Over the past decades, Colombia’s dominant agricultural vision has been that of becoming a food powerhouse: a nation that could “feed the world”. However, while Colombia’s exports of some tropical produce have increased, this expansion overseas has not led to improvements in the living conditions of the millions of people in rural areas who still experience poverty and food insecurity and malnutrition.

Agrarian movements have long sought to put forward alternative visions of the food system under the narratives of i) feeding the nation and ii) feeding the village. These alternative visions are based on a more localised approach to agriculture and food consumption that values aspects such as people’s proximity to food production, protection of local environmental resources, urban-rural links and the importance of promoting rural and urban well-being through healthy diets.

This essay explores the tensions between these alternative visions of food provisioning. It is written by Dr Felipe Roa-Clavijo, Assistant Professor at the School of Government of Universidad de Los Andes.

About the author: Dr Felipe Roa-Clavijo is an Assistant Professor at the School of Government of Universidad de Los Andes. In his research, he analyses the debates around food provisioning from the perspective of agrarian movements, the state, consumers and the food industry.

Introduction

Agriculture plays an important role in Colombia for both its food exports and domestic consumption. The country combines different types of agriculture and food production that include small-scale agriculture, family farming, agro-industry, and the food industry, as well as a diversity of producers from peasants to medium farmers and corporations. There are also a variety of actors involved in the process. Smallholders for example produce coffee, fruit, and vegetables for both domestic consumption and exports. Large agriculture produces sugar cane, palm oil, banana, and plantain mainly for export, and the food industry produces processed and packaged foods with both domestic and imported inputs.

Man in White Button Up Shirt Holding Green Bananas, Sucre, Colombia. Image credits: FRANK MERIÑO, Pexels, Pexels Licence.

Over the past decades and following the trajectories of neighbouring countries such as Brazil and Argentina, Colombia’s dominant agricultural vision has been that of becoming a food powerhouse: a nation that could “feed the world”. To this end, the country has embarked on expanding its participation in agricultural global markets via free trade agreements. This is a process that started back in the 1990s with the adoption of globalisation policies and new regulations on international trade. Following the recommendations of multilateral organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the national government cut most of the finance and support it previously offered to smallholders and also withdrew all state projects of agrarian reform and land re-distribution. As a result of these decisions, the social and economic situation of millions of smallholders and rural dwellers has stagnated. Following these international guidelines and in a new stage of market liberalisation, Colombia signed in the last decade free trade agreements with the European Union, the United States, and economic blocs such as South America’s Pacific Alliance, among others.

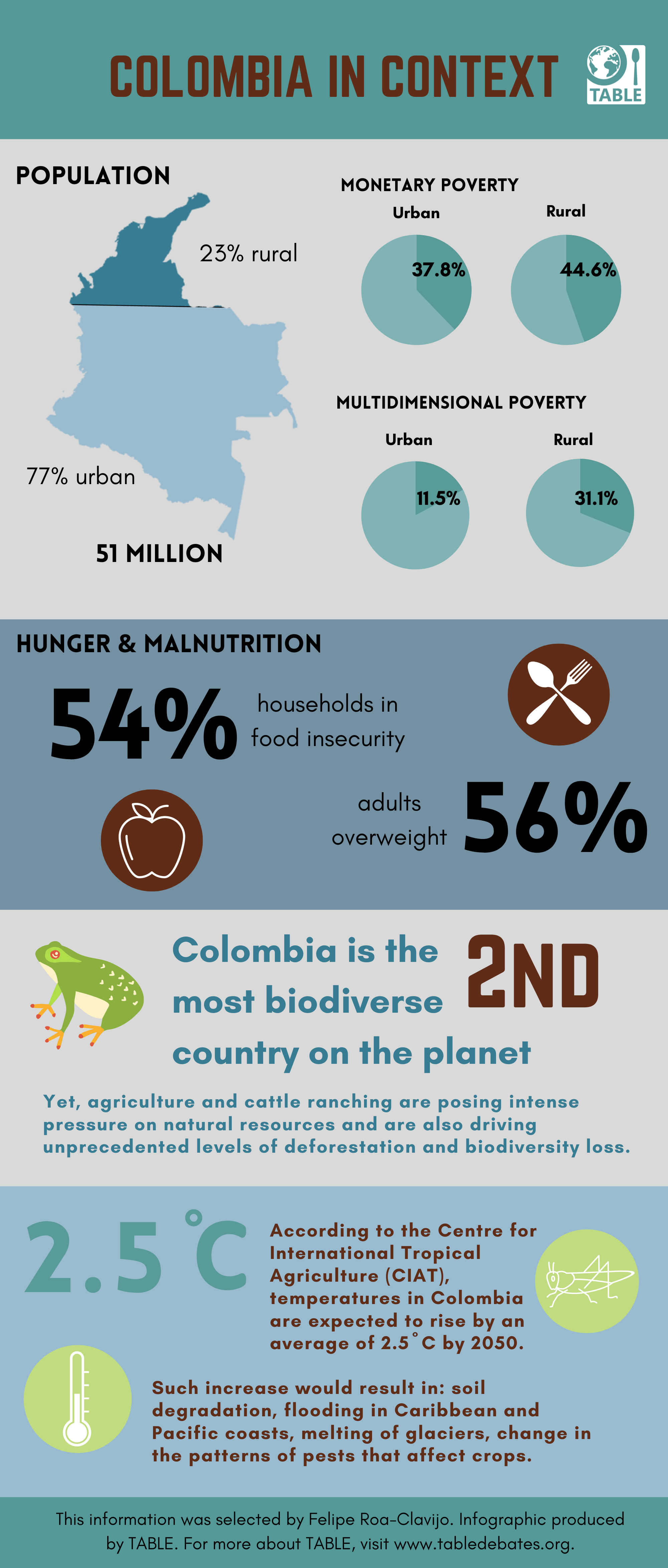

As a result, while Colombia’s exports of some tropical produce have increased, this expansion overseas has not led to improvements in the living conditions of the millions of people in rural areas who still experience poverty and food insecurity and malnutrition. More than 50 percent of the national households (54%) live in food insecurity conditions, and nearly 60 percent of adults (56%) are overweight according to the latest National Food Security and Nutrition Survey (ENSIN, 2017).

People living in rural areas, those who work in and depend on agriculture as their main livelihood, experience worse conditions than their urban counterparts. Both monetary and multidimensional poverty are higher in rural areas, being 44 and 31 percent respectively compared to 37 and 10 percent in the urban areas.

Furthermore, the country is in a continuous struggle to build a more peaceful, inclusive, and prosperous society. Having signed, in 2016, a peace deal with Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), the oldest guerrilla movement of the western hemisphere, the national government is now working on implementing the agreement. Its first chapter, the Comprehensive Rural Reform, seeks to address the structural problems of the countryside by providing access to land, implementing special programmes to support smallholder agriculture, and investing in public goods and social programmes for rural areas such as education, health, and infrastructure.

The government’s new approach also encompasses fresh thinking on food. Whilst the dominant vision has been that of “feeding the world” with an export-oriented approach to food and agriculture, agrarian movements have long sought to put forward alternative visions of the food system under the narratives of i) feeding the nation and ii) feeding the village. These alternative visions are based on a more localised approach to agriculture and food consumption that values aspects such as people’s proximity to food production, protection of local environmental resources, urban-rural links and the importance of promoting rural and urban well-being through healthy diets.

Why is it relevant to look at these tensions and particularly at alternative visions of food provisioning? Because recent socio-political and economic transformations in the country have created a space for alternative voices to be heard. Furthermore, in the context of global shocks such as the pandemic of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, which have disrupted food systems in various ways, many countries around the world are rethinking their dependency on the global market and are looking for ways to foster stronger and more resilient national food systems. The ongoing debates in Colombia about feeding the village, the nation or the world can provide important insights for these global concerns.

Emerging tensions and competing visions in food systems

In the following paragraphs I outline both the ‘old’ globalist vision for food production, which I call ‘feeding the world’ and the alternative visions that are now gaining more traction, ‘feeding the nation’ and ‘feeding the village’. For each of these, I explore the main actors that promote these visions and the context in which they emerged, their main pillars, and their implications for food and agriculture.

Feeding the world

Over the past decades, the dominant food system vision in Colombia has been that of seeing the country as an agricultural and food powerhouse: a highly agricultural, agro-industrial and food industry country with strong ties to international trade. The main promoters of this vision have been the national government, the agroindustry, and the food industry.

These stakeholders’ vision of the food system has two main pillars. First is the expansion and maximisation of the opportunities provided by globalisation. Actors in this alliance seek to increase international trade, both imports and exports. To this end, and in full support of this vision, previous national governments have embarked on expanding global markets by signing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with other countries. Over the past 10 years Colombia has signed FTAs with, among others, Canada (2012), the United States (2012), the European Union (2013) and Israel (2017).

The second pillar is a productivist approach – the goal of maximising agricultural and industrial production through a diverse set of technologies. For agroindustry actors, this implies relying on Green Revolution technologies including high-yield crop varieties, fertilisers, and pesticides. With this approach, Colombia has become in the past decades a lead producer and exporter of tropical produce, including palm oil, coffee, sugar, beef, and avocado. For the food industry this implies accessing low-cost primary agricultural products – both domestically-produced and imported – to increase the production of processed foods. The food industry in Colombia is a lead producer of pasta, cookies and canned foods at the national level, and a lead exporter of candies.

This perspective of the food system aligns with and has received significant support from international and multilateral organisations such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Back in 2015, the IDB published a report called The Next Global Breadbasket: How Latin America Can Feed the World: A Call to Action for Addressing Challenges & Developing Solutions that lays out a vision of a dynamic and export oriented agro-industry and which has been influential to policymaking in the region.

The vision of a dynamic international and domestic food market based on industrialised methods and technologies has been key in shaping Colombia’s economic strategies over the past three decades.

Feeding the village and feeding the nation

This dominant, concentrated and consolidated view of the food system has, until recently, lead to the side-lining of other perspectives, mainly coming from poor and marginalised farmers who have different priorities, values and interests to the larger, more powerful stakeholders mentioned previously. These alternative visions see the food system’s role as being, respectively, to feed the village and to feed the nation. Promoted mainly by small and medium farmers, these visions emphasise the importance of local production and consumption, short distribution circuits, agroecology, environmental protection, and the national market. As we will see below, both visions are overlapping but have, at the same time, key differences.

Two main groups promote these alternative visions, both of which emerged nearly 10 years ago. The first is Cumbre Agraria Campesina, Étnica y Popular (Agrarian, Peasant, Ethnic and Worker´s Summit – CACEP), which is an alliance of local organisations and cooperatives, including peasant groups, indigenous and African-Colombian communities, that promotes a vision around feeding the village. Their vision is that of a localised food system – feeding the village – in which families, communities and cities are inter-connected by local food production and in which food systems use a diversity of indigenous and African-Colombian traditions and knowledge. They also emphasise the importance of protecting the environment. To this end, they promote the use of agroecological farming practices, as well as the protection of forests, soil, and water.

The second group is Dignidad Agropecuaria por Colombia (Agrarian Dignity for Colombia – DAC), which promotes a vision around feeding the nation. Its members are mainly medium-size farmers and agricultural entrepreneurs. As an umbrella movement, its main sub-groups are organised by agricultural value-chain, mainly those of dairy, potato, onion, coffee, and legumes. Their main vision is to “feed the country” by supplying these staple foods to the national market. For this reason, they adopt a nationalist agenda, and oppose food imports of all agricultural products that could be produced in Colombia. In this endeavour they have had intense discussions with the national government due to the current imports of dairy products, mainly from the European Union, and potato, mainly coming from Peru.

CACEP and DAC are aligned in certain areas but disagree in others. For example, under the discourse of food sovereignty, both groups seek to defend national agriculture and take a protectionist approach against food imports. However, whilst for DAC this protectionist approach is about having control over the domestic market, for CACEP it is about human rights and social justice. In line with and connected to social movements such as La Via Campesina, CACEP seeks social justice by advocating for land distribution, the reduction of inequality and poverty eradication for rural dwellers.

In other words, while both social movements advocate for alternative visions of the food system, the values and identity that inform their political agendas are different. DAC members consider themselves to be rural entrepreneurs. They approach agriculture from a business-oriented perspective which values aspects such as efficiency and productivity. In this same line, they promote conventional methods of agricultural production, mainly through the use of Green Revolution technologies. Because of this, another discussion that they have had with the government is about the price of agricultural inputs. Colombia is a net importer of fertilisers and pesticides and hence is subject to international price fluctuations. DAC is demanding that the government protect them against this price instability, particularly when the price sharply rises. In this endeavour, it has been successful in getting the government to respond, at least in extreme cases, to the fertiliser price spikes, by taking measures to alleviate such costs.

In contrast, CACEP members see themselves as diverse rural communities that belong to different indigenous, African-Colombian and peasant groups. For them, agriculture is not just a business activity. Rather, it is embedded in their core identities – and provides meaning to their culture and to the territories that they inhabit. Connected with this is the fact that CACEP promotes agroecological principles in farming and the protection of the environment, particularly of soils, water and forests. To this end, they advocate for the government to design policies and support agroecological production at a national scale, an element of their agenda that up until now has not been successful.

In spite of the lack of representation in both the executive and legislative branches of the state, the main space for contestation of CACEP and DAC has been social mobilisation in the streets. In my book, The Politics of Food Provisioning in Colombia, I analyse the agrarian protests that took place in 2013 and 2014 and the agrarian negotiations that lasted until 2018 between these agrarian movements and the state. Since then, and in spite of the little progress that has been made in the negotiations of their agendas, there have been more social protests, both rural and urban, urging the national government to address the worrying inequality experienced by millions of people across the country, particularly in rural areas.

But times are changing

People Walking at the Plaza de Bolívar, Bogotá, Colombia. Image credits: Jose Vasquez, Pexels, Pexels Licence

In August 2022, President Gustavo Petro was elected as the first left-wing president in the history of Colombia. He takes office alongside the country’s first ever African-Colombian Vice-President Francia Marquez. In line with the visions of both CACEP and DAC, they won the Presidential office on the basis of many promises, among them to eradicate hunger everywhere, to exploit the country’s full agricultural potential with a social justice perspective and to strengthen the nation’s path towards food sovereignty – a term that has been controversial and neglected in the past. Petro’s new government will give space in the political debate to discuss food sovereignty.

The new government, in line with the visions of DAC and CACEP, is now putting forward some strategic approaches that include three main elements. First, renegotiating free trade agreements, so that the country, particularly its agricultural sector, is not at disadvantage compared to other countries. While the particular actions have not been specified at this point in time, this probably refers to providing more financial support and technical assistance to smallholders, elements that were withdrawn decades back as part of the deals’ agreements.

Second, prioritising domestic agricultural production with an emphasis on reducing grain dependency. The first announcements of the government point to the design of a programme to increase domestic wheat and corn production, since Colombia is currently highly dependent on imports from Canada and the United States.

Person Holding A Yellow Corn, Bolívar, Colombia. Image credits: FRANK MERIÑO, Pexels, Pexels Licence

Third, doubling the efforts to eradicate hunger through a special presidential programme that will provide humanitarian assistance to populations in need, and special support to vulnerable communities to build resilience and long-term food security.

At the core of the political transformation is the fact that some agrarian leaders who are part of the national agrarian movements mentioned above and who have been mobilising for over a decade, have now been elected as Congressmen. The leaders from both DAC and CACEP ran for Congress in the March 2022 election. These leaders, Robert Daza and Cesar Pachón, were elected with Pacto Historico – the political party of the new President – and inaugurated on 20th July. Both of them have promised to work towards the interests and visions of their agrarian movements as Congressmen. Together, they are already working on a legislative package that includes the recognition of peasants (along the lines of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas), agrarian reform and agroecological production.

Where next?

It’s been only a few months since the start of the new Congress and the new government. The main changes are yet to be seen in the coming months and years. However, the fact that a new government and Congress that has alternative visions of the food system has been elected represents significant political change. The next four years will be full of intense debates about food and food systems transformations.

In this context, it will be interesting to see and analyse how dominant visions of feeding the world interplay with the new government and Congress visions of feeding the nation or the village. Will the government continue to be a strategic ally of agroindustry and food industry companies? What will be the relationship between the government and agrarian movements? Furthermore, in the context of climate change and environmental degradation, will environmental protection and practices such as agroecology, water and soil conservation feature at all in the political debates and in the practical implementation of socio-economic programmes?

One would expect that given the new political landscape, marginal visions of the food system, particularly those alternative perspectives addressed in this piece, will now take more of a centre stage. The key aspect is whether those who hold leadership positions now can translate those visions into concrete outcomes that improve living standards, produce healthy food, and help the planet.

Finally, recently elected presidents in Latin America include Gabriel Boric in Chile and Luiz Inacio Lula in Brazil, both of whom are politically aligned with Gustavo Petro. It is therefore likely that they will seek to forge alliances to strengthen both the region’s position as a global food exporter and their efforts to reduce hunger and malnutrition, which have been deteriorating in the last years.

Post a new comment »