This reflection about family farming in the UK – and some of the changes seen over 5 generations – was written in response to a conversation on social media, which led to the question: have we given up on the mixed family farm as a food producing entity?

About the author: Richard Bainbridge is a 3rd generation English farmer and retired Methodist Minister.

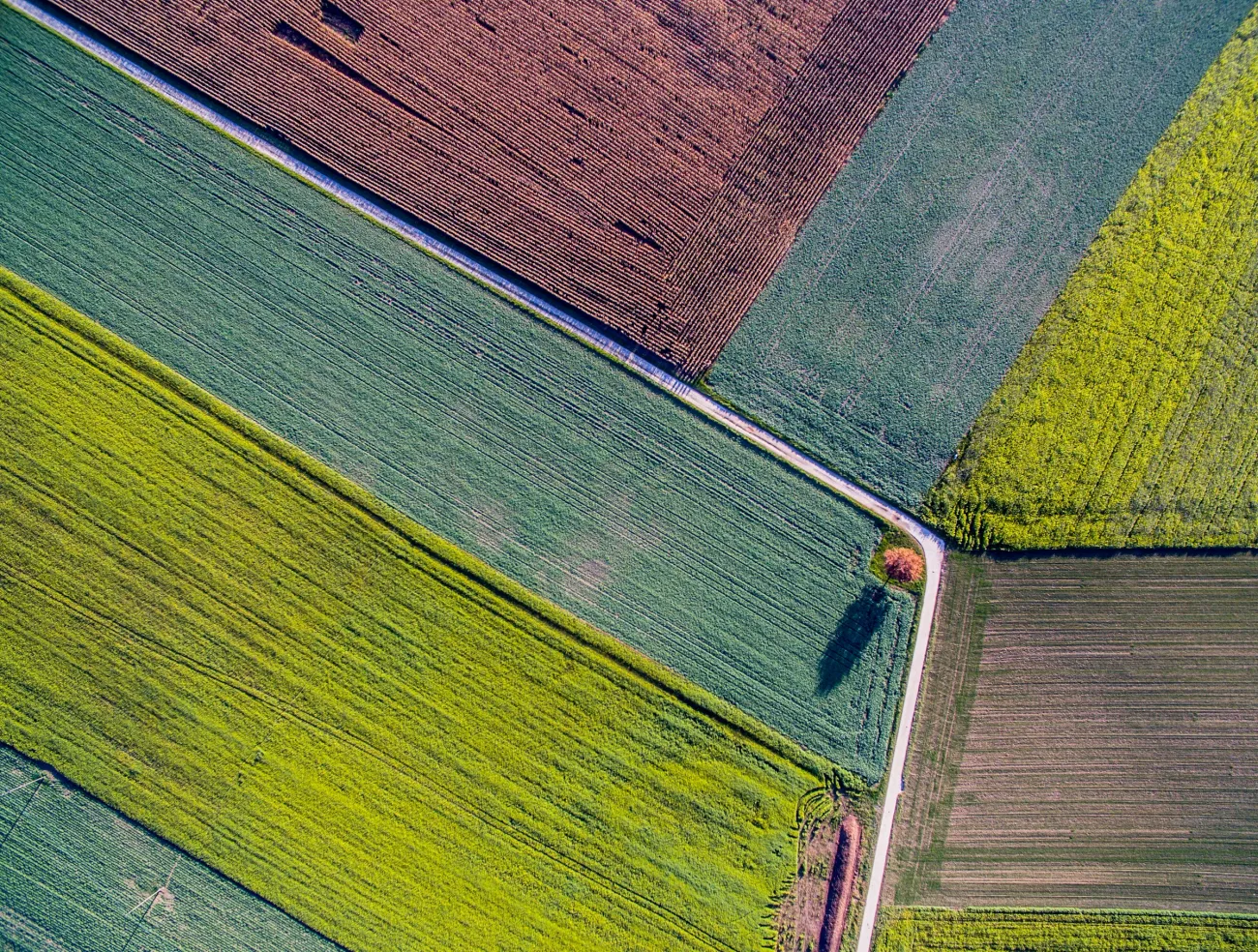

Image: A family farm in Northumberland, by Richard Bainbridge

Having attained State Pension age, I find myself with a clear view of 5 generations of my family, effectively a century or more of family life.

My paternal grandfather survived the Great War. After the war my grandparents ran several businesses in a tiny village in an obscure corner of North East England. Grandma ran the village shop and Post Office, Grandad was postman and ran a one man taxi/light haulage business. They also found time to run a small farm on the few acres they owned.

National agricultural policy was all about growing more, ‘grow 2 blades of grass where there was 1 before’.

This was the farm my father inherited and on which I was brought up. It was the 1950s. The post war Green Revolution was in full swing. National agricultural policy was all about growing more, ‘grow 2 blades of grass where there was 1 before’ was the mantra. Farmers found they had a whole new box of shiny tools to play with – artificial fertilisers, chemical sprays, new breeds of livestock and crops, new techniques of intensive production and, ever larger farm machinery.

Dad rode that wave for all it was worth. Running free range poultry, he had seen them looking wet and miserable in winter, seen the havoc a predatory fox could wreak. So when battery cages were introduced he took the opportunity to make the most of his small acreage by building up a large caged laying flock. He was proud of what he achieved and would happily show visitors around the farm to see his ‘happy’ hens.

The hens weren’t for me. We lived in the uplands and I wanted to farm sheep and beef cattle. I had 3 brothers and eventually we were all able to begin farming on our own account. From 1981 my wife and I ran a small hill farm on which we brought up a family of 4. We were still enjoying the green revolution, MAFF (the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food) grants were available to drain and improve land. But the farm was to be our home for only 15 years when in 1996 I sold up to pursue a vocation in the Church.

However, it is easier for the family to leave the farm than for farming to leave the family. And now my eldest daughter, her husband and children are farming whilst I am the one who tries to support them with advice and some practical help. Oh, and I’m also the one who worries about their future.

5 generations, 100+ years. Much has changed for family farms and food systems, but some common themes remain. Farming is not the rural idyll that it must sometimes appear to those caught up in the daily commute to work in a soulless office or production plant. Farming is a tough gig and places huge pressures on family life. There’s the weather for a start. And the inconvenient fact that you live on the job and are on call 24/7. For the smaller farms there are issues of isolation but the by far the biggest challenge is making the thing pay.

Farming is the only business that buys retail and sells wholesale.

It is said that farming is the only business that buys retail and sells wholesale. Farmers are squeezed between big ag on the supply side and supermarkets when they sell. And the smaller family farm has a struggle to even get noticed. Basic economics mean such farm businesses will always be weak buyers and sellers. When he began farming my father ran a small herd of dairy cows, as did almost every other farmer in the area. Now there is just one herd left. When bulk tank collections were introduced the more milk you produced, the better the price. It makes economic sense for the dairy company to fill its tanker at 4 farms rather than having to visit 24.

So, family farms had to find other ways to survive. Partners would work off the farm, perhaps. In the early days B&B became popular in some areas. Then, if suitable buildings were available, they could be turned into holiday accommodation. Farm shops sprang up. Opening the farm to visitors could bring in income (and problems). Diversification was now the name of the game.

They feed the nation, that, surely, has to be a good thing, right?

Whatever problems family farms face there are a couple of things that help sustain those families through difficult times. The first is the feeling of being part of a community. Farmers know that they are a minority and that feeling of being set apart from the urban majority creates bonds of identity and community. The second reason why farming families keep going through difficult times is a sense that what they do is of value. They feed the nation, that, surely, has to be a good thing, right?

Well, maybe not. Polluted waterways, sheep wrecked moorland, methane belching bovines, biodiversity collapse. The rhetoric has been ramped up in recent times led by the voices of urban polemicists with books to sell. To farming families struggling to survive it feels that the finger is always pointed at them.

Confidence is low. In the wake of Brexit, the direction of Government policy is causing concern in farming communities. Financial support for farming is changing and while most farmers welcome the shift towards a greater focus on environmental issues, there remains little certainty over what that means for individual farms as the clock ticks down. The only certainty being that whatever money is available there will be less of it.

Also changing are the trade deals the Government is able to make with other nations and trading blocks. As Government pursues an electorate pleasing cheap food policy, farmers fear that they will be undercut by cheaper produce from abroad with dubious provenance and welfare standards.

Faced with all of these, plus calls for rewilding, right to roam, eat no/less meat, plant trees, grow wildflowers, offset carbon and cuddle a badger, it is no wonder that farming families find their children deciding against following in Mam and Dad’s footsteps and that the average age of farmers continues to rise.

There is a social element to this. Farming families knit rural communities together. Their children attend local schools, they are more likely to buy and sell locally than larger companies, they contribute to a sense of local identity and community cohesion. They also have a wealth of local knowledge, they know the land and their local climate. They are proud of the area in which they live and want to see it thrive. And, on the whole, for no one group of people is perfect, they care about the future.

Wouldn’t it be ironic if, as we struggled to deal with climate change, collapsing biodiversity and a food system that is barely fit for purpose, we allowed to go to the wall some of the very people who could deliver changes that are needed in ways that are holistic, effective and long lasting?

We are told we are living through the 6th mass extinction. Are family farms going to be a part of that and, if so, does it even matter? Will my daughter and son-in-law’s generation be the final generation of authentic family farmers? I firmly believe it does matter. Wouldn’t it be ironic if, as we struggled to deal with climate change, collapsing biodiversity and a food system that is barely fit for purpose, we allowed to go to the wall some of the very people who could deliver changes that are needed in ways that are holistic, effective and long lasting.

Some of those who are calling for radical change in our farming practices are already calling for a ‘just transition’ to move people out of what they perceive to be ways of farming that need to end. Such calls are patronising, offensive and threatening. Farming is a way of life, an identity, a reason to be proud. Farming families are the backbone and the lifeblood of the countryside, they deserve to be valued, respected and encouraged, not transitioned, justly or otherwise.

Comments (0)