Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa:

- Introduction

- Background

- Research Methodology

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s Agricultural Investment Landscape

- Investor Visions

- National Subsidies and Global Market

- Conclusions

- Glossary

Suggested citation:

Brice, J., (2022) Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa. TABLE Reports. TABLE, University of Oxford, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Wageningen University and Research. doi.org/10.56661/d8817170

Summary

- This report focuses exclusively on investment in protein production within sub-Saharan Africa itself. However, protein producers elsewhere in the world often receive far larger volumes of finance than their sub- Saharan African counterparts and investment outside the region shapes sub-Saharan Africa’s food system in important ways.

- Interviewees often highlighted the role of government subsidies to meat, milk and animal feed producers in other parts of the world in shaping global trade in meat and dairy products. For instance, in 2020 OECD Member States provided $50.1bn in Producer Single Commodity Transfers (SCTs) to meat and dairy producers. Meanwhile, Chinese meat and dairy producers received $45.2bn in producer SCTs during 2020. Both of these figures far exceed the $22.0bn of total investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s entire Agriculture, Forests and Fisheries sector recorded by FAOSTAT in 2019.

- Several interviewees suggested that these subsidies enabled animal products produced in Europe, North America and middle-income countries including Brazil and China to be imported into sub-Saharan African markets at prices below their cost of production. They claimed that local producers were in many cases unable to match the low prices at which imported products could be offered, effectively enabling producers elsewhere in the world to undercut and outcompete sub-Saharan African farmers and pastoralists.

- Certain interviewees argued that the availability of subsidised animal products was deterring private sector investment into livestock agriculture within the region. By their account, financial institutions such as commercial banks and private equity funds are reluctant to finance meat or dairy producers who face competition from imported animal products because they are concerned that such firms will be unable to produce a profit for their investors.

One important limitation of this report is that it focuses exclusively on investment in protein production within sub-Saharan Africa itself. Delimiting the scope of the report in this way was necessary in order to ensure that the research on which it is based it would both methodologically feasible and intellectually coherent. However, it is important to acknowledge both that protein producers in other parts of the world receive far larger volumes of investment than their sub-Saharan African counterparts (as discussed in Chapter 4) and that investment outside the region shapes sub-Saharan Africa’s food system in important ways.

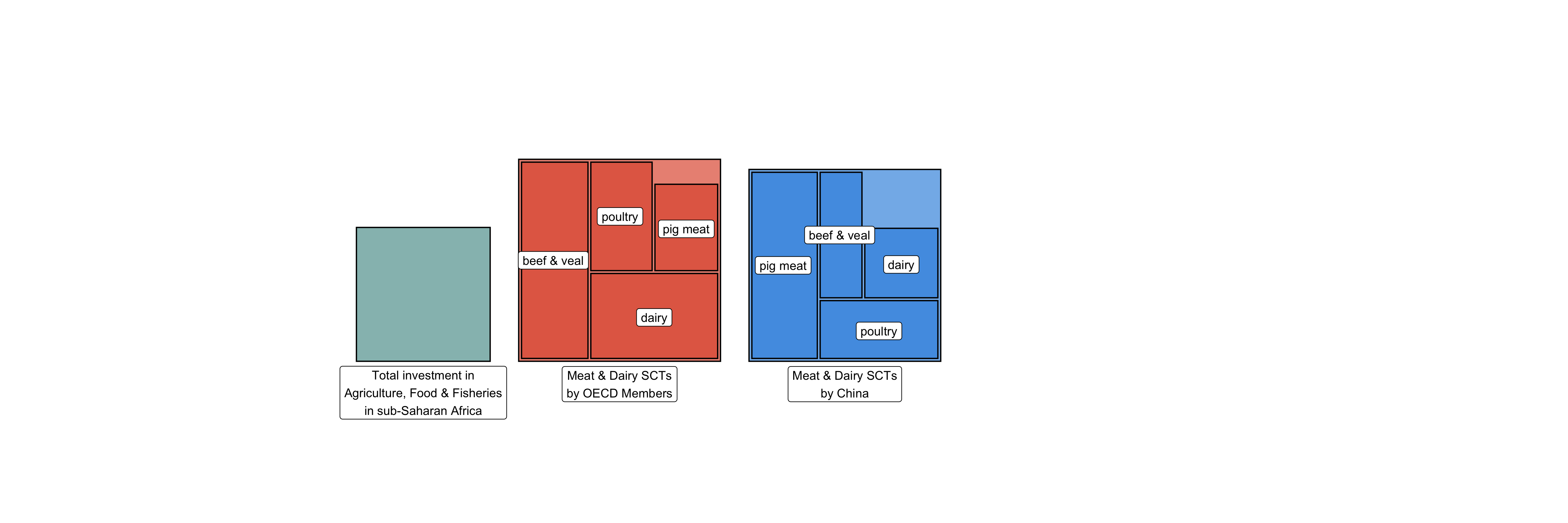

Interviewees were often particularly eager to draw attention to the role played by public sector investment in livestock agriculture – in the form of subsidies given to producers of meat, milk and animal feed by governments in both the Global North and certain middle-income countries – in shaping the production of (and global trade in) meat and dairy products. The magnitude of these financial flows can be illustrated through analysis of the OECD’s Producer Support Estimate (PSE) database. The PSE database records that in 2020 OECD Member States(5) provided their meat and dairy producers with $50.1bn in Producer Single Commodity Transfers (SCTs) – a measure of the annual monetary value of gross transfers from consumers and taxpayers to agricultural producers arising from policies linked to the production of a single commodity. This combined figure includes the provision by OECD countries of $17.2bn in SCTs to beef and veal producers, $14.3bn to dairy producers, $9.0bn to poultry producers and $7.5bn to producers of pig meat. Meanwhile China alone provided $45.2bn in producer SCTs during 2020 including $16.1bn for producers of pig meat, $9.2bn for poultry producers, $7.2bn for beef and veal producers and $7.0bn for dairy producers. Public sector investment in animal products in the form of producer SCTs provided both by the OECD Member States and by China thus dwarfs the $22.0bn of total investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s entire Agriculture, Forests and Fisheries sector recorded by FAOSTAT in 2019 (as illustrated in Fig. 15). Taken together, public sector investment by OECD Member States and China also accounted for the majority of the $112.1bn in SCTs which the OECD estimates was provided to meat, dairy and egg producers worldwide during 2020.

Several interviewees suggested that these producer SCTs had enabled meat and dairy products produced in Europe, North America and middle-income countries including Brazil and China to be made available on global (and sub-Saharan African) markets at prices below their real cost of production. Such products, they suggested, were imported in significant quantities into many sub-Saharan African countries, where they competed against animal products supplied by local farmers and pastoralists. They claimed that local producers were in many cases unable to match the low prices at which imported products could be offered, reiterating arguments that agricultural subsidies to farmers in the Global North (and the weakening of import controls in the Global South) have often “caused havoc for developing country farmers whose own production incentives were harmed by the availability of inexpensive imported food” (Clapp, 2012: 58). Such interviewees suggested that this public sector investment in animal protein production was thus effectively enabling producers elsewhere in the world to undercut and outcompete farmers and pastoralists in sub-Saharan Africa. This argument was made in the most general terms by one interviewee who worked for a DFI:

“Unfortunately livestock production in Africa is really handicapped by the fact that there is importation from Europe, United States, UK of accidental products – the milk powder, cheap poultry parts – which are really hampering the development of a commercial system in Africa. (...) Most of the products that are consumed can be produced in Africa but, you know, being on the world market at ridiculous prices, subsidised prices, they’re destroying the opportunity for some people to really get into the livestock production system in a commercial way.”

(Interview 10, Development Finance Institution)

Figure 15: Total investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s Agriculture in comparison to SCTs to provided to meat and dairy producers (OECD and China) during 2019. Data sources: OECD Producer Support Estimate database and FAOSTAT database.

The green box represents the $22bn of total investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector recorded by the FAO during 2019. Meanwhile the red and blue boxes represent the SCTs provided to meat, dairy and egg producers by OECD countries ($50.1bn) and by China (45.2bn) during the same year. Differences in size between the boxes indicate differences in the scale of investment provided.

Certain interviewees argued that the availability of subsidised animal products was ‘hampering the development’ of commercial meat and dairy production systems in sub-Saharan Africa in part through deterring private sector investment into livestock agriculture within the region. By their account financial institutions such as commercial banks and private equity funds are reluctant to finance meat or dairy producers who they know will face competition in their home markets from imported animal products because they are concerned that such firms will be unable to produce a profit for their investors. In these interviewees’ estimation, the existence of subsidised imported animal products thus played an important role in deterring investment which might otherwise enable sub-Saharan Africa’s animal protein producers to adopt new agricultural and processing methods – and develop more formal value chains – which might bring them closer to price parity with products produced overseas. It thus actively impeded the expansion and commercialisation of certain forms of livestock production in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Interviews with commercial investors provided some evidence of this effect (as discussed during Chapter 5’s analysis of the Protein for Profit vision). Notably, one interviewee employed by an international commercial bank illustrated this phenomenon using the example of the Ghanaian poultry market:

“Ghana has a relatively good business climate. But the problem with chicken is, it’s very open. So West Africa is always very exposed to imports for the chicken legs, you know, the cheaper cuts from Europe and Brazil and US, and that makes it a bit tricky I would say. (...) whereas there is not a lot of imports yet coming into East Africa, so that means local industry is protected.”

(Interview 14, commercial bank)

Such examples illustrate the importance of situating investment in protein production within sub-Saharan Africa within broader political economies of finance which may have far-reaching impacts on the development of food systems. While exploring these wider patterns of investment is beyond the scope of the current report, it is an important area of investigation for future research.

Footnotes

5 At present the OECD has 38 Member States including Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Poland, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, South Korea, Türkiye, the United Kingdom and the United States. Most (but not all) EU Member States are also members of the OECD.

References

-

Clapp J (2012) Food. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Post a new comment »