Table of contents:

- Introduction

- Section 1: The primary substance

- Section 2: Meat makes meat: the first protein fashion

- Section 3: Testing the lower limit: the end of the first protein fashion

- Section 4: 1918-1955: milk, aid and biopolitics

- Section 5: Protein fiasco

- Section 6: Epilogue

Suggested citation:

Blaxter, T., & Garnett, T. (2022). Primed for power: a short cultural history of protein. TABLE, University of Oxford, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Wageningen University and Research. https://doi.org/10.56661/ba271ef5

4. 1918-1955: milk, aid and biopolitics

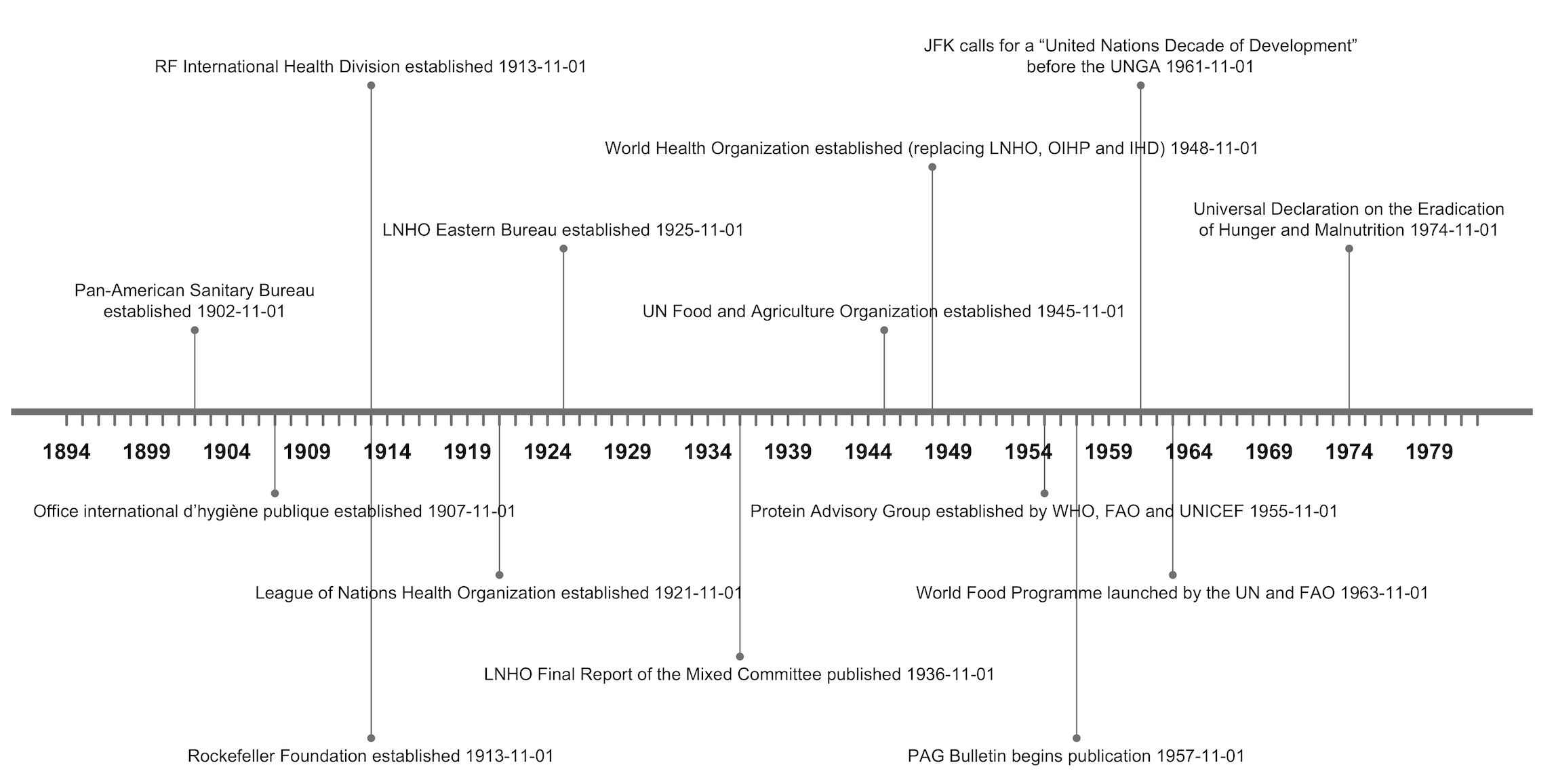

The 1900s and early 1910s had seen the foundation of many of the first international aid organisations and NGOs (see Figure 5); in the aftermath of the First World War, and with the establishment of the League of Nations Health Organization, these organizations came into greater prominence. They were initially focused on delivering food to war-torn Europe but, as Europe became more prosperous, ‘world hunger’ shifted to be seenas a characteristically African and Asian problem.124 The realisation that malnutrition was a particular issue in the colonies created a political incentive for colonial powers to find a diagnosis that was not poverty or a simple lack of food: whereas impoverishment would seem to imply colonial maladministration, if the explanation was something specific to the cultures of colonised populations then colonial governance could not be to blame.125 From the late 1920s onwards, this led to the renewal of the belief that many African and East Asian cultures suffered from a mistaken under-valuing of meat and dairy. Compounded by reports of the ignorance of mothers about infant nutrition, low intake of animal-sourced foods supposedly resulted in widespread protein deficiency.126

Figure 5: Timeline of important events in the history of international co-operation around nutrition and aid of relevance to the history of protein

An important part of this story was a study by J. L. Gilks, Director of Medical Services in Kenya, and John Boyd Orr, Director of the Rowett Research Institute in Aberdeen. This work, first published in the Lancet in 1927 and as a longer report in 1931, compared the diets of the Maasai and Kikuyu peoples in Kenya. The Kikuyu suffered from persistent public health problems (in particular widespread tropical ulcer, a bacterial disease associated with poverty in tropical climates127) and had lower average height, weight and strength than the Maasai — this undermined their utility as a labour force.128 Gilks & Orr characterised the Kikuyu as living “almost exclusively on a cereal diet”,129 eating meat only for ceremonial reasons (“indicating possibly a physiological craving”130), in contrast to the Maasai who lived “almost entirely on meat, milk and blood [...,] [an] exclusively protein diet”.131 They concluded that the difference in public health outcomes was due to the Kikuyu’s ‘vegetarian’ diet. In retrospect, it is clear that these were not accurate characterisations of the diets; in addition, Gilks & Orr wrongly assumed that they were observing longstanding food practices unchanged by colonisation.132 Nevertheless, over the 1930s, these findings were progressively projected and expanded to create an image of generalised cultural vegetarianism and consequent malnutrition among African agriculturalists.133 This contradicted the stereotype of the hunting, meat-eating ‘noble savage’ — an image intertwined with thinking about human evolution and attached in particular to the Maasai.134,135 Apparently, however, the cultural imagination was able to tolerate any resulting cognitive dissonance.

The explanation of hunger as resulting from nutritional ignorance echoed domestic politics in wealthy countries. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, nutritional investigations and explanations put particular focus on newly- discovered vitamins and minerals. Often referred to as “protective foods”, these were the nutrients du jour in the way that protein had been in the late 19th century, and it was feared that they were particularly lacking in modern, processed diets.136 However, this advancing nutritional science also led to great optimism that problems of malnutrition could be fixed by changing practices rather than expending more resources: if a nutritionist could construct a hypothetical healthy diet containing all the necessary nutrients on a given budget, then money could not be the cause of dietary ill-health among the poor.137 But in the international development sphere, this was just one of two competing views: the other, “progressive view” was to ascribe hunger to poverty, setting the blame firmly on colonial governments. The goal was a joined-up approach incorporating public health, nutrition, sanitation, education and the environment, and led by health professionals from Eastern Europe, South-East Asia and Latin America.138 In 1933, the League of Nations Health Organization challenged member states to tackle the problem of colonial nutrition head on, stating that “there is more honour to be gained in attempting to improve the situation than in concealing it”,139 but the Health Organization’s Mixed Committee, tasked with assessing the debate, tried to walk a line between the two approaches in its report The Problem of Nutrition, published in 1936.140 This report would be highly influential for many years to come.

Gilks & Orr’s study also engaged with high infant mortality rates. Again, they assigned these to dietary factors, first implying that they might be due to early weaning, but then concluding that this practice was itself a consequence of poor maternal nutrition.141 This was part of a wider trend: the profile of maternal, infant and child nutrition in research rose throughout the 1920s and 30s, and with these the perceived dietary importance of cow’s milk.

British governmentally-backed nutritional science during the First World War had concluded that “no diet for [infants and young children] can be considered satisfactory which does not contain a considerable proportion of milk”;142 since dairy production had been placed under state control, this put considerable pressure on governments to improve availability and prices. Influenced by reports of the cheaper, higher quality milk available to American consumers, pressure groups like the Women’s Cooperative Guild organised boycotts and marches over the period 1917-1920, calling for the government to take action to lower milk prices.143 During the 1920s, continued nutritional research—in particular, experimental studies which tested the effects of adding milk to the diet of institutionalised children—demonstrated that milk consumption promoted child growth, an idea that the dairy industry had already long been promoting in advertising.144,145 The equation of child growth with good health was well established in the thinking of nutritional science at this point, partly because labour and military demands for taller bodies had played such a significant role in the development of nutritional science.146 As a result, such findings represented unequivocal evidence for the necessity of milk. John Boyd Orr was also involved in this work, and was an enthusiastic milk advocate.147

The vehicle of motherhood and feminine care, milk carried a lot of symbolic potential. Given the focus on vitamins and protective foods, milk, a highly complex substance which could demonstrably serve as the sole source of nutrition for young mammals, seemed singularly promising; in the words of the Mixed Committee, it was “the nearest approach we possess to a perfect and complete food”.148 As already seen, because milk-drinking was not culturally universal it offered a useful rationalisation of imperial power and colonial ill-health. It fitted into a view of the world in terms of racial hierarchy in which white people were physically superior either due to or evidenced by their drinking milk.149 Nor was the use of milk as a nationalist symbol unique to colonising countries: in India, the cow became a metaphor for the colonised state and milk-drinking a symbolic antidote for lost strength; thus here too a lack dairy consumption came to connote national weakness.150

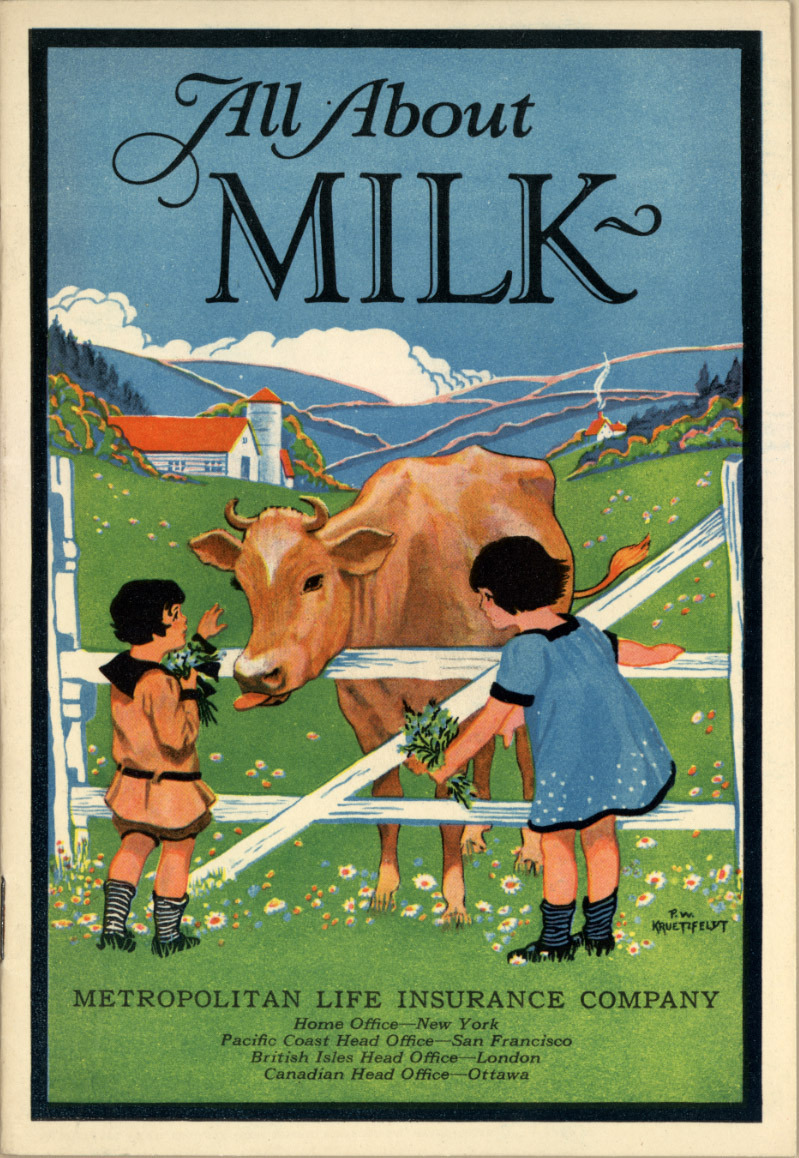

Advertising played a major role in popularising positive links between milk, growth and strength. The idea that milk was a uniquely complete food had been utilised in adverts at least since the first milk-derived protein supplements at the turn of the century.151 Lobbying and marketing bodies representing the dairy industry were set up in various countries, in many cases by the state. These included the US (the National Dairy Council, 1915), Sweden (the Milk Propaganda [Mjölkpropagandan], 1923, and later Swedish National Association of Dairies [Svenska Mejeriernas Riksförening], 1932), and Britain (the National Milk Publicity Council, 1920, and later the Milk Marketing Board, 1933), as well as Germany (1927), Finland (1927), Norway (1928), Japan (1931), Denmark (1932), Belgium (1938) and the Netherlands (1930s).152 Some were highly influential, and repeated both the claims of nutritionists and racialised imagery and language in their advertising.153,154 They also presented milk consumption in terms of a battle between unhealthy, artificial modernity and healthy nature.155 The line between the commercial activities of these groups and the public good was often blurred, with government-funded school milk programmes in Britain, Norway and the Netherlands partially motivated by the desire to find a profitable use for surplus milk production.156

Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. 1929 (Emergence of Advertising in America: 1850-1920, Duke University Libraries: CK0064)

The League of Nations’ The Problem of Nutrition included the first League-backed estimates of dietary requirements. It prescribed 1 gram per kilogram of bodyweight per day for adults. This was in line with the scientific consensus since the end of the First World War, but unlike most previous official recommendations the report also gave a value for infants: 3.5 grams per kilogram of bodyweight per day.157 Here, too, great emphasis was put on the importance of milk, especially for infant nutrition (“its value is unique and we cannot do without it”) in terms which repeated the racist-colonial frame (milk characterised “the dietary of civilised peoples”).158

The Second World War saw a repeat of the technocratic experiments of the First World War, with many European governments effectively nationalising food production and distribution through agricultural and horticultural programmes and rationing. These emergency measures lent prominence to nutritionists such as John Boyd Orr in Britain and led to a further reinforcement of the nutritional science of the time. As in Denmark in the First World War, countries like the Netherlands were able to partially mitigate threats to food security by rebalancing domestic food systems away from animal agriculture and towards cereals and potatoes.159 In Britain, by contrast, much emphasis was put on the importance of milk — and successes in public health were confidently (although, in retrospect, erroneously) ascribed to this strategy.160

Milk was now intimately associated with the creation of big, strong bodies for war (in an address in 1943, Winston Churchill commented that “There is no finer investment for a community than putting milk into babies”161)—and the creation of big, strong bodies continued to sit centre stage in the methods of nutritional science. As early as 1920, researchers had been aware of problems with one of the central tools of nutritional science, the study of the growth of young animals when fed different diets. Young animal growth was a singular, easily measurable metric — but one that would be especially sensitive to the nutrients required for tissue production and might be insensitive to those needed for other bodily functions. Assuming growth was an indicator of the total relationship between health and diet might thus be expected to overemphasise protein requirements and special requirements for particular amino acids.162 This lesson had not been learnt. In a telling example, post-war research

by British nutritionists McCance & Widdowson (both of whom had been deeply involved in the government’s wartime effort) demonstrated that child growth was insensitive to the choice of brown or white bread.163 This was taken to imply that, contrary to general belief, brown and white bread were nutritionally identical, prompting the British government to acquiesce to demands from the baking and milling industries for the freedom to produce white bread instead of brown.164,165

Figure 6: Svenska Mejeriernas Riksförening advert for dairy products, 1937.

The seeming success of wartime technocratic approaches to nutrition and rationing in the Allied countries helped to push back against the idea that world hunger and particularly colonial malnutrition were problems of poverty. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the contestation between technocratic and social approaches continued in the new United Nations institutions. US actors in particular tended to push for vertical, technocratic solutions to famine relief and other public health problems, which allowed them to make use of military expertise developed during the war.166 In many ways, patterns seen after the First World War repeated: initially the problem of hunger was global and remedial efforts were focused on Europe; when the European situation was stabilised the focus shifted to Africa, Asia and South America, and with this shift, the politics changed.167

The scene was now set for protein to return to the fore.

Footnotes

-

Erica Marie Nelson, Nicholas Nisbett, and Stuart Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition: Critical Reflections on Contested Pasts and Reimagined Futures’, BMJ Global Health 6, no. 11 (November 2021): e006337, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006337.

-

Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 567.

-

Michael Worboys, ‘The Discovery of Colonial Malnutrition between the Wars’, in Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies, ed. David Arnold (Manchester University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526123664.00013; Cynthia Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science: The Orr and Gilks Study in Late 1920s Kenya Revisited’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies 30, no. 1 (1997): 49, https://doi.org/10.2307/221546; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 22.

-

D. C. Robinson et al., ‘The Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Tropical Ulcer (Tropical Phagedenic Ulcer)’, International Journal of Dermatology 27, no. 1 (January 1988): 49–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb02339.x; Stefano Veraldi et al., ‘Tropical Ulcers: The First Imported Cases and Review of the Literature’, European Journal of Dermatology 31, no. 1 (February 2021): 75–80, https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2021.3968.

-

The Maasai, though healthier and larger, were “negligible” “[a]s a labour force” because “[t]heir interest is in cattle and nothing else, and apart from engaging as herdsmen they do not enlist for work.”

-

J. L. Gilks and John Boyd Orr, ‘The Nutritional Condition of the East African Native’, The Lancet, 12 March 1927, 561.

-

Gilks and Orr, 561.

-

Gilks and Orr, 561.

-

Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science’; Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 559.

-

Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science’, 52.

-

Dorothy L. Hodgson, ‘“Once Intrepid Warriors”: Modernity and the Production of Maasai Masculinities’, in Gendered Modernities, ed. Dorothy L. Hodgson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2001), 105–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-09944-0_5; Lotte Hughes, ‘“Beautiful Beasts” and Brave Warriors: The Longevity of a Maasai Stereotype’, in Ethnic Identity: Problems and Prospects for the Twenty-First Century, ed. Lola Romanucci-Ross, George A. De Vos, and Takeyuki Tsuda, 4th ed (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006), 264–94.

-

Even before the famous ‘Man the Hunter’ symposium in 1966, generations of anthropologists have discussed the role of hunting and meat-eating in human evolution—in short, to what extent ‘[H]uman hunting underlies humanness.’ It is beyond the scope of this essay to go into these debates in any detail. Suffice it to say that the image of a (crucially) male human hunter is a recurring motif in both academic and popular thinking about pre-modern humans and in turn tends to shape conceptions of modern hunter-gatherers. It also undoubtedly plays a role in the primitivist strain of modern dieting culture that finds its expression in the Paleo Diet, the Carnivore Diet, and so on. Travis Rayne Pickering, Rough and Tumble: Aggression, Hunting, and Human Evolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 8; Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore, eds., Man the Hunter: The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development : Man’s Once Universal Hunting Way of Life (London: Taylor and Francis, 1968); Craig B. Stanford and Henry Thomas Bunn, Meat-Eating & Human Evolution (Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press, 2001); Christine Knight, ‘Indigenous Nutrition Research and the Low-Carbohydrate Diet Movement: Explaining Obesity and Diabetes in Protein Power’, Continuum 26, no. 2 (April 2012): 289–301, https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2011.562971; Dorsa Amir, ‘A Viral Twitter Thread Reawakens the Dark History of Anthropology’, Nautilus, 21 April 2022, https://nautil.us/a-viral-twitter-thread-reawakens-the-dark-history-of-….

-

136 Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:15; Jia-Chen Fu, ‘Confronting the Cow’, in Moral Foods: The Construction of Nutrition and Health in Modern Asia, ed. Qizi Liang and Melissa L. Caldwell, Food in Asia and the Pacific (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2019), 50.

-

J. P. W. Rivers, ‘The Profession of Nutrition—an Historical Perspective’, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 38, no. 2 (September 1979): 228, https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19790035.

-

Tom Scott-Smith, On an Empty Stomach: Two Hundred Years of Hunger Relief (Cornell University Press, 2020), 75–89, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501748677; Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’, 3.

-

E. Burnet and W. R. Aykroyd, ‘Nutrition and Public Health’, League of Nations: Quarterly Bulletin of the Health Organisation, no. 4 (1935): 452; cited in Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 560.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936; Technical Commission of the Health Committee, The Problem of Nutrition, vol. II: Report on the Physiological Bases of Nutrition (Geneva: League of Nations Publications Department, 1936); Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, vol. III: Nutrition in Various Countries (Geneva: League of Nations Publications Department, 1936); Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’.

-

Gilks and Orr, ‘The Nutritional Condition of the East African Native’, 561.

-

Food (War) Committee, Report of the Food (War) Committee of the Royal Society on the Food Requirements of Man and Their Variations According to Age, Sex, Size, and Occupation, 18 (emphasis original).

-

Deborah Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011), 253–57.

-

Peter J. Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’, The Economic History Review 58, no. 1 (2005): 61–62, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00298.x; Jon Pollock, ‘Two Controlled Trials of Supplementary Feeding of British School Children in the 1920s’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99, no. 6 (June 2006): 323–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680609900624; Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History, 260–62; Andrea S. Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, The Routledge Series for Creative Teaching and Learning in Anthropology (New York: Routledge, 2011), 60,77-78.

-

Whether milk consumption has a particular effect on child growth beyond infancy is a complex issue. A century after these initial claims we can say that there is weak evidence for a small effect on lean body mass but not on height, but the question is far from settled. Nevertheless, a general belief that increasing milk consumption is a good way to promote child growth (and final adult height) is probably more widespread around the world today than it was in the twentieth century, since Western cultural beliefs about food have spread along with Western eating patterns in recent decades. Clear examples of this are found in government policies to increase milk consumption by children in order to promote growth in countries like China and Thailand which have little history of dairy consumption and where drinking milk has traditionally had very different (indeed, negative) connotations. On the related question of the effect of protein intake on infant growth, we can now say, contrary to assumptions through much of the 20th century, that there is none—at least within the range of protein contents in formulae and breastmilk. Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, 78- 84,96-102; D Joe Millward, ‘Interactions between Growth of Muscle and Stature: Mechanisms Involved and Their Nutritional Sensitivity to Dietary Protein: The Protein-Stat Revisited’, Nutrients 13, no. 3 (25 February 2021): 40–43, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030729.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; modern research is now complicating a neat equation of greater final height and better health, with, for example, higher incidence of some cancers among taller people. G. David Batty et al., ‘Height, Wealth, and Health: An Overview with New Data from Three Longitudinal Studies’, Economics & Human Biology 7, no. 2 (July 2009): 137–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2009.06.004.

-

Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’, 64.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:58.

-

One 1933 textbook on agriculture stated that “[a] casual look at the races of people seems to show that those using much milk are the strongest physically and mentally, and the most enduring of the people of the world”; U. P. Hedrick, A History of Agriculture in the State of New York (New York: New York Agricultural Society, 1933); cited in E. Melanie DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 115.

-

Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, 102–3.

-

For example, in an advert for Plasmon: ‘Nature has elaborated one food, and only one. All others are merely adaptations. This food is milk.’ The International Plasmon Ltd., ‘PLASMON’, Manchester Courier, 21 June 1901, sec. Advertisements, The British Newspaper Archive.

-

Carin Martiin, ‘Swedish Milk, a Swedish Duty: Dairy Marketing in the 1920s and 1930s’, Rural History 21, no. 2 (October 2010): 213–32,https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956793310000063.

-

DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink, 117–18.

-

In an interesting example which unites the themes of milk-marketing and race, adverts by the Swedish Milk Propaganda in the 1920s and 30s often contrasted the lively and strong ‘milk-boy [mjölkpojken]’ with the weak ‘coffee-boy [kaffepojken]’. A 1934 magazine article extolling milk-drinking was illustrated with children’s drawings inspired by listening to a radio programme on health. In one, the coffee-boy has been transformed into a black boy, and the caption reads: ‘You, nigger-boy, keep your coffee! And you, Swedish girl, drink good, white milk. [Du, negerpojke, behåll du ditt Kaffe! Och du, svenska flicka, drick du den goda, vita mjölken.]’ Jenny Damberg, Nu äter vi!: de moderna favoriträtternas okända historia, 1. pocketutg (Stockholm: Ponto Pocket, 2015).

-

An example from a 1937 Swedish advert is particularly striking: “The rush of the age grips us. It forces us into an artificial way of life that will make us forget that we are yet children of nature with roots in the earth, and not mere cogs in a machine. Now more than ever we must find the power to resist in the sources of nature.” [“Tidens jäkt griper omkring sig. Den tvingar oss in i en konstlad livföring, som kommer oss at glömma, att vi trots allt äro naturens barn med rötter i jorden och icke blott kuggar i ett maskineri. Nu mer än någonsin måste vi hämta motståndskraft ur naturens källor.”] Svenska Mejeriernas Riksförening, 1937, and cf. Figure 6.

-

Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’; A. Andresen and K. T. Elvbakken, ‘From Poor Law Society to the Welfare State: School Meals in Norway 1890s-1950s’, Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 61, no. 5 (1 May 2007): 374–77, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.048132.

-

Technical Commission of the Health Committee, The Problem of Nutrition, II: Report on the Physiological Bases of Nutrition:15.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:58.

-

M. J. L. Dols and D. J. A. M. van Arcken, ‘Food Supply and Nutrition in the Netherlands during and Immediately after World War II’, The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 24, no. 4 (October 1946): 319, https://doi.org/10.2307/3348196.

-

Rivers, ‘The Profession of Nutrition—an Historical Perspective’, 229–30; Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S484.

-

Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History, 254.

-

Sherman, Gillett, and Osterberg, ‘Protein Requirement of Maintenance in Man and the Nutritive Efficiency of Bread Protein’, 106–7.

-

Robert Alexander McCance and E. M. Widdowson, ‘Old Thoughts and New Work on Breads White and Brown’, The Lancet 269 (1955): 205–10.

-

White bread was financially more profitable for commercial bakeries for several reasons: it suited their machines; had a longer shelf-life; and it allowed them to sell the bran and wheatgerm separately for use in animal feed and as an input to the production of nutritional supplements.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S483.

-

Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’, 4.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 23.

Post a new comment »