Introduction

The last 15 years have seen increasing debate and attention by different actors regarding food’s role in our multiple ongoing crises (climate change, rising inequality, hunger, and malnutrition), the need for food systems´ transformation, and food’s important role in the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It is agreed that food systems need transformation at multiple dimensions, scales, and places, to achieve sustainability, equity and resilience. One such debate is whether or not our food system needs to work with nature or be more natural.

This year, TABLE is working on the theme of Nature, considering how ideas about nature and what is natural inform debates about what and how we should eat, grow and conserve the products of nature (plants and animals). What we understand by the words 'nature' and 'natural' vary enormously - much of that understanding is informed by culture, landscape and experience and so has a geographic and regional component. Moreover, given the complex dependencies and interconnections of the challenges of both local and global food systems, and the diversity of societies around the globe, a specific issue can be addressed in different, contradictory, or complementary ways. What seems the same challenge or event might, in two different parts of the world, have different patterns and underlying structures and values.

TABLE has an opportunity to explore these differences and similarities as it expands the scope of its work into Latin America through an alliance with The School of Government of the Universidad de Los Andes in Colombia and the Institute of Social Research from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. This blog entry is part of this expansion, and it aims to reflect the aforementioned geographic diversity across our work, discussing how the topics covered in TABLE´s Nature theme are present or not in the debate in Colombia, what the differences are, and what other topics or angles exist in the country.

Livestock, climate, and food debates

In a global context, livestock systems are one of the main producers of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. According to FAO, in 2015 livestock agrifood systems contributed to 6.2 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions, representing 12% of all anthropogenic GHG emissions and about 40% of total emissions from agrifood systems. Additionally, livestock production has other environmental impacts regarding water use, eutrophication, land use and biodiversity loss; both directly and through the feed-food competition. Besides, the impact that meat consumption has on human health depends on the type and quantity of meat, as well as on genetic and socioeconomic factors. Yet, there is a relatively established consensus that a healthy diet should include lower amounts of animal protein (as compared with the standard Western diet) and that a high consumption of red meat and especially processed meat is associated with increased risk of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes[1].

The impacts of livestock systems and meat production on food systems’ health and sustainability are an area of growing interest and concern the world over. The health effects of a diet high in meat consumption and the environmental (un)sustainability of certain livestock systems, as well as the global growth in the sector as a whole, are much debated, as are the alternative diets and farming systems needed to address those impacts (TABLE’S explainer on “Meat, metrics and mindsets” explores these issues in some detail). These debates play out in Colombia, as in other parts of the world. Nonetheless, in many parts of South America, and particularly in Colombia, these debates have additional layers that shift the conversation in different directions, and build upon motivations that emerge very specifically from national context.

As shown in the series of resources produced by TABLE under the title “Meat: the four futures”, a large part of the debate in western societies focuses on the type of diet one should follow and the production and consumption policies that enable or restrict those alternatives. In Colombia the debate builds on the country´s socio-political history and its geographic condition as a tropical and megadiverse country. In the next sections, I will try to address some of these elements. First, I will comment on the relation between livestock, the country's armed conflict and Amazon deforestation; then I will give some brief ideas regarding a more natural production and consumption, touching on Colombia's latest regulations on UPF and public procurement, as well as some progress in agroecology.

Cows, deforestation, and peace in Colombia

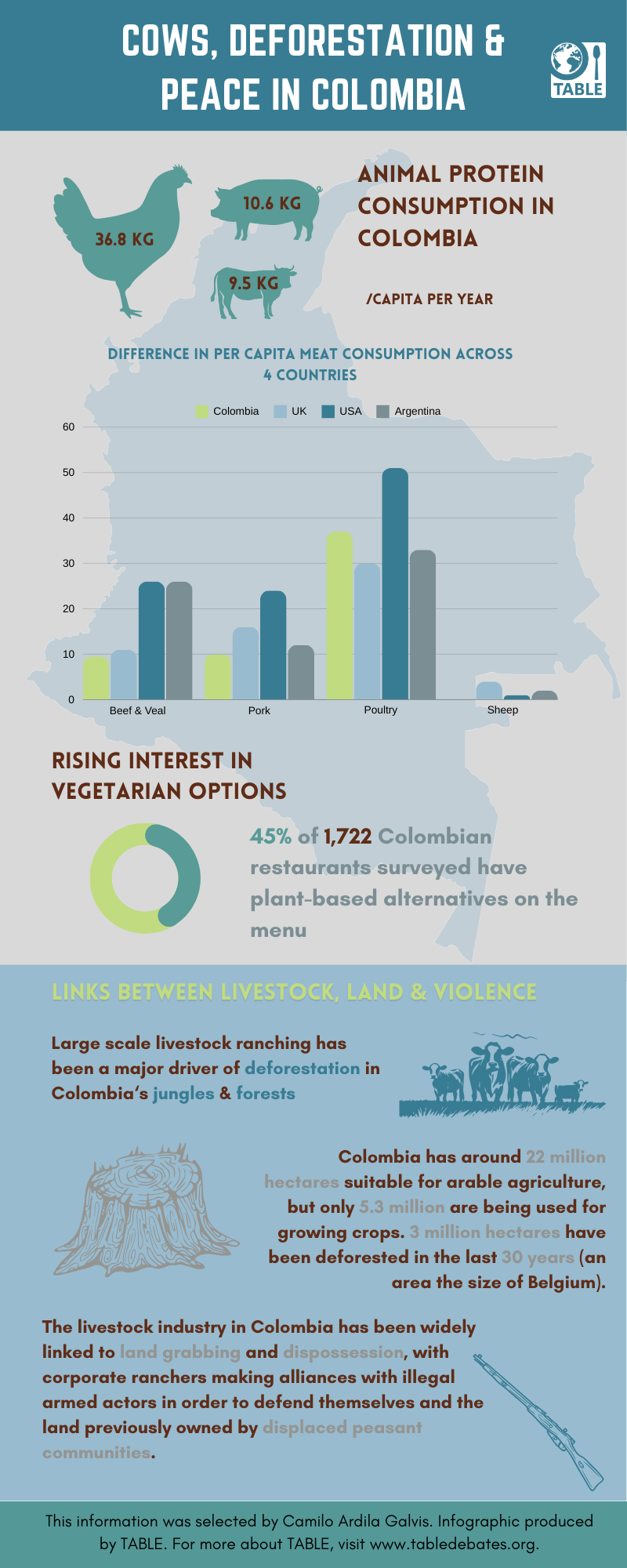

Colombia has a diversified meat basket, with poultry as the main source of animal protein (36.8 kg/capita per year) followed by pork (10.6 kg/capita per year) and beef (9.5 kg/capita per year). Except for chicken, the country´s meat consumption levels are lower than those in Argentina, UK, or the OECD average (see the table below). That said, in recent years, the consumption of fish, chicken, and especially pork has increased, gaining space from beef, partially due to the rising cost of the latter. Likewise, plant-based alternatives have been expanding during the last decade. Despite the lack of robust and official data, some independent studies, like a recent one from the Colombian Association of the Gastronomic Industry confirms the increase in consumer interest in plant-based meals and the availability of vegetarian and vegan options in restaurants. The study found that between January 2022 and June 2023, interest in vegetarian dishes increased more than 150%, while preference for vegan food has experienced a growth of 433%, and from 1,722 restaurants analyzed, 45% have plant-based menu alternatives. However, the fact that these restaurants are located in the main cities (Cartagena, Bogotá, Medellín, among others), catering to upper-middle income groups and European tourists; and that plant-based burgers and pizzas made up to 60% of consumer searches in these restaurants, suggests that this is more a market opportunity and a ‘fashion’ tendency than a behavioral change founded on environmental and health considerations. Further research and dialogue should delve deeper into this, as there has not been major debate on meat consumption or plant-based diets in Colombia. One of the reasons for this is that meat production and livestock systems in the country generate deeply political and sensitive debates around context-specific issues such as land-use conflict, armed conflict, and deforestation.

Kilograms/capita | Colombia | UK | USA | Argentina | OECD average |

|---|

Beef and veal | 9.5 | 11 | 26 | 36 | 14.4 |

|---|

Pork | 10.6 | 15.7 | 23.8 | 11.6 | 22.9 |

|---|

Poultry | 36.8 | 30.6 | 50.9 | 38.5 | 33 |

|---|

Sheep | 0.1 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

|---|

SUM | 57 | 61.1 | 101.1 | 86.1 | 71.6 |

|---|

Source: OECD -FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021

For a start, large scale livestock in Colombia has been widely linked to land grabbing and dispossession during the country´s 60-year ongoing armed conflict[2]. Large-scale livestock farmers and corporate ranchers have made alliances with illegal armed actors, most of them paramilitary groups, in order to defend themselves against other armed actors, but also to access land previously owned by displaced peasant communities and to legalize this dispossession by using or creating networks between ranchers, paramilitary groups, local governments, and other actors. This is a very complex issue, with different modalities of dispossession and many actors involved besides large-scale livestock farmers. To give a sense of the scale of these issues, the Colombian Truth Commission highlights that, based on data from the National Victims Survey, from 1985 to 2013 more than 537,000 families were dispossessed of their land or had to forcibly abandon it. Similarly, between 1995 and 2004, more than eight million hectares were dispossessed or abandoned, a territory similar to the size of Austria.

Secondly, large scale livestock ranching in the country has been one of the main drivers of deforestation in Colombia´s jungles and forests. A recent study found that during the last 30 years, illicit land-use change from forest to cattle was responsible for over 3 million hectares of deforested land[3] (about the size of Belgium). This has been particularly dramatic outside of the agricultural frontier (areas where agricultural activities are excluded by law) and following the Peace Agreement in 2016. A recent study by Dejusticia (a Colombia-based NGO that focuses on action-research for legal and social studies), following an investigation of the Environmental Investigation Agency (an international NGO with offices in London and Washington that investigates and campaigns against environmental crime and abuse), stresses that despite having tools to control the risks of deforestation associated with the supply of meat, livestock production is increasingly a major contributor to deforestation in the Amazonas region of Colombia. Among the tools available to the Government are information systems to track livestock and their origin in deforestation hotspots; a regulatory framework that restricts both livestock production in environmentally protected areas and the movement of cows through the country; and several voluntary non-deforestation agreements with companies. Nonetheless, international trade opportunities for Colombian beef seem to only aggravate the problem, as exports are expected to grow due to new international partners like China. Currently, the main markets for Colombian beef are Chile, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Russia (before the sanctions due to the conflict with Ukraine).

Lastly, there is a major land-use conflict between crop farming and livestock farming. Colombia has around 22 million hectares suitable for arable agriculture, but only 5.3 million are being used for growing crops. In contrast, there are about 15 million hectares suitable for livestock farming (pastures), while 35 million are currently being used for this purpose, with most of the additional land coming from arable land and forests. This land-use conflict is exacerbated and interconnected with the outstandingly unequal concentration of land; the top 1% of the largest farms hold 81% of the land, while the other 99% of farms have access to 19% of the land. Most Colombian livestock is managed under extensive systems; an Oxfam analysis based on the 2014 Agricultural Census pointed out that one million peasant farmers have less land than is used by an average cow in Colombia!

Given this complex and troubled context, public concerns and debates about livestock in Colombia tend to focus much less on the GHG emissions arising from the sector or on the role of meat in the diet, but rather on these deeply political issues of land use, land dispossession-restitution and deforestation.

A more natural production

There is an ongoing debate in Colombia related to bringing nature into the food system, from a production perspective and in relation to the adoption of more sustainable and natural approaches to agriculture. Upon the agreement that food systems, and especially agricultural production systems, need to transform to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis, different groups of actors have been promoting different approaches like organic agriculture, regenerative agriculture, or agroecology. The need for more sustainable approaches is evident. Colombia has one of the highest consumption of agrochemicals in Latin America with its use of fertilizers at 4.8 times the average of the OECD. Similarly, 40% of the soils are eroded and it is estimated that by 2040 there will be an average 7.4% reduction in productivity of a series of crops (especially corn, potatoes, and rice) due to climate change[4].

Given this context, several sustainable approaches have been promoted in the country in recent decades: sustainable intensification, climate smart agriculture, organic agriculture, regenerative agriculture and, more recently, agroecology. The country, with the leadership of the Ministry of Agriculture and the active participation of peasant organizations, is advancing in the construction of the national public policy for agroecology while the Congress is discussing a public bill on the same matter. However, there have been very few debates, if any, about how different sustainable agriculture approaches will benefit from these new policies, and what common ground agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and organic agriculture share, at least in relation to environmental sustainability and biodiversity conservation. As shown in TABLE’s diagram “Exploring the ebbs and flows of Regenerative Agriculture, Organic and Agroecology”, despite differences in the dimensions and the underlying concerns of these approaches, there is valuable common ground in the farm practices that they promote, their focus on the need to preserve natural resources, and the aim of achieving sustainable and resilient farming systems. Although I subscribe myself with agroecology (from my academic background and my consumer choices), I believe that there is an urgent need to transcend what separates these approaches and to generate common actions from what unites them: promotion of farm biodiversity, carbon sequestration and ensuring soil health.

More natural consumption: Dietary changes and bringing nature onto the plate

In a country where 56.4% of adults are overweight or obese and 24,4% of children between 5 and 12 years old are overweight[5], questions of diet take up a lot of health discussion. The question of Ultra-Processed Food (UPF) is another topic that has been receiving growing attention in Colombia, as elsewhere.

The global debates around UPF comprise a variety of issues, from their nutritional health impacts to (corporate) power imbalances and questions about how far the individual has (or should have) free choice when deciding what to eat. Some of these discussions, from a UK/European perspective, can be found in TABLE´s document about the UPF concept; in the paper exploring the connections between soy, land use change, and discussions on animal- versus plant-based protein sources; as well as in the TABLE’S forthcoming work (a Feed episode on ´The Power of UPF´, a Letterbox series on UPF, and an essay on UPF and naturalness).

One of the areas of debate around UPF concerns the need or desirability of regulating the production or commercialization of these products, or from another perspective the importance of giving consumers enough information to consume healthier food. Latin America and the Caribbean are leading in this regard: all 35 countries across the region have discussed front-of-package labelling, 11 countries have formally adopted it and 7 countries have started implementing it (Chile, Argentina, México, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay, and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela)[6]. This is, partially, a consequence of collective regional efforts that kicked off in 2014, when Member States of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) approved a five-year Plan of Action whose central goal was to halt a further increase in obesity, particularly in children and adolescents. This plan called for the implementation of fiscal policies (health taxes), the regulation of food marketing and labelling, improvements in school nutrition and physical activity environments, and promotion of breastfeeding and healthy eating. The plan also contributed to the Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model and Sustainable Health Agenda for the Americas 2018-2030.

Pictures of front-of-package labels from selected countries of Latin America

Colombia has recently adopted two regulations regarding UPF. First, the Law 2120 from 2021 establishes the obligation, for all manufacturers and importers, to have front-of-package labelling in all edible products if these contain excess sodium, sugar, saturated fat, trans fat, or if they contain sweeteners. Moreover, it defines these products according to their processing level (NOVA classification) and accounts for recommendations from the WHO and PAHO. The Law is regulated by the Ministerial Resolutions No. 810 from 2021 and No. 2492 from 2022. The latter has adjusted the labels to be octagonal and to comply with WHO´s recommendations. However, the situation for consumers is confusing and there is need of pedagogical campaigns. This is especially the case now that, due to the change of the label´s shape and the transition period allowing companies to adjust their labels, we can find on the shelves products with circular labelling, others with octagonal labelling and others without front-of-package labelling but that are classified as UPF. It is expected that from the 15th of June 2024, all products must comply with the regulation.

The second regulation approved by the Congress of Colombia in November 2022 is a tax reform that included (in Article 54) a health tax on “junk food” (sugary beverages and ultra-processed foods)[7]. The tax will come into force gradually between 2023 and 2025, and it is seen by supporters like the NGOs Dejusticia or RedPaPaz, and the Government of Colombia, as part of public health policies and as a milestone in reducing the prevalence of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs). However, some critics of the tax, like big sugary beverages industries and the National Association of Merchants FENALCO, have stated that the tax will mainly affect low-income consumers and ´corner stores´. Additionally, the exemption of some UPF products, besides the medical ones (see box), raises the question of whether there will be an increase in the consumption of these exempted products rather than a general decrease in the consumption of UPF as the tax intends.

Comments (0)