In this piece, Hatim Rijal and Marwa Akola reflect on the challenges facing Sudan’s food system. They explain the pressures facing different types of agriculture and forestry in Sudan, and explore the potential of agroforestry, specifically alley cropping systems, to provide food while also meeting environmental and social goals.

About the authors: Hatim Rijal (MSc. in Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development) is the fundraising officer of the Deriba Center for Environmental Studies (DCES), a Forest Inspector at Forests National Corporation, South Darfur State, and a Co-founder of Sudan Youth Organization on Climate Change (SYOCC). Marwa Akola (MSc. in Nutrition and dietetics) is a clinical dietitian nutritionist, a lecturer in the School of Health Sciences at Ahfad University for Women (AUW), the head of the Research and Studies Unit in DCES, and was recently assigned as a program coordinator for the Public Health Training and Research Unit (PHTRU) in AUW.

Introduction

Sudan, a country with an area of about 1.88 million km² and located in northeast Africa, is bordered by seven countries – Central African Republic, Chad, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, and South Sudan. It used to be the largest in Africa in terms of size, but after South Sudan’s secession in 2011, the area was reduced by 24.7% which now makes it the third largest country in Africa after Algeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sudan is known as a country with a highly diverse vegetation cover, agricultural production, and rich ecological zones. According to the African Development Bank (2020)1. However, although the country is endowed with a variety of natural resources both on land and beneath its surface along with its human capital, the recent problems the agricultural sector has faced, in addition to the negative impact of many combined factors on the country, have slowed down its development, created a livelihood crisis, increased its hunger profile and placed it in the category of least developed countries (LDC) according to the United Nations2.

A map shows the location of the republic of Sudan. Image credit: Anthony Beck 2022, Pexels, Pexels Licence.

Also, the clear position of the international society where international aid was suspended due to political turmoil, put Sudan in an urgent need for solutions and actions to support its food system shifting toward a sustainable one and to eventually secure enough food for its own people. In this article, we highlight the challenges our food production system is facing and present the different views of stakeholders on the main causes, current actions, and possible solutions focusing on the synergies and trade-offs between agriculture, forestry, and agroforestry.

The article is written by two Deriba Center for Environmental Studies (DCES) members. Hatim Rijal (MSc. in Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development) is the fundraising officer and an environmentalist with six years of experience in the Forestry sector. He is also a Forest Inspector at Forests National Corporation, South Darfur State, and a Co-founder of Sudan Youth Organization on Climate Change (SYOCC). Marwa Akola (MSc. in Nutrition and dietetics) has more than four years of experience as a clinical dietitian nutritionist and is a lecturer in the School of Health Sciences at Ahfad University for Women (AUW). Marwa is also the head of the Research and Studies Unit in DCES, an activist and was recently assigned as a program coordinator for the Public Health Training and Research Unit (PHTRU) in AUW. Marwa has been working in rural communities with high rates of unemployment, household food insecurity, and severely malnourished children.

The reason behind our interest in this topic is that both of us belong to indigenous tribes living in poor rural communities. Our experience of running community projects in combination with the knowledge we have gained from our Masters programmes, has motivated us to pose critical questions about the current situation facing Sudan’s food system, such as: “Although rural communities depend on natural resources for survival and practice agriculture on some of the most fertile land in Africa, why are our people still suffering from hunger and poverty? Where are the gaps in the existing policies that hinder modernising our food system? What are the solutions? What do different stakeholders think?”. Since we both believe in the power of information to drive a sustainable change, we think it’s time for everyone to get involved in debating the validity and future consequences of the current food production system policies and practices in Sudan.

In the next sections, we will first introduce the types of food production systems in Sudan and the current status and challenges facing them. Then, we will explore the perceptions that stakeholders have about securing food from both the agriculture and forestry sectors, and to what extent they are adopting sustainable food systems approaches. Finally, we will look at agroforestry – an approach that combines agriculture with forestry – and try to answer the question “Can agroforestry support the shift to a sustainable local food system?” by discussing its benefits and drawbacks.

An overview of Sudan’s food system

The role the agricultural sector plays in fighting hunger and providing employment opportunities in rural areas is vital. This sector alone produces 32% of the nation's GDP3. Crop and animal production, including the informal economy, employs around 80% of the working population. As a result, the bulk of the nation's population is reliant on natural resources for a means of subsistence.

The majority of Sudan's land area – roughly 292 million feddans, or 122.6 million hectares – is classified as arable land. Overall, the food production system in Sudan can be classified into three sub-sectors: (1) irrigated, (2) semi-mechanised rainfed, and (3) agro-pastoral traditional rain-fed. Rain-fed agriculture is Sudan’s main traditional farming system and provides most of the food for rural communities. According to the Ministry of Finance and National Economy (2011) 4, rain-fed agriculture contributes to roughly 60% of the nation's output of food grains and employs more than 60% of the agricultural workforce in rural areas. It accounts for 29.5 million feddans (12.4 million hectares) representing 96.1% of the total area planted in grains5. About 8.3 million feddans (3.5 million hectares) of land are irrigated and used to cultivate various crops, primarily sorghum, millet, wheat, cotton, ground nuts, sesame, sugar cane, and vegetables such as potato, onion, okra, and tomato. A vast region of 15.0 million feddan (6.7 million hectares) across many states is used for semi-mechanised rainfed agriculture6. With sorghum making up over 80% of the farmed area, it might be said that it serves as the nation's grain store. Sesame, sunflowers, millet, and cotton are examples of other crops grown in this region.

Livestock is raised mainly by pastoral and agro-pastoral groups. Herd sizes can range from < 50 head of cattle to several thousand per household. Pastoral herds are typically semi-nomadic, as seen in western Sudan and the southern Blue Nile, where customary herd movements take place between grazing regions during the rainy and dry seasons. Rich grazing is possible during the wet season, and pasture and water are also available. Household economies in the Butana region (central-eastern Sudan) are based on an agro-pastoralist method of production, which involves the raising of both livestock (goats, sheep, cattle, and camels), and crops (sorghum)7. The proportion of each type of animal in the herd is determined by its location within this significant grazing area and pastoralist mobility patterns, as well as by the proportional value of livestock production and cultivation to each household. This contrasts with the pastoral production systems in western Sudan where tribes are specialist camel (Abbala) or cow (Baggara) owners and some minimal arable farming is also practised to satisfy all or some of the family grain needs. Large numbers of animals, mainly camels and sheep, are shipped to Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and other Arab nations. Recently, beef has also been sold to these nations8.

Cattle grazing at Deriba Lake in Jabell Marra, Central Darfur State, Sudan. Image credits: © AlaaEldein Yousif 2020 – Environmental Activist and CEO of DCES.

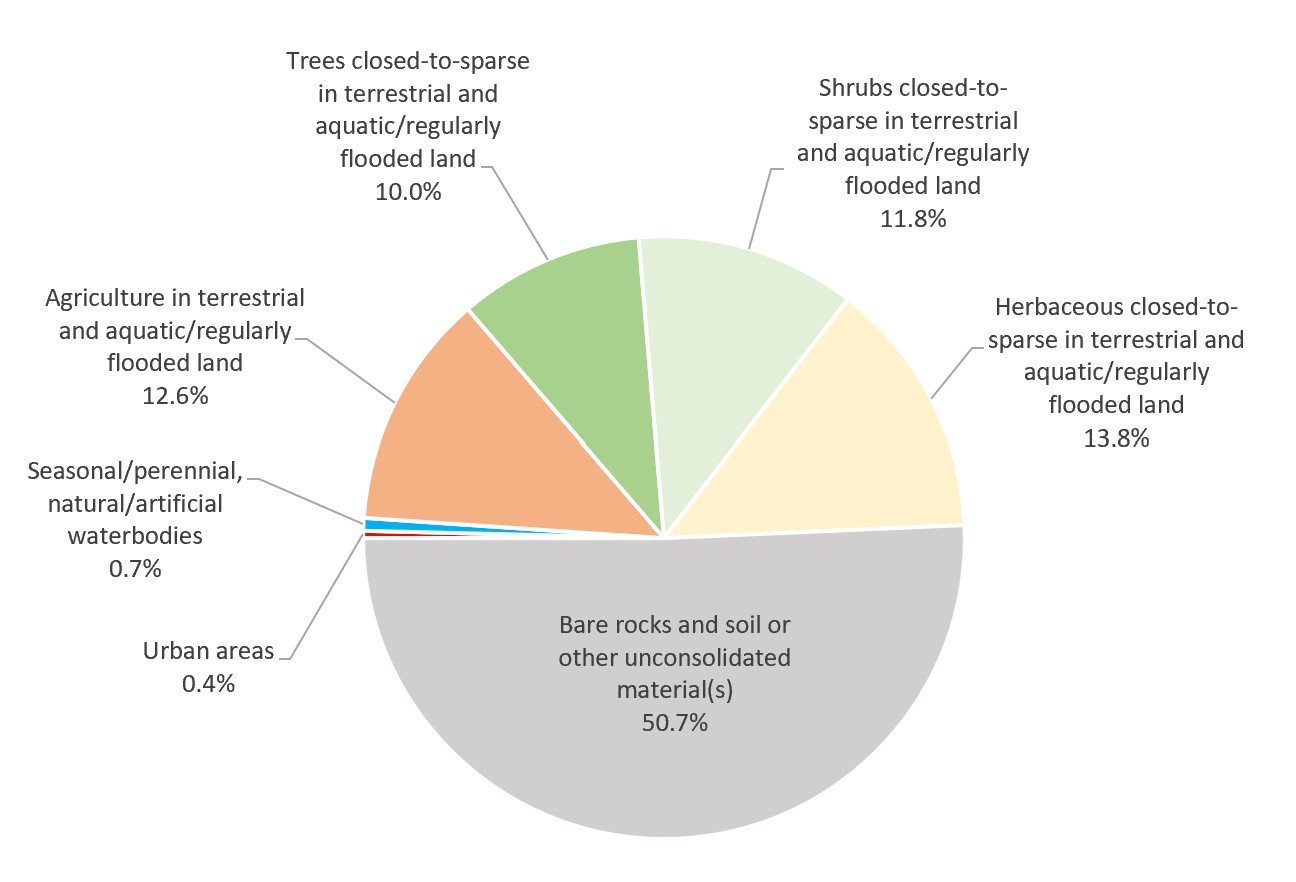

There is a notable lack of accurate data on forests in Sudan and only ad hoc surveys can be used to infer information on the size of Sudan's forests and rangelands. According to the 2012 land cover map created by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 10% of the country is covered with trees9. About 51% of South Kordofan is covered by trees, making up more than a third of all the trees in Sudan10. The massive spread of partially mechanised farming is mostly to blame for the low tree coverage in the states of Blue Nile, Kassala, White Nile, and Gedaref. Dinder National Park, the biggest protected area in the nation, is the reason Sennar state has wider coverage. Nevertheless, a study by Gafar (2013) found that there are 714 km2 or 17 million feddans of protected forest reserves in Sudan. The states of West Darfur, South Darfur, Gedaref, Blue Nile, and White Nile contain most of the reserves. 70.2% of the country’s forests are owned by the government and managed by the Forests National Corporation. 28.2% are owned by Gum Arabic producers, while 0.2% are owned by individuals. Forests listed under the names of private enterprises and communities account for 0.8% and 0.6%, respectively. According to estimates, Sudan has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, 2.4% each year.

Figure 1: National land cover by type in Sudan. Source: FAO (2012), The Land Cover Atlas of Sudan.

Current problems facing Sudan’s food system and causing hunger

When assessing Sudan’s food system and its food security situation, it is important to consider all factors that negatively affect it.

“[In] terms of availability of arable land and different water resources, the country has the potential to become the main food provider for Africa and the Middle East.” (Mahgoub, 2014)

Unfortunately, Sudan is still struggling in defining basic concepts, current drivers, and influences related to its agricultural and forestry productions, and its contribution to successfully shift toward a secured food production system. In fact, with many countries trying to modernise their food systems to meet their peoples’ food needs, people in Sudan are still discussing the concept of food and nutrition insecurity without an intention to modernise the food systems, and very little is done under the new concept of the sustainable food system – we have not yet adapted any tools and indicators or identified parameters to measure the change. The reason behind this noticeable delay is the crucial combined impact of many intrinsic shocks and stressors.

The first stressor is the political upheavals Sudan has experienced through numerous political regimes ranging from civil government and multiparty systems, to military government and one-party systems. It has impacted the country’s development strategies and resulted in periodic food shortages during the last few decades. According to the IPC (2022)11, almost 9.6 million people across Sudan, or about 21% of the country’s population, were highly food insecure and classified in Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse in the period from April to May 2022. The areas most affected by food insecurity are the ones suffering the most from long years of civil war and current armed conflicts including Darfur Region, South Kordofan, the Blue Nile States and before that South Sudan. The political turmoil in these fragile areas and other different areas around Sudan has led to population displacements into areas with already limited resources. For instance, in 2021, The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) reported that more than 430,000 people were displaced, mostly in Darfur, from January to October which is the highest number of civilians fleeing violence since the height of Darfur’s conflict years ago. As a result, a vicious cycle of poverty and conflicts over natural resources and hunger was created12.

Another stressor is environmental crises. Climate change impacts, mainly desertification, water scarcity, severe drought and floods, are our biggest threats. For example, areas affected by floods during the last seasonal rains (heavy rains usually fall in Sudan between May and October) included North Kordofan, Gezira, South Kordofan, South Darfur, and River Nile. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the government’s Humanitarian Aid Commission, more than 136,000 people have been affected by the floods in 2022.

“The number of people and localities affected by the seasonal rains as of August 14 had “doubled” compared with the same period last year.” the UN said (Al Jazeera news, 2022).

Furthermore, COVID-19, poor governance, lack of expertise, challenges with food distribution, and mismanagement of the national budget and land use by the authorities and policymakers are other current problems causing hunger – not forgetting the economic downturn – including the interruption of natural and human resources and the known corruption which has led to higher than usual levels of acute food insecurity in Sudan.

These crises have led to poor harvests, which have significantly reduced the accessibility, affordability, and availability of food. During the 2021-2022 agricultural season, total grain production amounted to 5.1 million tonnes, 37% lower than the previous season of 8.1 million tonnes13.

According to the FAO Humanitarian Response Plan 2022 for Sudan, 10.9 million people (out of a total population of 46.1 million) were expected to need life-sustaining support in 202214. That number is increasing: the Sudan Situation Report, 12 February 2023 of OCHA15, reported that 15.8 million people are in need of life-sustaining support in 2023, the highest number in the past decade.

We believe that this whole scenario Sudan is currently experiencing predicts that the demand for life-sustaining support will keep rising, especially with the current increase of local prices of wheat to over US$ 550 per ton due to the Russian-Ukrainian crisis – 180% higher compared to the same period in 202116.

"It is known that Sudan gets more than 90% of its needs of wheat from Russia and Ukraine," said Abdul-Khaliq Mahjoub, a Sudanese economic expert in an interview with Xinhua.

The Sudanese agricultural system is characterised by a monoculture system, whereby a single product type is cultivated over a small piece of land, be it semi-mechanised or traditional, with an exception for the large government mechanised schemes. Moreover, the government's plans were solely focused on mass expansion to produce more, without considering the negative impacts of such practices on the environment. This approach has been criticised by environmentalists and academics, who see that long term environmental issues can be caused by this policy. What they propose, instead, is to adopt a holistic approach to producing food while also preserving the environment.

Controversy over solutions: agriculture or forestry?

There have been several solutions proposed to improve Sudan’s food system, such as expanding and intensifying agricultural production, protecting forests, and combining both through an agroforestry system. We discuss each option in more detail below.

Expanding and intensifying agricultural production

It is expected that Sudan's population will continue to increase steadily by 2.4% per year in the coming decade or so. This puts great pressure on the already limited resources to adequately meet increased demand for food and fibre. The traditional rain-fed sector's main issue is population pressure, which is causing unsustainable rates of land exploitation and contributing to deforestation in Sudan as well. This problem is a lost opportunity since traditional farmers, in their quest for immediate food security, are burning and removing trees that would yield considerably higher returns as agroforestry plantings than as short-term crops. Due to hunger issues, high-value timber trees are being burned in different area just to make room for a few years of low-intensity maize farming17. When population density is low, traditional rain-fed agriculture has been shown to be reliable and self-sufficient. This balance is currently being broken by demographic, political, and technical issues, and Sudan is witnessing a breakdown in longstanding patterns and an unsustainable intensification of agriculture in most of its sub-sectors. Policymakers often see agricultural expansion as a way to meet food security and to grow the country’s economy. In doing this, however, they wish to fight resource degradation through expanding agricultural land into forest lands.

Protecting forests

Many literatures reveal the advantages of forests for food security in different communities, which include hunting, grazing, forest foods including tree leaves, nuts, tubers, wild fruits and herbs, and tree bark for medicinal purposes, besides the Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFPs) such as honey and gum Arabic18. South Kordofan, South Darfur, Jebel Marra, Southern Blue Nile, and regions along the Nile and its tributaries are the significant production areas for NWFPs. But with the forested area decreasing over time – for example, between 2011 and 2020 it decreased from 10.8% to 9.8%19 – concerns about the future of the NWFPs in Sudan are increasing. Currently, we are witnessing lower rates of production, harvest quantities, uses, and value marketing.

Images: Some of the indigenous fruits that can be found in Sudan. For further images and information about other fruits of Sudan, see Magid (2015).

Fruit of Adansonia digitata (also known as baobab/gongoles/balboa). Image credits: nike159, Baobab tree fruit, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence.

Fruit of Hyphaene thebaica (doum palm). Image credit: sarangib, Palm fruit, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence.

Fruit and flower of Grewia tenax (also known as godeim in Sudan). Image credit: Lalithamba, Grewia_tenax_(Forssk.)Fiori, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons — Attribution 2.0 Generic — CC BY 2.0.

There are different opinions regarding the main causes of forest deterioration. On one hand, many environmental activists believe that displacement and overpopulation are the reasons for the growing demand for agricultural land and forest products. This belief aligns with leading reports which concluded that other countries’ food systems face a similar crisis as in Sudan. This assumption was derived due to the increased conflicts between nomadic and settled communities over natural resources that developed into ethnic and tribal wars threatening national security20.

On the other hand, many economists and academic experts blamed the government for the deteriorating situation; they argue that its policies have led to improper land use practices, such as shifting cultivation that has been practised on progressively shorter cycles, frequent and uncontrolled bushfires, lack of soil conservation measures, uncontrolled livestock grazing, and farming on marginal lands. Our debate here is leaning towards the second point of view, where the sector is witnessing a massive dropout from smallholders and local farmers due to the huge taxes the government has applied, and due to government policies such as permitting the large-scale agricultural land acquisition that allowed private companies and governments such as China and Gulf countries to dominate the sector and to have strong control over the prices of machines, rented land, salaries, crops, and other variables. Therefore, many environmental activists, including ourselves, are calling for forest protection.

We believe the Sudanese are more aware and concerned about the government's policies and poor governance of land and budget, than about the impact of the environmental crisis. These concerns stem from the interplay of power dynamics of who should have the ultimate say and control over natural resources between the different ministries. However, looking at the whole picture including the historical as well as the current degrading situation, it looks difficult to increase dependency on forest production at the moment.

A form of environmental crisis (deforestation) made by local citizens in Radom National Park in Southern Darfur State, Sudan. Photo credit © AlaaEldein Yousif 2020 – Environmental Activist and CEO of DCES.

By 2064, Sudan is expected to have 100 million inhabitants. The annual rate of population growth is over 1 million people. As a result, the demand for food is rising rapidly, placing more strain on the agricultural sector and leading to increased consumption of land and water. The continuous conflicts and effects of the climate crisis are making the situation worse. The Ministry of Agriculture bases its case on this data and maintains that there is a pressing need to feed the expanding population; nonetheless, the agricultural landscape has grown increasingly constrained. As a result, people view forest regions as trustworthy suppliers of land that can feed them.

Since Sudan is one of the three nations that can help ensure international food security owing to its vast and fertile agricultural lands, the question of can we depend on agricultural production alone to achieve local or national food security? will always be asked. Prior to South Sudan’s separation, Sudan had an estimated 86 million hectares of fertile arable land that could be farmed – an area that has been reduced by 35% since the secession21. The assumption that the agricultural sector may significantly contribute to achieving food security, can only turn into fact if we succeed in expanding food production in rural regions in a sustainable way that creates job opportunities for the majority.

However, the Forests National Corporation and environmentalists share different perspectives on the situation. They contend that forests serve as a safeguard against environmental threats that Sudan is already facing. Additionally, they cite the many benefits that forests contribute to food security. But such services have faced increasing encroachment from agriculture, urbanisation, and unsustainable wood fuel extraction for several decades. The lack of integrated land use coordination across institutions has resulted in uncontrolled land use changes and the conversion of vast forest tracts into agricultural areas over the past 40 years. Therefore, its preservation should receive a lot of attention.

Nonetheless, there is a third view that strives to bridge the gap between the two sides. It considers the situation as one of competing interests and policy incoherence and, as a result, adopts a middle ground position. According to this point of view, agriculture and forestry can coexist along with one another in a mixed system termed agroforestry, whereby crops can be grown alongside trees. This method can assist both agriculture and forestry while achieving their mutual goals.

Is agroforestry a solution?

ICRAF22defines Agroforestry as the interaction between agriculture and trees, particularly the utilisation of trees for agricultural purposes. The production of trees for timber and other commercial purposes, the production of a diverse, sufficient supply of nutritious foods to meet both global demand and the needs of the producers themselves, and the protection of the natural environment so that it can continue to provide resources and environmental services to meet the needs of both the current generation and future generations, are part of the requirements this system is attempting to balance.

Agroforestry is a sustainable technique of land management that combines the production of crops and animals and/or plants from forests on the same piece of land. In order to increase the overall yield of land through the production of a variety of crops, raise the level of living in the area, and enhance or protect the environment, agroforestry employs management approaches that are compatible with the cultural practices of the local community.

Forest rehabilitation (afforestation) through some type of agroforestry plantation with seeds and seedlings in the reserved forest in Nyala - Southern Darfur State. This type of agroforestry is named “Tungya” in the local language. Photo credit © Hatim Rijal 2020 - Forest Inspector.

Although agroforestry has many different types, alley cropping (intercropping) systems are our focus in this article, and in particular, we are going to discuss the importance of Acacia Senegal and Acacia Seyal trees for agroforestry systems. This system is widely spread in Sudan, especially within the rain-fed agriculture sub-sector and within lands that are managed by governmental institutions in their efforts to rehabilitate the degraded forests in the country. The alley cropping system has been proven to have a plethora of benefits that align with the local food system. For instance, a study by Xu et al., (2019) found that alley cropping enables the farmer to utilise the resources at hand efficiently and provide greater benefits. Designing this system requires selecting appropriate crops to grow together and reducing crop and tree competition23.

Some believe that we should roughly double our global food production if we are to attain global food security24. The prevalent strategy for reaching this goal is conventional agriculture, but it has also seriously harmed the environment and society. According to the sustainable development goals, it is generally agreed that we now require agriculture that can "multi-functionally" boost food production while also advancing social and environmental goals (SDGs). Additionally, farming needs to develop greater resistance to a variety of threats, such as soil erosion and market volatility, all of which are likely to make the hunger problem worse.

Agroforestry systems (in particular, alley cropping systems) can boost yield while simultaneously advancing several SDGs, particularly for the small-scale farmers in developing countries who are at the heart of the SDG framework. Agroforestry also improves farm livelihoods and crop resilience, particularly for the most vulnerable food producers. The introduction of more multifunctional options has been hampered by the natural dominance of conventional yield-enhancement tactics25.

It is generally agreed that agroforestry can provide many services for both people and the planet. However, its ability to feed a projected 9 billion people in the world by 2050 is questionable. Agroforestry, like any other system, has its pros and cons and it cannot provide the full answer alone unless it is joined with other options. Supporters of this system often cite many pieces of scientific evidence supporting the benefits that this system can bring in theory. However, what they might miss is that there is no “one size fits all”, as this system might work well in certain areas whereas it might be faced with huge challenges in others. Therefore, a balanced view is needed.

“Agroforestry is one of the vital vegetation recovery systems for countries with degraded forests like Sudan. I believe that it can easily support the sustainability of natural resources and forests (through producing non-wood forest products) by conserving land fertility. Which will support the livelihood of the local population and achieve food security.” Alaaeldein Yousif, an environmentalist and a founder of DCES.

It is worth noting that agroforestry system implementation encounters major difficulties such as land tenure, especially in Sudan’s context. The issue has historical roots since the country was ruled by tribal systems which are still persistent today in some parts of the country, whereby the head chief is the one responsible for distributing and assigning the lands.

Numerous goods and services are produced by agroforestry operations. Trees can give resources for meeting social obligations as well as benefits including food, shelter, energy, medicine, cash income (through investing and saving money), raw materials for crafts, and fodder. Also, this system can offer other benefits, such as improving the soil's fertility for crop growth. In Sudan, these goods and services are generated from Gum Arabic gardens – known locally as the Tungya system – whereby an Acacia Senegal tree is planted in a piece of land with agricultural crops, such as millet or sorghum. Below are the details of this system.

Gum garden management

Gum acacia trees in Bahar Alarab locality, Sudan. These types of trees are named Acacia Senegal (hashab) and Acacia Seyal var. seyal (talha). Photo credit © Ahmed Younis 2021-PhD student.

Gum Arabic is a NWFP of the genus Acacia tree, well established in the local and world markets, and has been an article of commerce for some 4000 years. Its importance lies in the fact that it is a community-based resource, providing income to citizens. In addition to gum Arabic production, the gum tree is essentially an arid zone species having even greater importance in the protection and improvement of soils, in checking desert encroachment, and more importantly in facilitating further periods of agricultural cropping in an already depleted and fragile environment.

The people living within the gum area of Sudan are either settled agriculturists, who cultivate the land to produce subsistence crops, or nomads who use the land for grazing. The land is owned by the state and used as a common resource, but individuals have acquired rights (usufruct) over smallholdings to the extent that they are considered to be the rightful owners of such lands. They are entitled to the income from such lands whether they work it or lease it out.

Besides the gum, there are several products obtained from the agroforestry system of the gum gardens, including sesame, sorghum, groundnuts, and others. Good practices in agroforestry systems in the gum belt zone are accommodated in different types of land use related to their methods of establishment, stages of development, and degree of human interventions that contributed to their formation and development. The homestead cultivation system developed and managed in the home garden, called “the Jubraka”, constitutes the first cycle. Some of the cereals that include maize and some horticultural crops are cultivated on a small scale on a small piece of land at the homestead. The “Jubraka” system is a common practice in western Sudan and is usually found throughout the gum belt, as an integral part of the traditional subsistence rain-fed farming. Women are responsible managers of the Jubraka because of their presence at home.

There are no accurate statistics yet to display the extent to which agroforestry contributes to food production or other benefits. Nonetheless, agroforestry practices applied in different ecosystems contribute to sustaining agricultural yields, stabilising the local communities, and improving their livelihoods.

Like natural ecosystems, agroforestry systems can be extremely diverse. What functions well on one farm might not function well on another. It might be challenging to forecast the complex interactions between the various species of trees, animals, and crops. Appropriate knowledge, careful planning, and routine tree maintenance are necessary for a successful agroforestry system. It can be inconvenient for some farmers if there are trees or shrubs growing alongside the crops because this prevents a farm from being fully mechanised.

Personal reflections and conclusions

While we lean towards the view of finding a balance between the agricultural system and the environment, what formed Hatim’s assumption was more of a personal experience from his childhood, as farmers in his region used to adopt agroforestry (Tungya). During this small piece of work, we could look at the situation from each other's perspectives and form a full idea about it. Hatim could reflect on the issues surrounding forestry and agriculture productions and Marwa reflected on her experiences from working with under-crisis communities and shared her lessons learned from her trips between both developed and developing countries. We both agree that agroforestry, if implemented correctly taking into consideration the location and cultural contexts, would provide the benefits that are often ascribed to it. However, looking at Sudan's context, the system has not been implemented properly, as there has been a vacuum between science, policy, and application on the ground.

In conclusion, we believe that we need more dialogues and debates involving different stakeholders and focusing on the current challenges facing Sudan's food production system, its progress, and solutions to overcome it. In addition, we need joint actions that define and distribute authorisation among institutions and search for the best methods to monitor and evaluate the contributions of each sector toward decreasing hunger in Sudan.

Many proposed questions like What is our best solution to shift Sudan’s food system? can be answered and discussed by conducting delegations’ sessions, research, training workshops, webinars, and much more. In the end, we think that the best form of sharing opinions and solutions is through creating a platform like TABLE that gives space to reflect, discuss, explore, and to give a full idea on the current situation.

Comments (0)