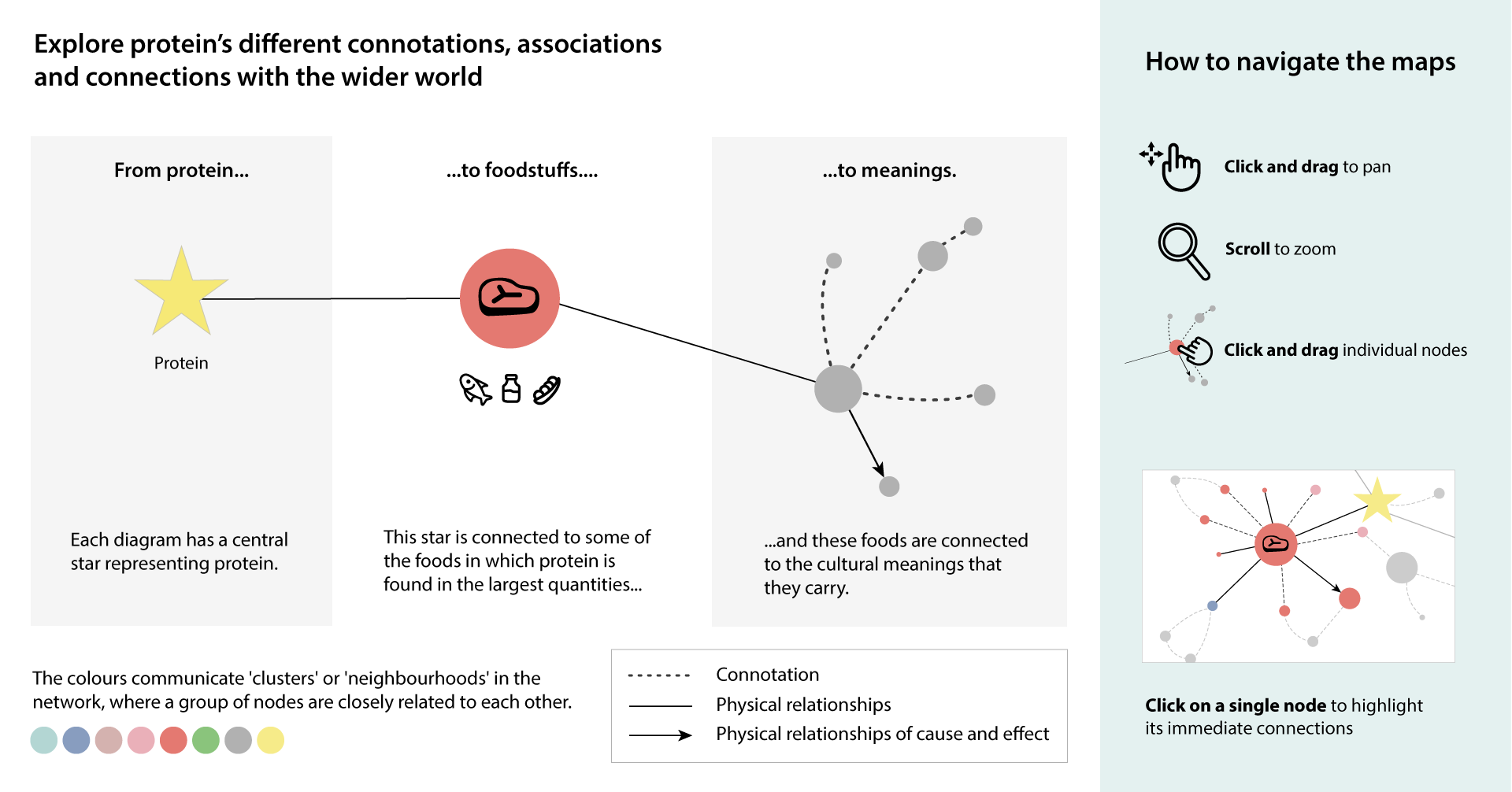

Protein meaning map for the UK

Protein—most venerated and least problematised of the macronutrients. We are advised to eat more of it to lose weight, to keep our health as we age, to build muscle, to have more energy; we are advised to feed our children more of it to help them grow taller, our pets more of it in the hope of healthy, glossy coats. Over its history protein has collected a wealth of different positive meanings from the foods it is connected with, some more based in science than others.

The foodstuff most strongly associated with protein is meat—so much so that many people think of meat as the singular source of dietary protein. This reflects the cuisine of the period when protein entered the public imagination: although ‘protein’ and related terms began to circulate in the scientific literature as early as the 1830s, it was not until the early 1900s that it began to be used in popular discourse. The habit of thinking about food in terms of nutrients (what Gyorgy Scrinis and Michael Pollan have referred to as ‘nutritionism’) spread slowly across the whole of the first half of the twentieth century, so it is in the food of 1900-1950 that we should look for the first and deepest connotations of protein. This was the era of ‘meat and two veg’ in British food. Meat had always played a major role in British diet, bearing symbolic significance as a social signifier (the food of the wealthy), a signifier of important moments (the food of feasts and celebrations) and the fuel of men and masculinity. Meat was typically the centrepiece of meal design, with bread or potatoes, sauces and vegetables to complement it. When protein is first talked about in popular sources like advertising, it is immediately connected with meat, whether as the scientific explanation for the healthfulness of meat, or as a comparator (‘this food has so much protein in that it can substitute for meat’). Thus it is unsurprising that protein’s most intimate association in the British imaginary remains that with meat, and from this protein inherits many meaty meanings: masculinity, strength, wealth and success, richness and heartiness.

The other main source of associations for protein in UK food culture is dairy. The earliest protein powders and protein-fortified foods sold in the UK (around 1900-1910) were based on milk protein, and milk has remained an important symbolic source of protein—particularly for children. This connects protein with ideas of femaleness and femininity, motherhood and care, childhood, infancy and growth. A similar complex of ideas connects protein with eggs and so with blandness, convalescence and nurture.

These connections between protein and animal source foods give rise to indirect links between protein and imagined stories of livestock farming. Protein becomes something sourced from a rural Arcadia, a natural landscape managed through proud farming tradition in which contented animals roam. This is perhaps the first image of food production offered to children in the form of nursery rhymes about and images of farm animals, and it hovers nebulously in much of our national thinking about meat and dairy.

Other major dietary sources of protein, like pulses, nuts and fish, feature far less saliently in the conceptualisation of what ‘protein’ is in UK culture. Others still, like bread and other grain-based foods, are so little associated with protein that most people in the UK would be surprised to learn that they contain any at all. In recent years, however, the nearly universally positive array of meanings connected with protein has begun to be troubled by more worrying associations: the negative environmental impacts of animal source foods; the negative health outcomes of eating meat; the cruelty and squalor associated with intensive livestock farming. Thus protein, like much of food production, is becoming a site of contested, conflicting meanings—and it is into this space that the hopeful entrepreneurs of the ‘alternative proteins’ movement come, offering a panacea in the form of all protein’s positives cut free from its growing negatives. What impact this will have on the public imagination in coming decades we can only wait and see.

About the authors

Tara Garnett is the director of TABLE and based in London. Tamsin Blaxter is a researcher for TABLE and based in Oxford. For more information about them, see the About us page.

Post a new comment »