This paper adds to the literature on modelling agricultural land-use demand in 2050 given a growing global population, climate change-induced changes in yields, and projections for as-yet unrealised technological improvements. The main innovation of this study is to constrain the amount of dietary change that can be included in the model. Consequently, this model includes much more regional dietary variation than do other such projections, and much higher ASF consumption than many. The authors find that, contrary to previous studies, several regions cannot achieve food security without expanding agricultural land use. In particular, more pasture land is needed, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In a wider group of regions, producing sufficient food without increasing agricultural land use only appears possible if we assume an optimistic scenario for increasing yields

Summary

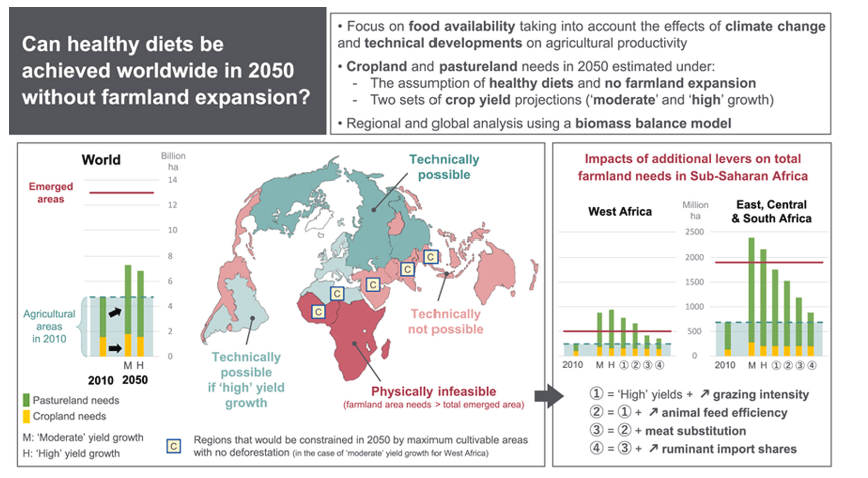

This paper assesses the possibility of achieving food availability to the world by 2050 by constraining the amount of dietary change that can be included in its model and assuming no farmland expansion. Consequently, this model includes much more regional dietary variation than do previous projections, and much higher ASF consumption than many dietary guidelines. The use of ‘healthy’ diets, in the article, was inspired by ‘healthy’ diet recommendations in the Agrimonde-Terra foresight study (summarised in Le Mouël et al., 2018 amongst other scenarios and models). The authors argue that this method provides more regionally specific recommendations than other model-based studies for two reasons. Firstly this study allows for on average higher levels of meat consumption than do other sustainability-oriented studies which seek to model healthy diets, on the grounds that higher levels are more realistic; and second, it allows for regional variation in levels of meat consumption, taking as its cue existing differences in dietary patterns. For example in 2050 animal product intakes in the Americas, Europe and China are assumed to remain substantially higher (accounting for around 20% of calorie intakes) than in India, many other parts of Asia and parts of Africa, where they are assumed to account for about 12% of calorie intakes (see SM3 in the supplementary material. As regards to calorie intakes, 'healthy’ diets as defined by this paper in 2050 correspond to a daily calorie intake of 2,750-3,000 kcal per person. This is notably higher compared to other "healthy diet" recommendations such as Röös et al, 2017 where for example 2750-3000 kcal per person is close to a business-as-usual case and a ‘healthy diet’ scenario sets the recommendation at 2500 kcal per person. It is unclear if the authors intended to reference caloric availability or supply rather than actual intake

A key finding is that it is impossible to secure healthy diets in 2050 without farmland expansion in India, the rest of Asia, Near- and Middle-East countries, North Africa, and in particular sub-Saharan Africa due primarily to pastureland needs. The authors suggest that the more regionalised healthy diet recommendations are more realistic than those that form the basis of earlier studies, and as a result those earlier studies underestimated the extent to which farmland - and specially pastureland - expansion is likely to be needed in 2050

Image 1: Forslund et al. (2023). Visual abstract highlighting global feasibility of securing healthy diets assuming no farmland expansion.

This study contributes to global nutrition debates which have previously found only a limited need for farmland expansion to achieve healthy diets. They assess the possibility of securing food availability with an assumption of no farmland expansion. The authors highlight a key gap in previous literature which has underestimated farmland expansion needs, specifically pastureland needs especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The article points to the use of regionalised healthy diet recommendations as opposed to more plant-forward diet recommendations frequently used in other studies, as a potential driver of this finding. They claim this is potentially due to the relatively higher consumption rates of animal products in the regionalised recommendations.

The authors also note that other studies have previously found no forest decrease required to meet healthy diets, or even forest gain; findings that relied on the assumption of high yield increases, substantial dietary change and reductions in food waste and loss. They also relied heavily on assumptions of better feed: output ratios in mixed and pastureland systems. This paper, by contrast, considers the impact of crop yields that would evolve regionally under the combined influence of technological developments and climate change, noting that in sub-Saharan Africa the most common pasture practice is natural grazing, so efficiencies through technology are unlikely to have a significant impact.

To achieve healthy diets by 2050 without significant farmland and pasture land expansion, the authors conclude that the options include a mix of the following: sustainably increasing crop yields and cropping intensities, targeting plant-forward healthy diets specifically oriented to regional contexts, adjusting livestock rations to increase the proportion of concentrated feeds and quality forages, increasing imports from third countries, and reducing food waste and losses. In particular, more pasture land is needed, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In a wider group of regions, producing sufficient food without increasing agricultural land use only appears possible if we assume an optimistic scenario for increasing yields

Abstract

This paper analyses to what extent it would be possible to ensure food availability to the world population by 2050 with two objectives: healthy diets and no farmland expansion. Assumptions were made to project exogenous demand and supply variables. Climate change impacts on crop yields, grazing use intensities and maximum cultivable areas were taken into account. Cropland and pastureland needs were then estimated for 21 regions using a global biomass balance model. Simulation results established for two sets of crop yield projections (‘moderate’ versus ‘high’ growth) show that several regions (India, Rest of Asia, Near- and Middle-East countries and North Africa, as well as West Africa in the case of ‘moderate’ yield growth) would be constrained by their maximum cultivable areas with no deforestation. Our scenarios would be technically infeasible because of additional pastureland needs notably in sub-Saharan Africa. As a consequence, we analyse to what extent additional levers could reduce pastureland needs in sub-Saharan Africa.

Reference

Forslund, A., Tibi, A., Schmitt, B., Marajo-Petitzon, E., Debaeke, P., Durand, J.-L., Faverdin, P., Guyomard, H., 2023. Can healthy diets be achieved worldwide in 2050 without farmland expansion? Global Food Security 39, 100711.

Read the full article here and see our explainer on What is the land sparing-sharing continuum? and our report Grazed and Confused

Post a new comment »