkage of grazing lands has reduced herders’ mobility, leading to overgrazing of the remained small parcels of communal grazing areas. Overgrazing and overstocking are the main reasons for drylands degradation, characterised by loss of palatable grass species, weed and bush encroachment, loss of biodiversity and soil erosion.

Cattle and donkeys grazing in poor dry maize stover (crop residues) with significant bare soil in semi-arid Northern Tanzania – A bad practice that tends to damage soil and escalate conflicts with crop farmers (Photo credit – DD. Maleko)

Herders have been keeping more goats as a result, due to their small body sizes and their ability as browsers to eat bushes as the source of feed, in contrast with cattle and sheep, which are grazers. Additionally, there has been an increase in conflict among different land users such as farmers, conservationists and herders over access to water and pasture. The conflicts between farmers and herders can sometimes turn deadly whereby herders and farmers kill each other, in addition to property destructions, as in the cases of Kilosa and Kiteto districts in Eastern and Northern Tanzania respectively12 . Moreover, herders together with their livestock have a tendency to illegally trespass or encroach on protected areas during dry seasons. This practice puts them into conflict with conservationists and threatens public health and food security because interactions among wildlife, livestock and humans increase the chances for transmission of diseases, including malignant catarrhal fever and East Coast Fever (ECF) to cattle, and Anthrax and Rabies to both human and livestock. Wildlife species are reservoirs of most of these diseases.

Traditional herders, namely Maasai, do not hunt or eat wild animals and they have existed in harmony with nature for millennia, but the pattern seems to shift nowadays. Shrinkage of livestock grazing areas due to both human and population growth has led to overstocking to the extent that wildlife is replaced by livestock in dryland grazing areas historically known to be occupied by both livestock and wildlife. Additionally, herders are responsible for the retaliatory killing of predators, e.g. lions, African wild dogs and hyenas, which are hunting livestock as the result of the displacement of their regular prey, which includes African buffalo, gazelles, impala and wildebeest.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) is an example of how wildlife protection and land utilisation for livestock grazing can be pitted against one another. The site is a protected multiple land use area where wildlife and livestock are owned by Maasai herders, wildlife and land are state-owned and the site is designated as a World Heritage Site. There have been questions about the sustainability of the existing NCA management model as the result of environmental degradation due to increasing numbers of livestock and humans. It is debatable whether Maasai are truly the reason behind NCA degradation, as opposed to the limitations placed upon them or the need to expand tourism in the site, which is the second most visited tourist destination in the country. Nonetheless, the government has allocated new grazing land and is advocating for the voluntary relocation of herders from NCA to Handeni district in North Eastern Tanzania, which is a good conservation initiative. The government is allocating the herders with free grazing land of about 10 acres and a house built of concrete block walls and corrugated iron sheets upon relocation for each household. In addition, water, health and school infrastructures are being developed for ensuring herders' social wellbeing at the relocated site.

Cattle grazing in a pastoral family pasture reserve during dry season in semi-arid Tanzania – good practice (Photo credit – DD Maleko)

Grazing land allocation and voluntary relocating of herders is a commendable step and sets a new direction in the country so as to ensure food security and improve livelihoods among herders. However, it could be argued that the areas of land allocated to each household are unlikely to be managed sustainably in the long term, since it is the tradition of the Maasai pastoralists to keep large herds of livestock, which could lead to overgrazing. Therefore, strict laws to keep livestock populations within carrying capacities need to be in place. Also, it is possible that the move of the herders into the new area could escalate the conflict with other land users, e.g. farmers and other livestock keepers who were already living there and the mobile nature of pastoralists. Land users’ conflicts could be addressed by a clearly defined and considerate land use plan which will account for each group’s needs. There are chances that conflict will still exist over water resources despite the presence of land use plans due to prolonged droughts exacerbated by climate change. Therefore, allocating grazing land alone is not enough. There is a need for a network of grazing lands and migration corridors to facilitate herder mobility during environmental hazards, similar to those existing for wild animals in the country. The Land Use Planning Act (2007) and Grazing-Land and Animal Feed Resources Act (2010) offer legal frameworks for planning and allocating new grazing lands at the village or district levels. These allocated lands could be managed by a state-supported pastoral-led parastatal13 institution, which could provide legal protection for grazed areas from reallocation and secure herders’ grazing rights.

The inception of the said parastatal will be a meaningful approach and full measure aiming to not only protect drylands but also to make traditional/extensive livestock production systems sustainable in the context of climate change. The parastatal could be entrusted with assessment of the condition of the drylands and could engage in grazing land improvement practices such as prescribed burning, bush and weed control, controlled grazing and reseeding. Otherwise, Tanzania could risk increased conflicts among different land users, food insecurity due to population and economic growth, and poverty, especially among traditional herders.

5. Conclusion

Food security and animal-sourced food product consumption is still low in Tanzania, linked to malnutrition, especially among children under five years old. Moreover, the vast majority of the country’s extensive production of livestock for milk and meat still takes place in poor conditions, with slow growth, poor feed conversion efficiency and low yields. Milk and meat production in the drylands of Tanzania are facing several challenges including climate change, less productive indigenous cattle breeds, and the increasing shrinkage of livestock grazing lands. Climate change in the drylands of Tanzania is characterised by low and erratic rainfalls, and frequent drought recurrences leading to limited water and eventual pasture unavailability. Rapid human and livestock population growth under limited land use plans are escalating land degradation due to overgrazing and improper crop cultivation that accelerates vegetation cover loss, soil erosion, and desertification in the drylands of Tanzania. Unplanned migratory practices of herders have kept them in constant conflicts with other land users such as conservationists and crop growers in the country.

Therefore, the production of meat and milk among traditional herders in Tanzania faces several challenges as narrated above and its sustainability is debatable. This piece has suggested different measures to increase livestock production among traditional herders in Tanzania to enhance food security and protect the environment. These measures include selective breeding of indigenous livestock breeds, livestock marketing improvements and a countrywide network of well-coordinated grazing lands management plans to ensure pasture, water and market access. I argue that these measures would make the traditional/extensive livestock system more sustainable and mitigate food insecurity and conflicts among different land users in the country.

Footnotes

- 1Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (2022), https://www.nbs.go.tz/index.php/en/

- 2The citizen News - Drought kills 92,000 livestock in Simanjiro, https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/drought-kills-92-00…

- 3Belghith, N. B. H., Karamba, R. W., Talbert, E. A., & De Boisseson, P. M. A. (2019). Tanzania-Mainland Poverty Assessment 2019: Executive Summary. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1266932/tanzania-mainland-poverty-a…

- 4Brockington, D. (1999). Conservation, displacement and livelihoods. The consequences of the eviction for pastoralists moved from the Mkomazi Game Reserve, Tanzania. Nomadic Peoples, 3(2) 74-96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43124089

- 5Pesticides that kill ticks and mites.

- 6FAO (2019). Options for low emission development in the Tanzania dairy sector - reducing enteric methane for food security and livelihoods. Rome. 34 pp. https://www.fao.org/3/CA3215EN/ca3215en.pdf

- 7Source: FAOSTAT Food Balances 2019. The figures for milk consumption exclude butter.

- 8Michael, S., Mbwambo, N., Mruttu, H., Dotto, M.M., Ndomba, C., Da Silva, M., Makusaro, F., Nandonde, S., Crispin, J., Shapiro, B., Desta, S., Nigussie, K., Negassa, A., Gebru, G., 2018. Tanzania livestock master plan https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/100522

- 9UNICEF (2018) Tanzania National Nutrition Survey 2018 https://www.unicef.org/tanzania/media/2141/file/Tanzania%20National%20N…

- 10Lawson DW, Mulder MB, Ghiselli ME, et al (2014) Ethnicity and child health in northern tanzania: Maasai pastoralists are disadvantaged compared to neighbouring ethnic groups. PLoS One 9:e110447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110447

- 11Doggart, N., Morgan-Brown, T., Lyimo, E., Mbilinyi, B., Meshack, C. K., Sallu, S. M., & Spracklen, D. V. (2020). Agriculture is the main driver of deforestation in Tanzania. Environmental Research Letters, 15(3), 034028.

- 12Benjaminsen, T. A., Maganga, F. P., & Abdallah, J. M. (2009). The Kilosa killings: Political ecology of a farmer–herder conflict in Tanzania. Development and change, 40(3), 423-445.

- 13A parastatal is “a fully or partially state-owned corporation or government agency” (source).

Post a new comment »