Protein meaning map for Italy

We know that with globalisation, national and local systems, perspectives and tastes have given room to more general trends, very often initiated by more powerful countries and exported almost everywhere on the planet. However, we also know that some local elements, values or beliefs, even coming from the periphery of the Empire, may enter the global circuit at a certain point in the globalising process and spread as fast and wide as the dominant trends. Local and global play out this way even in the perception of protein.

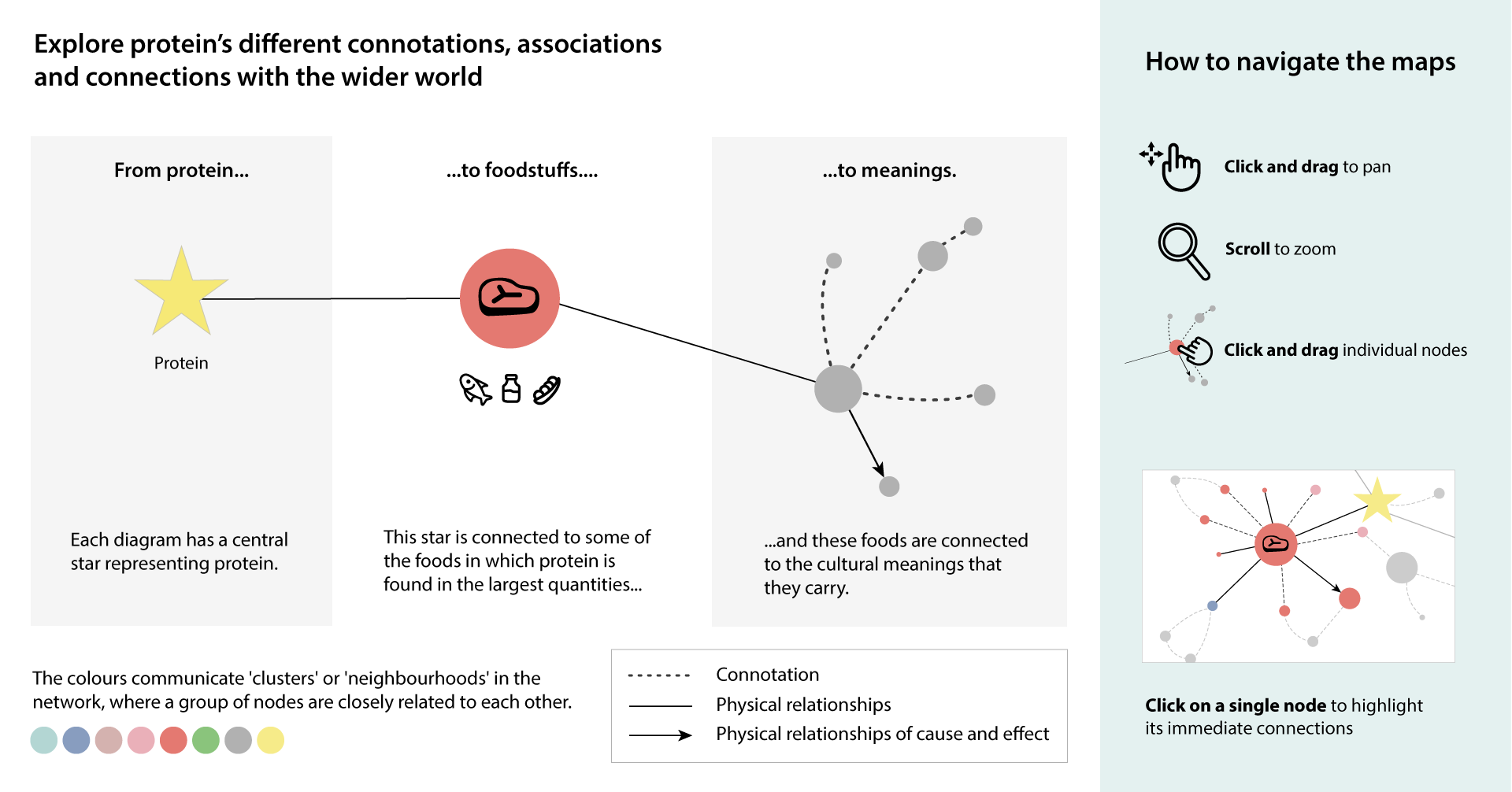

The map published here demonstrates that in the Italian approach to protein, some global values have now become a coherent part of the Italian mindset. The links between massive meat production and ecological damage or global warming, for example, have not been generated in Italy, but are today in the Italian collective imaginary. The masculine nature of eating meat was not, at the beginning, part of Italian meat culture, which considered meat a source of energy good for everyone, regardless of their gender. Even Fascism, really concerned with masculinity, never stressed meat consumption in its propaganda, focusing on other foods, such as rice. Today, conversely, these trends are part of Italian food culture, even though they have foreign origins.

Next to them in the diagram on Italy published here, however, there are Italian specificities. The whiteness of cheese, its continuous reference to the woman, even in disturbing sexist advertisements, may be an interesting case study. While meat has become, through global influences, something for men, mozzarella, for example, has come to be seen as a female form of protein, with its immaculate colour, drops of milk and rounded shape.

What is more, pulses, a staple abundantly produced in Italy even in refined, locally protected versions, are seen as a natural alternative to meat. The Italians have always had them in their fields, but only in recent decades have lentils or chickpeas acquired this social status and almost heroic role of purifying our tables from the impurity of meat, a role in society that Bourdieu would have loved and studied in depth.

In countryside and in a diet (the Mediterranean one) full of fruit and vegetables (and pulses), vegetarianism is thus not an anguished renunciation, apart from for a few irreducible carnivores in Tuscany and other few regions. Abstaining from meat is, instead, a concrete and tangible source of hope. Or better yet, a diet that many Italians have followed before, not knowing that it might one day be seen as a courageous moral choice.

In the end, this diagram, like every attempt to take a photograph of a social process, is a frozen image of a state of flux and, as such, a disputable tool. Tomorrow, it will be different from today. To see where all of this will lead us in the perception of protein, what we can do is to take a look at these last elements, which are specifically Italian. Some of them might become, tomorrow, global heritage of Italian origins, with the same destiny as pizza or spaghetti, today global foods of Italian origins flourishing on the streets of a great part of the planet.

About the author

Francesco Buscemi pursued a PhD on food and media at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. He teaches media studies at the Catholic University of Milan and taught at the universities of Stirling and Bournemouth. He also won the Santander Research Grant Fund for research on Nazi propaganda and meat. Francesco researches the relationships between media and food and the ever-changing meaning of the idea of eating an animal throughout the years and in future perspectives. He has focused on this issue in the book From Body Fuel to Universal Poison: Cultural History of Meat, 1900-the Present (Springer).

Post a new comment »