Dr Alexandra Sexton is a geographer and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and has been studying the socio-political aspects of cellular agriculture and plant-based alternatives since 2013. She is currently a researcher on the 'Livestock, Environment and Planning' (LEAP) project funded by Wellcome's Our Planet, Our Health initiative.

This blog is an overview of the open-access article Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins written by Alexandra Sexton, Tara Garnett & Jamie Lorimer and published in Environment and Planning E: Nature & Space. Its findings were also included in a recent World Economic Forum report entitled ‘Meat: The Future Series – Alternative Proteins’.

Image: Impossible Foods Media Kit, Oakland Plant 14

When we eat food we eat stories. Think about your last trip to the supermarket. Many of the labels will tell you of the places and people that have brought the different products to the aisles. A family farm in North Yorkshire, a cocoa grower in Ghana. They may also feature images of those places and people, and sometimes the animals involved in production. There may be accompanying stories of social justice, environmental care and healthfulness told through traffic light systems and the logos of certification schemes (e.g. Fairtrade, Soil Association). At the very least, most food comes packaged with stories of its taste. Millions of dollars are spent on these particular narratives by food businesses. The “finger lickin’ good” of KFC. The “Taste the Difference” of Sainsbury’s. The slow-motion sequences of melting chocolate, sizzling steaks and fizzing wines of Marks & Spencer’s. All are designed to get us tasting the products before we’ve even touched them. Taste, along with price and convenience, has been shown to be one of the biggest drivers of how and what we choose to eat.

My recent work has been examining the stories or narratives used to promote a range of food products that have been making global headlines over recent years. Frequently heralded as the ‘future of protein’, these approaches include a new generation of plant-based proteins, edible insect products, and a group often referred to as cellular agriculture. Within this latter group you’ll find lab-grown/cultured/clean/cell-based meat, milk and egg products, all of which are united by their approach of using cell science techniques to grow animal-derived foods in vitro, i.e. outside the animal body (see Stephens et al. (2018) for overview of the technical, socio-political and regulatory aspects of cellular agriculture). The intention behind growing cells instead of animals is to remove the need to raise animals intensively and the need for their slaughter.

A particular type of narrative – often referred to as ‘promissory narratives’ in social studies of science and technology – has driven the development of these recent products. This type of narrative is largely defined as the promises and future expectations upon which technological innovations depend to gain the momentum needed for their development, particularly in the early stages (Brown & Michael 2003). Often these techno-driven promises offer visions of a better future – e.g. pest-resilient crops or the eradication of human diseases. The promise of economic opportunity also tends to feature, although often directed at particular audiences (e.g. investors, retailers). A key feature of promissory narratives is the work they do in the present to turn their utopian visions into reality. In the case of the recent alternative proteins, their promissory narratives have worked extremely hard to create awareness across a variety of audiences (investors, retailers and the general public), and ultimately convince people to invest in them, stock them, or put these novel products in their shopping baskets. See also Stephens (2013), Jönsson (2016) and Mouat & Prince (2018) for discussion of alternative protein promissory narratives.

Yet for cellular agriculture, there are currently no products available on the market to purchase anywhere in the world. For the last decade, they have existed almost entirely as promises of what they will achieve once they get to market, rather than as tangible, eatable products. Even for the plant-based and insect products that have recently launched in a selection of Western countries, their narratives promise an all-round better alternative to conventional animal foods; or in the case of insects, that they actually qualify as ‘food’ at all.

We might think that the promises companies make about their products are simply part of the business of marketing. While this is certainly true, we can look beyond the marketing formulas to explore what other roles promissory narratives can serve. This exercise can also highlight the ‘situatedness’ of these narratives – in other words, how they sit within, reflect and reinforce broader ideological, institutional, economic and cultural systems at a given time. As mentioned above, the promises of an innovation almost always come packaged with a vision of delivering something better than the status quo. Here, then, we have a snapshot of how the status quo has been interpreted and found wanting in certain ways. This snapshot provides a valuable window into a set of beliefs – themselves embedded within ideological and institutional networks – that have resulted in a diagnosis of a ‘problem’ followed by an offering of a ‘solution’. Promissory narratives thus offer a way to examine these diagnoses and solutions as products of their contemporary (and historical) contexts. This enables us to ask critical questions concerning the who, what and why of their contexts: for example, who has created the narratives, and for what ends; who are the intended audiences; what cultural representations do they (re)inforce; what messages and data do they emphasise; and who/what is missing from them?

This was the critical approach that my colleagues and I used in a recent paper called ‘Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins’. We wanted to understand what kinds of promises have been made across all three categories of alternative products (plant-based, insects, cellular agriculture) - in other words, what types of ‘goodness’ have been attached to these products by their developers to convince different audiences that they are better than conventional animal foods. By examining the official websites, social media accounts and product labelling of the main companies, we identified five key promises that have been working across these three categories of alternative proteins (see Table 1).

|

TABLE 1 | Promissory narratives of alternative protein companies |

|||

|

|

Promise |

Description |

How was this communicated (selected examples)? |

|

1. |

Healthier bodies |

The promise of being healthier than conventional animal foods. This claim was made both in terms of what the products did contain (e.g. high protein) and what they didn’t contain (e.g. no antibiotics). |

1. Comparisons of nutritional content between alternative and conventional animal products. 2. Emphasis on high protein levels, and absence of growth hormones, antibiotics and cholesterol. 3. Graphics of muscly arms and endorsements by professional athletes to assure the high protein levels |

|

2. |

Feeding the world |

The promise of being able to feed the projected growth in global population using fewer planetary resources. |

4. Emphasis on two numbers: 9 billion people by year 2050. 5. Statements that the current food system is ‘broken’ and ‘out-of-date’ 6. Statements that we need to produce more food to feed this projected population growth. 7. Another number – 2 billion – representing the population currently experiencing under-nutrition and poverty, specifically in Global South. |

|

3. |

Better for the environment and animals |

The promise of offering more environmentally efficient production. Also, the promise of removing the need for rearing large livestock in intensive conditions and the need for their slaughter. |

8. Comparisons of the land use, water use and greenhouse gas emissions between alternative and conventional animal products. 9. Statements highlighting the potential benefit of slaughter-free meat for the 66 billion animals currently slaughtered annually as livestock worldwide. |

|

4. |

Control for sale |

The promise of increased food safety and traceability. This claim is based on relocating the production of meat, dairy and eggs away from the ‘risky’ biologies of living animals to the controlled, optimised environments of technoscience. |

10. Promises to replace the disease-prone conditions of (intensive) livestock production with the “safe and sterile” conditions of laboratories and factory-like facilities.1 |

|

5. |

Tastes like animal |

The promise that these alternatives will not only be good for us and the planet, but they will also be indistinguishable in taste, appearance and how we shop and eat them. This claim assures us that the sensory pleasures and cultural practices associated with eating animal products will not be disturbed. |

11. Promises to deliver the “delicious” taste and “mouth-watering juiciness and chew” of animal meat. 12. Images and videos showing the alternative products being cooked, eaten and enjoyed just like conventional animal products. |

1. Where quotation marks appear in the tables without a direct literary reference (e.g. [Name] [Year]), they denote direct quotations taken from the alternative protein narrative materials we analysed.

These promises reveal an interesting balancing act of simultaneously retaining and breaking away from different aspects associated with conventional animal foods (for further discussion, see Sexton, 2018). On the one hand we see promises of removing negative health and environmental impacts, food safety/security concerns, and moral harms. On the other, we see a very clear emphasis on the pleasurable and familiar eating practices of conventional animal foods being purposefully retained. The promise of these alternative proteins, then, is to preserve the perceived ‘good’ stuff of animal foods, and get rid of the ‘bad’. It is to offer the ultimate in good food: good for the planet, good for our health, good for animal welfare, and also, good to eat.

Biting back: Counter-narratives from the livestock sector

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these promises have prompted responses from those working in conventional livestock industries, ranging from big agribusinesses to proponents of alternative agricultural production (e.g. organic, slow food). A second aim of our paper was to examine and categorise these responses, an exercise which to our knowledge had not been attempted in recent studies on this activity. We conducted Google News searches between the years 2013-14 and 2017-18 to examine the different kinds of responses that have been documented across the media, as well as in policy and industry documents. Our preliminary findings led us to identify three main responses, or what we termed counter-narratives, which have been voiced by existing stakeholders across the livestock sector (mostly in Western countries):

|

TABLE 2 | Counter-narratives from existing livestock stakeholders |

||

|

|

Counter-narrative |

Description |

|

1. |

Not a serious threat |

The perception that the recent alternatives pose little market risk to conventional livestock industries due to a) scepticism over their technological capabilities being able to produce competitive and satisfying products; and b) anticipation of consumers rejecting their particular technoscientific methods. This response featured more in the earlier stages of the recent alternative protein activity. |

|

2. |

Not real food |

A response that challenges the ‘clean’ image cultivated by the recent alternative protein sector through highlighting the techno-scientific nature of their production techniques – specifically the use of biomedical methods, laboratories and in some cases genetic engineering. |

|

3. |

Not legally defined |

Somewhat related to the previous counter-narrative, more recent contestations have centred on what can and should be legally classified under the labels of ‘meat’, ‘milk’ and other animal-food terminology. Such disputes have worked across two characteristics of animal and animal-free products: (a) provenance (i.e. the raw materials and locations of production); and (b) production methods (e.g. conventional livestock rearing, tissue engineering and so on). |

One way to read the promises and counter-narratives surrounding these recent alternative proteins is to view them as a contest of hopes and anxieties over a range of different issues: from the welfare of the planet and its inhabitants (human and non-human), to the deep cultural values and enjoyment associated with animal farming and food products. It is also a contest over livelihoods, particularly within rural economies – more specifically, who will (not) be employed in the protein-food sector of the future, and in what kinds of jobs. Tied to these questions are yet more concerns over the future of rural landscapes. If livestock farming as we know it changes (or disappears), the ‘natural’ vistas of the countryside in places like the UK will almost certainly change with it. This could be in the form of increased conservation, with land spared from livestock farming given over to biodiversity and carbon mitigation schemes such as afforestation. It could also be in the form of increased urbanisation, privatisation and/or conversion to arable agriculture that could, in some scenarios, result in worse environmental and socioeconomic impacts than under some systems of livestock farming. More research is critically needed to think through these different scenarios.

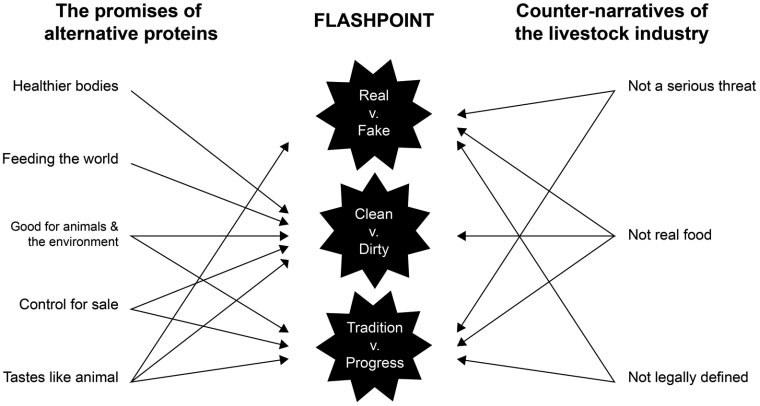

In our paper we wanted to go a step further in our analysis of these contestations. We posited that at the heart of this narrative battleground are three distinct yet interrelated binaries that have long characterised our hopes and fears about the foods we eat: ‘real’ vs ‘fake’, ‘clean’ vs ‘dirty’, and ‘tradition’ vs ‘progress’. So for example, when an alternative protein company promises a healthier and slaughter-free meat substitute, we can read this as promising a nutritionally and morally cleaner alternative than conventional meat. Conversely, when livestock producers contest the labelling of cell-based products as ‘meat’, they are contesting the realness of these products and also the values associated with more ‘traditional’ methods of production. We created this diagram to display how the different promises and counter-narratives can be seen to speak to the three binaries we identify:

What we hope to show through this diagram is that while the products being contested may seem new, these binaries reveal a much longer history of what has and continues to concern us about the foods we eat. Although focussed on animal foods specifically, we can read these narratives as reflective of a much broader and deeply historic contest over a) what different people think food ‘is’; b) what we think it should be; and c) our hopes and worries over what it is becoming under increased industrialisation and globalisation.

What we hope to show through this diagram is that while the products being contested may seem new, these binaries reveal a much longer history of what has and continues to concern us about the foods we eat. Although focussed on animal foods specifically, we can read these narratives as reflective of a much broader and deeply historic contest over a) what different people think food ‘is’; b) what we think it should be; and c) our hopes and worries over what it is becoming under increased industrialisation and globalisation.

Why does this matter?

The recent wave of alternative proteins has generated a significant amount of hype within public and corporate spheres. An overarching aim of our paper was to create a much-needed space for critically reflecting on this hype – in other words, to hold the promises made about these novel foods up to the light and examine what political, cultural and economic work their narratives are doing beyond the simple business of marketing. Part of this analysis was also to view the narratives as products of particular institutional and ideological contexts. Reflecting on the who, what and why helps to reveal that these narratives come laden with assumptions, cultural values, political histories and economic interests. It is important to acknowledge how promissory narratives are simultaneously a product and often a reinforcement of such contexts.

In the conclusion of the paper we highlight some specific points of concern that require further critical analysis; for example, the ways in which certain cultural representations around gender and meat-eating are (re)inforced through the promissory narratives we analysed, and how these might be problematic. We also highlighted the neo-colonial tendencies embedded in some of the promises to feed the world, and the recurring emphasis on technofixes as the means of doing so. These latter points reflect a longstanding and problematic narrative in which the Global North steps in as ‘saviours’ of the South through the means of Northern technology and science.

A key contribution of the paper is that it offers a more nuanced reading of the promissory and counter-narratives around recent alternative proteins than has sometimes been relayed in public discussions on this topic. It is not unusual for technology advocates to characterise cautionary responses as ‘anti-progress’ or as stemming from a stubborn rootedness in the past. Conversely, the hyper-positive stories of technofixers can often elicit distrust from audiences outside the world of Big Tech, and criticism that they are disconnected from the on-the-ground realities of sectors such as (in this case) agriculture. The value of our analysis is that it unpacks a shared set of values – albeit differing interpretations – at the heart of contemporary alternative protein debates. As such, what could be dismissed as anti-progress may on second reading actually reflect anxieties over the potential loss of cultural traditions, of rural communities, and of personal identities. What might be discredited as the shiny talk of tech advocates may actually reveal a hope for a future in which animals do not need to suffer, or even die, for food production. The binaries we discuss help to look past the novel features of this case study and situate it within a much longer history of our relationships with food and farming. In doing so, we hope to move forward from more polarised readings of ‘us versus them’ within these debates, and instead focus on the shared values, hopes and fears within current discussions of what a better (protein) food system could and should look like.

Do you have a comment on this blog? Use the comments form below or send a message to the FCRN's Google Group.

References

Brown, N., & Michael, M. (2003). A sociology of expectations: retrospecting prospects and prospecting retrospects. Technology analysis & strategic management, 15(1), 3-18.

Jönsson, E. (2016). Benevolent technotopias and hitherto unimaginable meats: Tracing the promises of in vitro meat. Social Studies of Science, 46(5), 725-748.

Mouat, M.J., & Prince, R. (2018). Cultured meat and cowless milk: on making markets for animal-free food. Journal of Cultural Economy, 11(4), 315-329.

Sexton, A.E. (2018). Eating for the post-Anthropocene: alternative proteins and the biopolitics of edibility. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(4), 585-600.

Stephens, N. (2013). Growing meat in laboratories: the promise, ontology, and ethical boundary-work of using muscle cells to make food. Configurations, 21(2), 159-181.

Stephens, N., Di Silvio, L., Dunsford, I., Ellis, M., Glencross, A., & Sexton, A. (2018). Bringing cultured meat to market: technical, socio-political, and regulatory challenges in cellular agriculture. Trends in food science & technology. 78, 155-166.

Comments (0)