Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa:

- Introduction

- Background

- Research Methodology

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s Agricultural Investment Landscape

- Investor Visions

- National Subsidies and Global Market

- Conclusions

- Glossary

Suggested citation:

Brice, J., (2022) Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa. TABLE Reports. TABLE, University of Oxford, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Wageningen University and Research. doi.org/10.56661/d8817170

Summary

- This chapter analyses publicly available statistics on agricultural investment in sub-Saharan Africa in order to establish which groups of investors are most prominently involved in financing agricultural production – and, where possible, in financing protein production specifically – within the region.

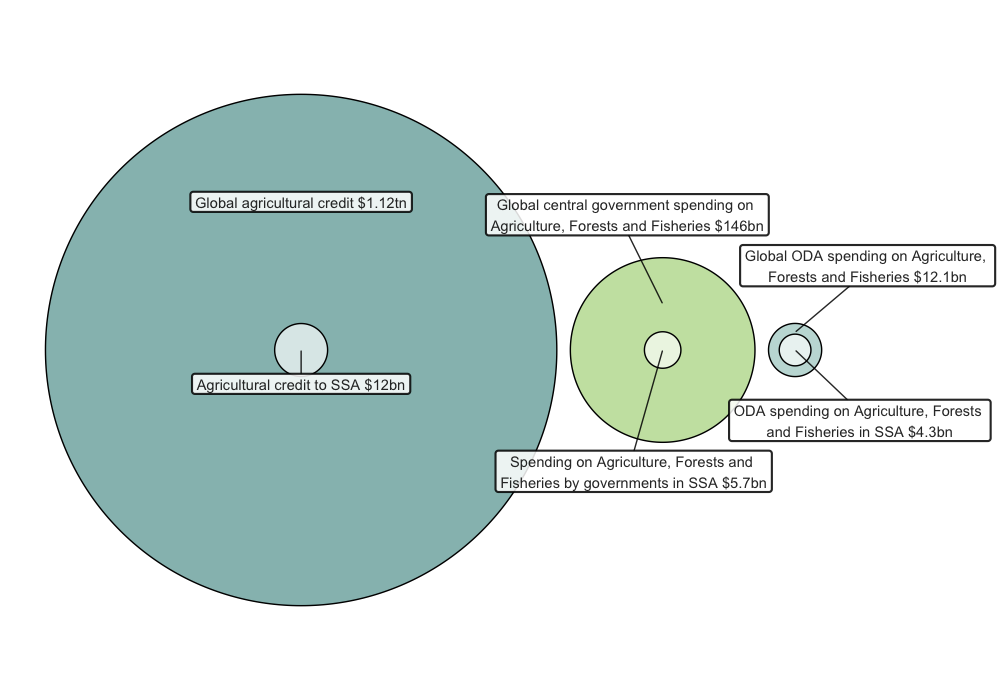

- Government spending and agricultural credit provided by the banking sector are the two largest sources of agricultural investment at the global scale. However, sub-Saharan Africa’s Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector receives relatively little investment from either of these sources. In 2019 sub- Saharan Africa accounted for only 4% of global government spending on the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector and a mere 1% of global agricultural credit.

- Sub-Saharan Africa receives 35% of global Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) spending on the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector. However, ODA accounts for only a small proportion of global agricultural investment.

- Private sector financial institutions appear to play a smaller role in sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural finance landscape than in those of most other regions. The main sources of private sector agricultural investment within the region are foreign direct investment by international agribusiness corporations, private equity funds and commercial banks.

- Little data relating specifically to investment in protein production in sub-Saharan Africa is publicly available, meaning that it is not possible to estimate reliably what proportion of total agricultural investment into the region is devoted to protein production. Data on government and private sector investment is particularly sparse.

- However, the proportion of total ODA spending on agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa allocated explicitly to the livestock and fisheries sectors has grown from 6.5% in 2011 to 14.8% in 2020. This suggests that ODA funders may have begun to place greater importance on the livestock and fisheries sectors in recent years.

This chapter analyses publicly available statistics on agricultural investment in sub-Saharan Africa in order to establish which groups of public, private and third sector investors are most prominently involved in financing agricultural production within the region. While its aim in doing so is to establish who finances protein production in sub-Saharan Africa, it is important to note that data relating specifically to investment in protein production within the region is scarce.

As a result, much of this chapter’s analysis is based on data which describes patterns of investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural sector in general, operating on the assumption that a certain proportion of this investment will be devoted specifically to protein production. It is also important to note that investment in protein production by individuals and families is not routinely captured in official statistics, and its relative importance therefore could not be estimated in this analysis. The first section of this chapter reviews broad patterns of agricultural investment in sub-Saharan Africa, while the second section provides a more detailed analysis both of the available data relating specifically to investment in protein production within the region and of this data’s limitations.

Agricultural Investment

Data held by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s FAOSTAT database shows that agricultural credit – in the forms of “loans and advances given by the banking sector to farmers or to rural households, to agricultural cooperatives or to any agri-related businesses” (FAO, 2022: 6) – represents the largest single source of investment in the global Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector. In 2019 the banking sector provided $1.12tn of agricultural credit worldwide, while global central government expenditure on the Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector totalled $146bn – meaning that at the global scale government spending also represents an important (if much smaller) source of agricultural investment.

However, sub-Saharan Africa’s Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector receives only a small proportion of these global flows of agricultural credit and central government spending. Despite holding 14% of the world’s population, 14% of the global livestock population and 15% of the world’s agricultural land, in 2019 the region accounted for only 4% ($5.7bn) of global central government investment in the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector and a mere 1% ($12bn) of global agricultural credit (as illustrated in Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Financial flows into sub-Saharan African Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries as a proportion of global agricultural investment, 2019. Data source: FAOSTAT database.

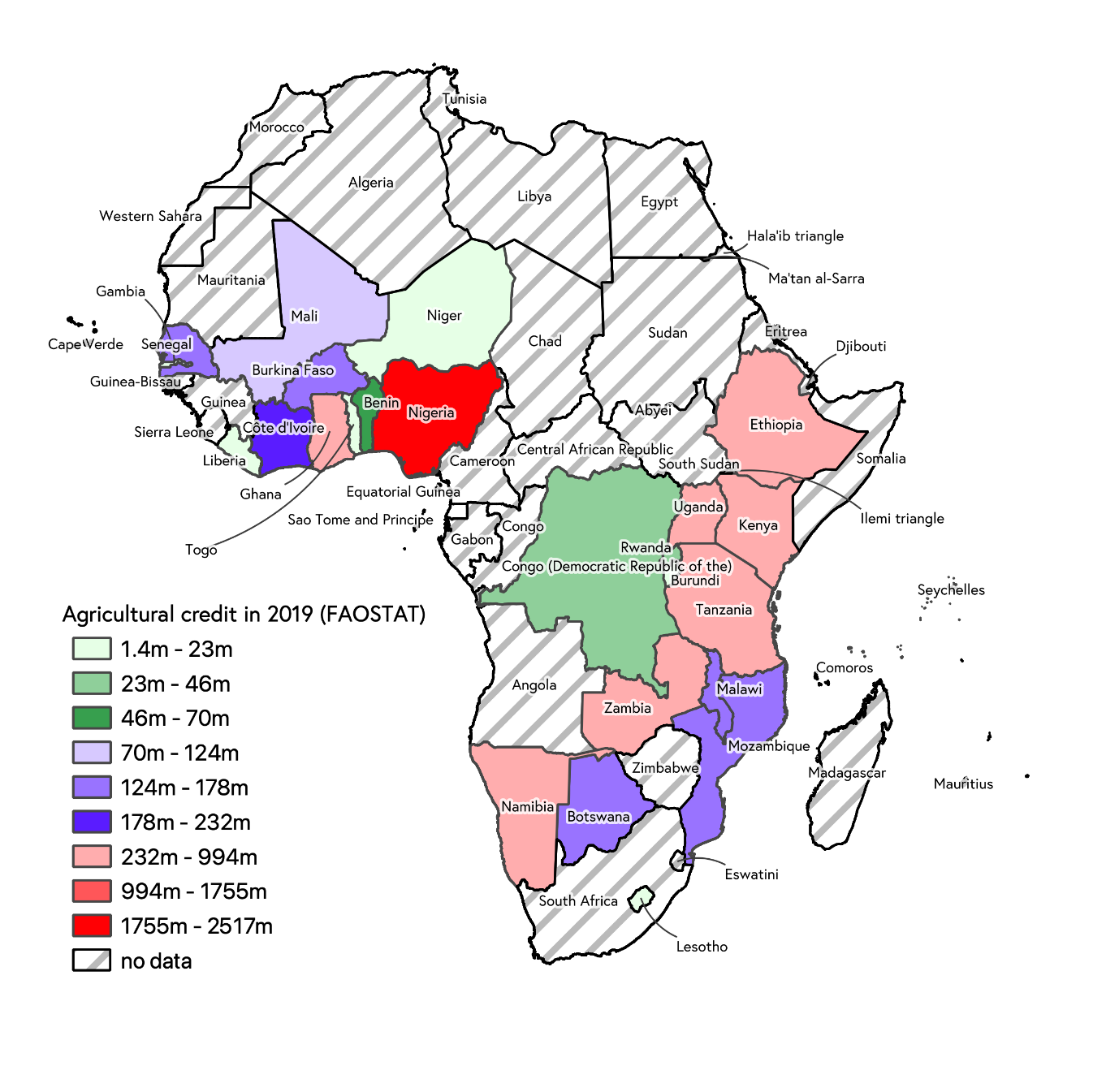

Figure 8: Agricultural credit investment across sub-Saharan Africa, 2019. Data source: FAOSTAT database.

As Fig. 8 illustrates, of the 26 sub-Saharan African countries which reported agricultural credit data to the FAO in 2019, Nigeria accounted for the largest volume of agricultural credit ($2.5bn) followed by Tanzania ($824mn), Kenya ($794mn), Ethiopia ($701mn) and Uganda ($583mn). By contrast, in 2019 Asia accounted for 49% of global agricultural credit ($550bn), with China alone receiving $194bn and India receiving a further $167bn. Meanwhile, Europe received 29% of global agricultural credit ($322bn) and the Americas received 12% ($134bn).

While most sub-Saharan African countries are marginal to global flows of agricultural credit, the region is the world’s largest recipient of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) spending on the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector. However, global ODA spending on this sector is relatively low – totalling only $12.1bn in 2019. As a result, although sub-Saharan Africa received 35% of global ODA spending on the Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing sector in 2019, this represents an investment of only $4.3bn – a relatively modest sum by global standards.

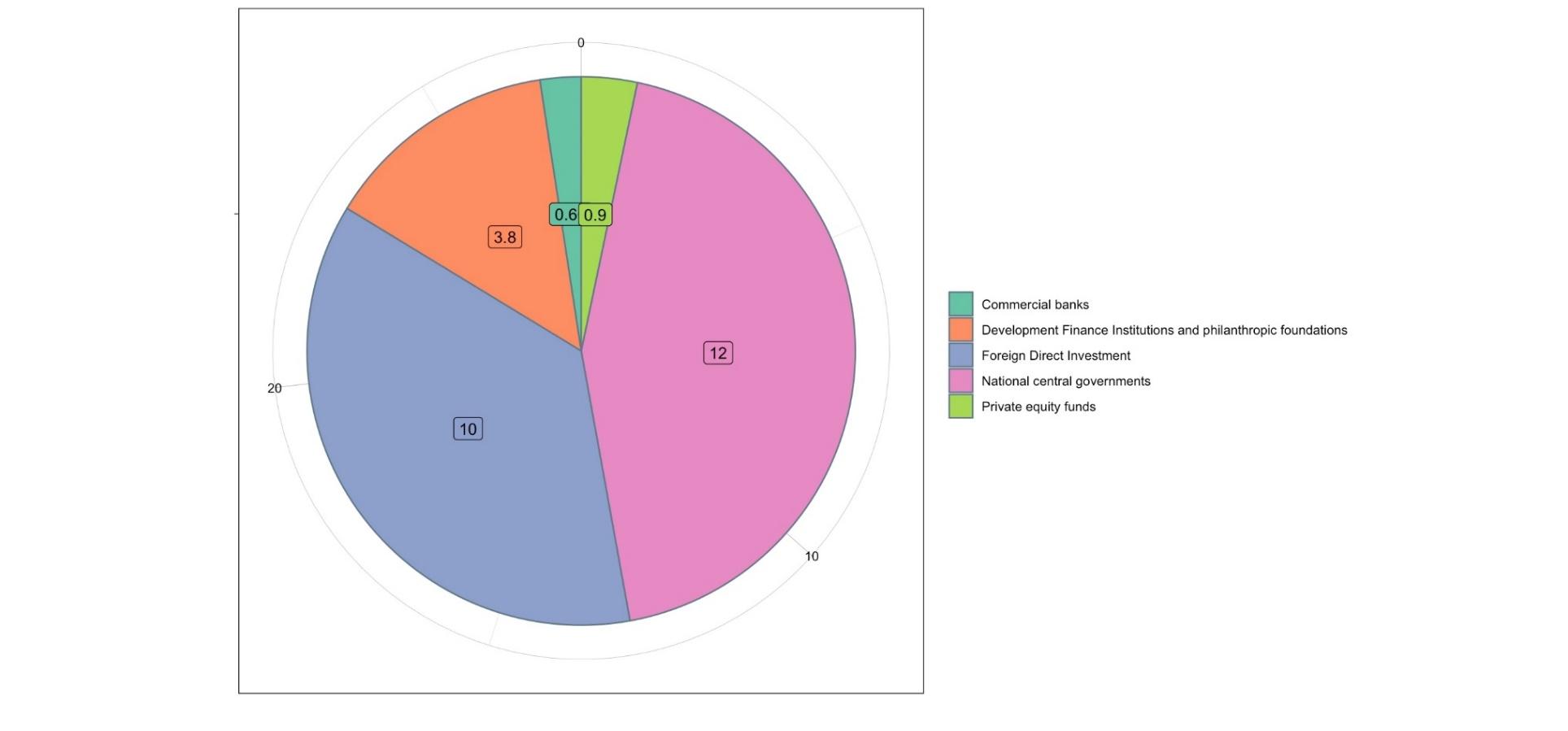

Research conducted separately by the African Development Bank (2016, 2021) provides a more detailed summary of the landscape of agricultural investment within Africa (including North Africa). While the African Development Bank’s analysis draws on different underlying datasets and classifies financial flows differently, making precise comparisons to the FAO’s data difficult, it estimates that total investment into African agriculture in 2014 was a relatively similar $27.36bn. It further estimates that $15.8bn (58%) of this funding was provided by public sector investors, while $11.56bn (42%) was invested by private sector organisations. According to the African Development Bank’s estimate (and as illustrated below in Fig. 9), as of 2014 the main public sector investors in agriculture across Africa were:

- National governments (whose combined agricultural expenditure totalled $12bn)

- Multilateral development finance institutions (DFIs), bilateral ODA spending and philanthropic organisations (whose combined total expenditure was $3.8bn)

Meanwhile, the major sources of private sector finance were:

- Foreign direct investment by international agribusiness corporations (estimated to have totalled $10bn)

- Private equity funds (estimated to have invested $900mn in African agricultural enterprises).

- Commercial banks (estimated to have loaned $660mn to the agricultural sector)

Figure 9: Investment in African agriculture by source, 2014. Data source: African Development Bank (2016).

In summary, analysis of data compiled by the FAO and the African Development Bank suggests that sub-Saharan Africa’s Agriculture, Food and Fisheries sector receives far less investment overall than do those of other regions. The volumes of agricultural credit provided to agricultural producers within the region appears especially small. This suggests that private sector financial institutions such as banks and private equity funds are likely to play a less prominent role in sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural finance landscape than in those of most other regions. Meanwhile ODA (and the Development Finance Institutions which provide it) appears to represent a more important source of agricultural investment in sub-Saharan Africa than it does elsewhere.

Protein Production

While conducting desktop research for this project, the author attempted to refine the African Development Bank’s analysis by examining which groups of investors might be providing the largest quantities of finance to protein production in sub-Saharan Africa. However, limitations in publicly available data sources made it difficult both to ascertain what proportion of agricultural investment is allocated specifically to protein production and (as a result) to establish whether the largest overall investors in African agriculture are also the main investors in protein production on the continent. Importantly, the data disclosed by national governments to publicly available sources does not typically disaggregate agricultural expenditure to provide information on the quantity of funding provided to specific agricultural subsectors such as livestock agriculture, aquaculture and legume production.

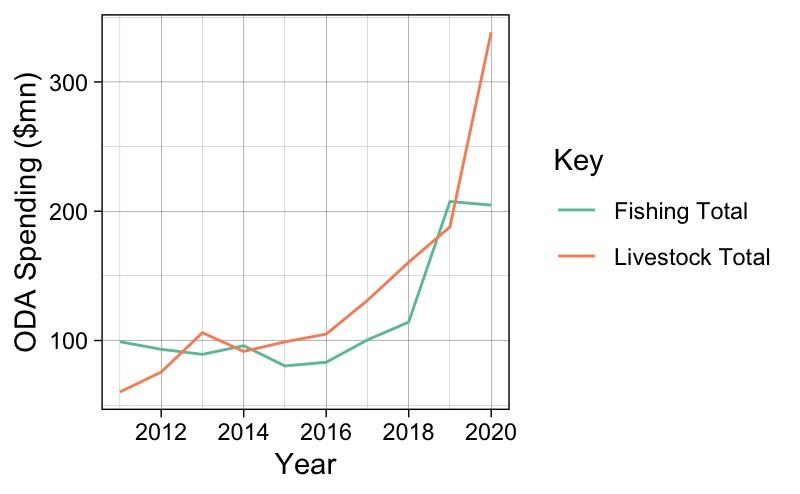

However, the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System (CRS) provides a more detailed breakdown of the sub-sectoral focus of ODA funding allocated towards agricultural development. Analysis of the CRS database revealed that in 2020 sub-Saharan African countries received $3.66bn of agricultural development funding, $338.5m of which was targeted at the livestock agriculture sector (including veterinary services). Meanwhile, $204.7m of agricultural development funding was targeted towards the fisheries sector. As such, in 2020 approximately 9.2% of total ODA spending on agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa was allocated explicitly to the livestock sector, while 5.6% was allocated directly to fisheries.

Although funding allocated explicitly to animal protein production thus makes up a relatively small proportion of total ODA spending on agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa, it is important to note that total spending on fisheries has doubled – and spending on the livestock sector has increased more than five-fold – since 2011 (as illustrated in Fig. 10). By contrast, total ODA spending on agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa grew by roughly 50% over the same time period. As such, the percentage of agricultural development funding for sub-Saharan Africa which is allocated directly to the livestock and fisheries sectors increased from 6.5% in 2011 to 10.5% in 2019, and reached 14.8% in 2020. This suggests that ODA funders may have begun to place greater importance on the livestock and fisheries sectors in recent years.

While the OECD data provides the most detailed publicly available breakdown of the focus of public sector agricultural investment in sub-Saharan Africa, it has its own limitations. As some interviewees who contributed to this project pointed out, funding which is provided by philanthropic organisations, DFIs or national governments to enterprises or communities involved in protein production may be allocated to projects whose primary objectives lie in fields such as regional economic development or gender equality. As a result, such funding may not be recorded as investment in protein production, even if it is used to support activities such as the provision of training in aquaculture techniques to smallholder farmers or the establishment of a micro-finance scheme for women engaged in small-scale poultry farming.

Figure 10: Overseas Development Assistance spending on animal protein production in sub-Saharan Africa, 2011-2020. Data source: OECD Creditor Reporting System database.

Moreover, the OECD classifies ODA spending simply as having been allocated either to crop, livestock or fish production. This makes it impossible either to disentangle investments in protein crops such as legumes from funding allocated to the production of crops such as fruits and vegetables or to distinguish investment in wild capture fisheries from funding allocated to aquaculture projects. Taken together, these constraints mean that some relevant funding streams are likely to be poorly represented in official datasets. It is therefore difficult to estimate the total quantity of ODA funding invested in protein production accurately and that the figures presented above may underestimate the total quantity of investment provided by development finance actors.

Even less data relating to private sector investment in protein production is available due to the legal organisation of the private sector actors which are most prominently involved in financing African agriculture (Watts and Scales, 2020). Investment by international agribusinesses in the protein production operations of their African partner firms or subsidiaries is likely to be subsumed into broader categories of expenditure in their public financial reports and accounts, making it difficult to estimate the size of their investments in protein production. Alternatively, their operations in sub-Saharan Africa may be administered through subsidiaries or holding companies which produce separate accounts, meaning that investment in these enterprises does not appear in the parent company’s public financial disclosures at all.

Meanwhile, sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural and food sectors are dominated by privately owned companies and informal enterprises which are subject to far more limited financial disclosure requirements than are shareholder-owned corporations which are listed on stock exchanges. As a result, little information is available in the public domain about the holdings of most private equity firms or the size of their agricultural investments (Ouma, 2020). Given that 75% of the agricultural investment funds focusing on Africa are private equity funds, while listed equity funds make up a negligible proportion of the market, this severely limits the availability of public data on equity investments on the continent (Valoral Advisors, 2018). Likewise, while commercial banks will typically release publicly available annual financial reports, these documents rarely disaggregate their lending sufficiently to establish how much money they have invested in the agri-food sector. Although commercial providers of financial data maintain proprietary databases recording both private equity investment into emerging markets and commercial banks’ lending activities, the author did not have funding to secure access to these resources and was thus unable to make a robust estimate of the size of private sector financial flows into protein production in sub-Saharan Africa.

In summary, much remains unknown about the landscape of investment in protein production in sub-Saharan Africa including the total quantity of capital invested and the identities of the largest individual providers of funding. However, if wider patterns of investment in African agriculture are replicated then the most prominent sources of investment are likely to be public sector expenditure by national governments and foreign direct investment by international agribusiness corporations. Multilateral and bilateral development assistance, along with philanthropic investment, might be expected to account for a considerably smaller but still significant proportion of investment. It is probable that private equity funds and commercial banks are the most prominent private sector investors in protein production in sub-Saharan Africa, but that they supply only a small proportion of its total funding. Meanwhile, the contribution of investment made by private individuals, families and small businesses is poorly captured by official datasets and remains impossible to estimate.

References

-

African Development Bank Group (2016) Feed Africa: Strategy for agricultural transformation in Africa 2016-2025. Abidjan: African Development Bank Group. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents…

-

African Development Bank Group (2021) Livestock Investment Master Plan. Abidjan: African Development Bank Group. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/…

-

FAO (2022) Credit to agriculture: Global and regional trends 2012-2020. Rome: FAO. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/cb8790en/cb8790en.pdf

-

Ouma S (2020) Farming as Financial Asset: Global Finance and the Making of Institutional Landscapes. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing.

-

Valoral Advisors (2018) 2018 Global Food & Agriculture Investment Outlook. Luxembourg: Valoral Advisors. Available at: https://www.valoral.com/wp-content/uploads/2018-Global-Food-Agriculture…

-

Watts N and Scales IR (2020) Social impact investing, agriculture, and the financialisation of development: Insights from sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 130: 104918. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104918.

Post a new comment »