Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa:

- Introduction

- Background

- Research Methodology

- Sub-Saharan Africa’s Agricultural Investment Landscape

- Investor Visions

- National Subsidies and Global Market

- Conclusions

- Glossary

Suggested citation:

Brice, J., (2022) Investment, Power and Protein in sub-Saharan Africa. TABLE Reports. TABLE, University of Oxford, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Wageningen University and Research. doi.org/10.56661/d8817170

Summary

- The ‘smallholder intensification’ vision was held by a network of philanthropic organisations, development finance institutions and impact funds pursuing shared development goals including poverty reduction, the reduction of malnutrition, and the pursuit of sustainable development.

- These investors sought to address poverty and malnutrition among smallholder farmers and pastoralists by increasing the productivity of their livestock. They therefore invested in companies supplying agricultural inputs such as veterinary medicines, animal feeds and breeding stock to small producers.

- They also financed enterprises (such as dairy and meat processors) which purchased animals or animal products from smallholder farmers before selling them on to commercial buyers or processing them into higher value products. These investments were intended to help small-scale livestock producers to secure higher prices for their produce by connecting them to more lucrative markets for processed animal products.

- Due to concerns about the environmental impacts of livestock production, most of these investors preferred to finance initiatives designed to increase the quantity of protein produced per animal rather than ones which would expand the number of animals kept by small producers. Most also avoided investing in beef production due to concerns about the greenhouse gas emissions produced by ruminant animals, and instead focused on financing dairy, poultry, egg and (to a lesser extent) aquaculture value chains.

- These investors often invested deliberately in countries and companies which purely commercial investors would consider either too risky or insufficiently profitable to finance in order to reach the poorest and most marginalised producers. As a result, they invested across much of Eastern and Southern Africa (e.g. Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia), as well as larger West African markets (e.g. Nigeria and Ghana).

- In these locations, their investments aimed to foster a distinctive value chain structure in which most animal protein is produced by smallholder farmers and pastoralists. However, these small producers are increasingly sandwiched between larger producer cooperatives or privately owned agricultural input suppliers and larger aggregators and processors which connect them to higher value markets for their produce. As such, they envisioned a future in which small-scale livestock agriculture was anchored by larger organisations acting as ‘hubs’ for the (relatively) large-scale provision of agricultural inputs, extension services and (in some cases) access to higher value markets.

Who?

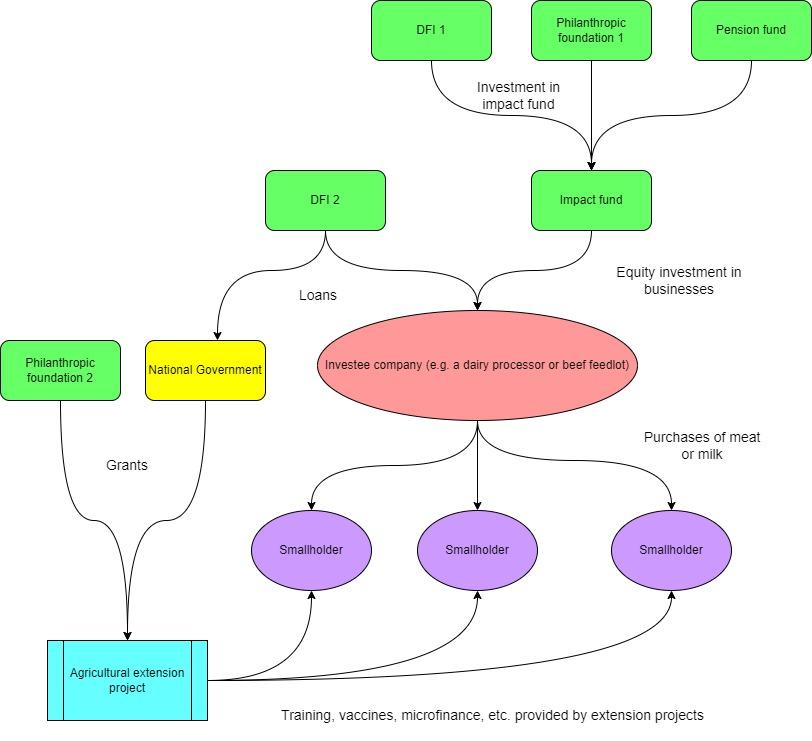

The first of these three investor visions was shared broadly by philanthropic organisations, development finance institutions and impact funds, some of which regularly partnered with one another to invest in the same initiatives. For instance, as illustrated in Fig. 11, a DFI and a philanthropic foundation might both contribute funding to an agricultural development project or to an impact investment fund with agricultural development and food security objectives. These collaborations required agreement on the objectives of the investment, and thus reflected the existence of (and may have helped to consolidate) a shared approach to investment in protein in sub-Saharan Africa among this network of investors.

Figure 11: Example Smallholder Intensification Investment Network.

This diagram outlines the various arrangements through which members of the smallholder intensification investor network might finance animal protein production in sub-Saharan Africa. For illustrative purposes it seeks to depict all the routes through which investment might be provided and does not represent the arrangements through which any specific enterprise or value chain is funded.

One cluster of investors (DFI 1, Philanthropic foundation 1 and a pension fund) invest in an impact fund, which pools their capital and uses it to purchase shares in companies such as dairy processing companies or beef feedlots. These investors thus become indirect owners of a portion of these companies.

A second cluster of investors (DFI 2 and Philanthropic foundation 2) instead funds agricultural extension services which are provided on a non-commercial basis - either via direct grants (in the case of the philanthropic foundation) or via loans to a national government (in the case of the DFI). This agricultural extension project provides support to smallholder farmers in the form of funding for training, veterinary medicines or microfinance services. These farmers may then sell meat or milk to the processing company, enabling them to receive some of the money invested in it via the impact fund (albeit indirectly).

Reflecting this investor network’s varied membership, its members used a wide range of financial instruments. While philanthropic organisations and DFIs have traditionally provided funding in the form of either grants or loans, both groups of investors increasingly also invest capital in impact funds. These impact funds then make equity investments in companies operating within sub-Saharan African protein value chains (Watts and Scales, 2020). For at least some DFIs this provides an important means of financing businesses which are too small to absorb the large loans which they would traditionally have provided:

“Our minimum equity investment is [$]25, 30 million, and our minimum debt’s 20 million plus. That can be viewed as both an advantage or a disadvantage. We hear it from the ground that it’s a bit of a disadvantage because, well, the SMEs obviously are not reachable any more for us. We do route our investments through funds, specialist funds (...) that are focused on a particular sector. And that allows us to pepper our investment sizes to a lower quantum.”

(Interview 19, DFI)

Some of the impact funds whose staff were interviewed had also partnered with philanthropic organisations and DFIs to provide grant-funded agricultural extension and community development services to small producers within their investee companies’ supply chains. The quantities of funding invested by these different actors in any given project and the financial instruments through which they were provided might vary (and could become complicated to trace in the case of larger projects). However, the range of organisations involved, and the values and objectives which animated their investment programmes, remained fairly consistent across different countries, livestock species and sections of protein value chains.

Why?

All of these investors tended to be motivated by a common set of development goals including:

- The reduction of poverty;

- The reduction of malnutrition; and

- The achievement of these goals in a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable fashion (i.e. sustainable development).

Each organisation’s investments were intended to advance all three of these goals, often alongside further closely related objectives such as the promotion of gender equality. These investors argued that investment in protein production in sub-Saharan Africa should be targeted at initiatives which would improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers and pastoralists for two reasons. First, they suggested that for many rural households poultry, cattle and small ruminants such as goats already serve as a store of wealth which can be drawn upon through selling animals during periods of economic stress. As such, investments in these livestock species were deemed to be particularly effective in increasing both the household incomes and the economic resilience of the rural poor.

Second, interviewees frequently highlighted that smallholder farmers and pastoralists are among the poorest and most socio-economically marginalised populations within African countries and therefore often suffer disproportionately from malnutrition. As such, they expected that investing in increasing their capacity to produce animal protein would reduce rates of malnutrition through increasing their dietary protein intake. Such investments might produce this effect directly through enabling small producers and their families to consume larger quantities of animal products which they had produced themselves or indirectly through enabling them to use money earned by selling a larger volume of animal products to others to purchase a greater variety of foodstuffs.

“We wanted to increase productivity. If you really make sure that the markets are functioning and they can monetise their produce, that will drive the household income as well as improved nutritional outcomes. Both in terms of, you know, if they are increasing productivity, they will have surplus to consume (...) but also by monetising it they can drive dietary diversity. You know, they don’t have to depend on their own production to consume.”

(Interview 07, philanthropic foundation)

This group of interviewees was acutely aware of the environmental impacts of livestock production and regularly discussed their concerns about the greenhouse gas emissions associated with ruminant animals, the potential impacts of overgrazing on rangelands and the land conversion footprint of animal feed production. Due to these environmental considerations they preferred to finance initiatives designed to increase the quantity of protein produced per animal rather than ones which would expand the number of animals kept by small producers. Some such interviewees suggested that their programmes were designed to drive a ‘culture change’ in which small producers would move away from considering their animals a store of wealth (and seeking to acquire larger herds) towards treating them as a revenue stream and attempting to maximise their income by growing and selling animals more quickly. This, they argued, would prevent the total number of animals from increasing.

Interviewees therefore often argued that focusing on increasing the productivity of livestock enabled their investments to contribute both to providing greater economic security for small producers and to satisfying sub- Saharan Africa’s growing demand for animal protein without causing a commensurate increase in the negative environmental impacts of livestock agriculture. Some interviewees provided examples of past projects funded by their organisations which had achieved this goal of increasing livestock productivity without precipitating a significant expansion in the size of the herds kept by the producers involved, although they acknowledged that any given investment’s ability to achieve this outcome could only be evaluated retrospectively.

“Through climate funds it is possible to access money to finance livestock projects, but with some very strong caveats they put in the spec. A project in which the yield per animal will increase (...) so you can produce 1,000 litres [of milk] with less animals (...) [which] means less greenhouse gas emissions, that’s more attractive for a climate fund like GEF [the Global Environment Facility], GCF [the Green Climate Fund]. Rather than building the story that we’re going to produce 1,000 litres through more dairy cattle. That will not go through the finance.”

(Interview 10, DFI)

What and Where?

These investors’ emphasis on environmental sustainability also led them to focus their funding on particular livestock species. Several interviewees highlighted that while financing for cattle farming had long been a prominent component of both DFIs’ and NGOs’ agricultural development programmes in Africa (de Haan et al., 2001), it was becoming increasingly difficult to obtain finance to support new projects to support smallholder farmers raising beef cattle. These interviewees suggested that this shift reflected concerns over the climate impacts of methane emitted by the digestive systems of ruminant animals and the high carbon intensity of beef production:

“We only have one [beef] cattle project. And (...) we try to encourage the people not to grow their herds. It’s to have the same size herd but more turnover, so a more efficient herd. More calves, less mortalities and therefore more sales per annum on the same size herd. (...) I’m not sure we would do it again. It’s just so difficult with the climate issue. But where we have done it, it has created a huge impact, a positive impact, social impact. It’s just – I think it’s quite difficult now. It’s quite difficult to mitigate the climate impact.”

(Interview 16, private equity investor)

As a result, while some interviewees argued that investment in beef cattle could benefit small producers through making their livelihoods more diversified and resilient, increasing household incomes and improving nutritional health, most had shifted their focus towards poultry and egg production and towards the raising of cattle and small ruminants to produce dairy products(2). This pattern of financing (with the possible exception of investment in dairy production) is consistent with the Joint Multilateral Development Bank Assessment Framework for Paris Alignment for Direct Investment Operations (African Development Bank Group et al., 2021), which classifies investment in fishing, aquaculture and non-ruminant livestock agriculture as being universally aligned with the Paris Agreement’s climate change mitigation goals. As such, it may in part reflect the Framework’s influence on DFIs’ investment decision-making.

Some interviewees highlighted that these environmental concerns – combined with the emergence of new evidence about the economic and nutritional benefits of aquaculture – had also driven increased interest in investment in small-scale aquaculture projects. However, while aquaculture projects had as a result assumed an increasingly prominent role within some DFIs’ investment programmes, other interviewees suggested that they had struggled to find aquaculture projects which were large enough in scale to be investable. Some were also reluctant to finance aquaculture enterprises due to the failure of previous investments, with one interviewee highlighting that aquaculture projects could easily fall victim to disease if those involved in them were not already skilled in fish farming and did not have access to healthy breeding stock. As a result, while these investors displayed enthusiasm for investment in aquaculture, a larger proportion of their investment still appeared to be directed towards poultry, egg and dairy value chains.

These investors’ objectives of improving the economic and nutritional wellbeing of smallholder farmers led them to focus their investments on two types of enterprises. First, most such organisations invested in companies supplying high-quality agricultural inputs such as veterinary medicines, professionally mixed animal feeds and higher yielding breeds of animals(3) in the hope that making these products more affordable and available would increase the productivity of small-scale livestock producers. Second, some invested in enterprises which purchased animals or animal products from smallholder farmers and aggregated them for sale to commercial buyers or processed them into higher value products. Investment in this second group of enterprises (described variously as aggregators, offtakers or processors) was intended to ‘connect’ small producers to more lucrative markets for processed animal products, and thus enable them to secure a higher price for their produce.

This dual emphasis on replacing domestically produced breeding stock and animal feed with commercial agricultural inputs, and on encouraging smallholders to sell their produce via food manufacturers, retailers and foodservice enterprises operating within the formal economy instead of local informal markets, situates the smallholder intensification vision firmly within the ‘value chain’ approach to agricultural development. Promoted by prominent international development actors such as the World Bank Group since the late 2000s, value chain approaches are distinguished by their belief that poverty and low productivity among smallholder farmers results from isolation from formal markets in which buyers are willing to pay higher prices for agri-food products. They thus tend to focus development institutions’ attention and investments on facilitating the inclusion of small producers into a ‘chain’ of formal enterprises – from input suppliers and processors to retailers – capable of connecting them both to manufacturers of high-quality agricultural inputs and to urban or international consumers capable of paying a higher price for their produce (McMichael, 2013).

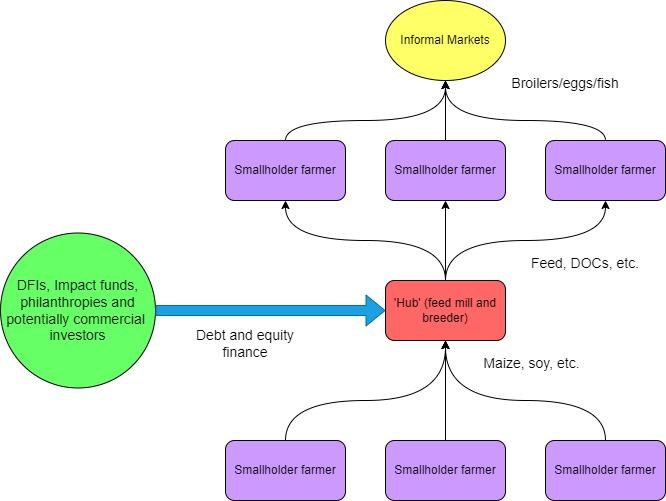

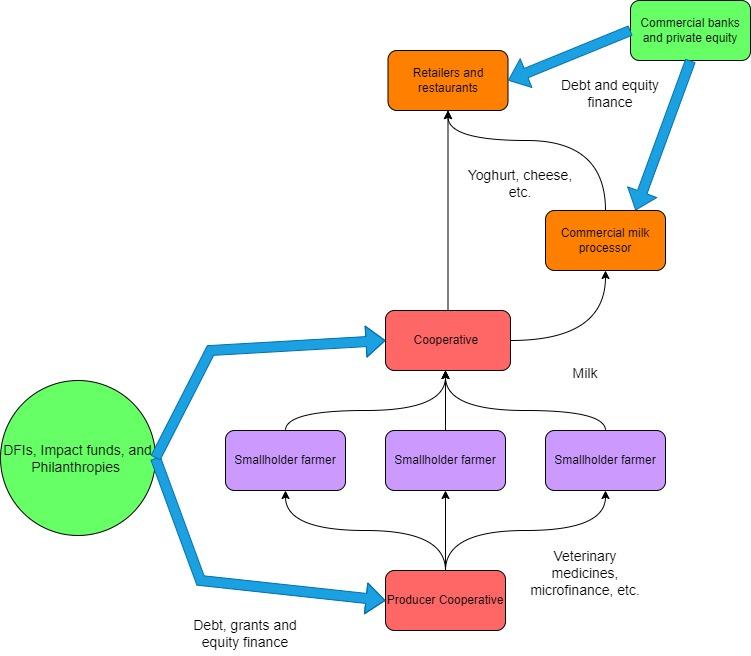

The types of enterprises which these investors considered most vital to creating these new agricultural value chains, and thus the focus of their investments, varied between different livestock species. As Fig. 12 illustrates, investment in poultry and egg production tended to focus on companies operating feed mills (which usually sourced the crops used in their feed from local farmers), because a lack of appropriately formulated poultry feed was considered to limit the productivity of smallholders’ birds. These firms often also bred, hatched and vaccinated day-old chicks (DOCs) for sale to smallholders who then reared them for meat and/or egg production. Smallholders who purchased DOCs from these companies were expected to sell both birds reared for meat and the eggs produced by layer birds within local informal markets.

Figure 12: Destination of Smallholder Intensification investment: poultry, egg and aquaculture value chains.

Figure 13: Destination of Smallholder Intensification investment: dairy value chains.

These investors often invested deliberately in countries and companies which purely commercial investors would (as discussed in the next section) consider either too risky or insufficiently profitable to finance. In doing so, they hoped to produce a greater positive impact both through benefitting the poorest and most marginalised producers and through enabling agricultural enterprises with limited access to other sources of finance to establish themselves and expand. This imperative to maximise the ‘development impact’ of their investments did have to be balanced against the risk that projects in the most politically and economically fragile countries would fail due to conflict or political instability, a lack of reliable markets for animal products or events such as environmental shocks. However, these investors’ relatively high tolerance for risk had enabled them to apply this investment approach across much of Eastern and Southern Africa. By contrast, some interviewees had avoided investing in West and Central Africa (with the exception of larger West African markets such as Ghana and Nigeria) because they perceived many countries within these regions as presenting riskier and more challenging business environments for investors for reasons including conflict, poor governance and political instability.

“Relatively speaking we operate in more fragile economies than the other financial institutions. (...) We obviously go into projects where commercial capital is challenged and our contribution is [to] provide catalytic capital that down the road will help mobilise further capital. But there are some countries that stand out more than others that we really want to do – big change in Nigeria, for instance, but it also happens to be one of the most challenging economies to do business in. We’re keen on Nigeria. Egypt’s also an area we need to do a lot more in, Kenya, Tanzania. (...) it’s that growth potential, the size of the development impact. If you look at Nigeria, for instance, [it’s] 200 million people with 30 per cent unemployment and maybe half the population living below the poverty line. So it’s a very strong case for us to be there.”

(Interview 19, DFI)

In these locations, their investments appeared to be designed to produce a distinctive value chain structure. In the value chains envisioned by such investors most animal protein is produced by smallholder farmers and pastoralists. However, these small producers would be sandwiched between larger agricultural input suppliers (in the form of producer cooperatives or privately owned companies) providing agricultural extension services, and larger aggregators and processors connecting them to higher value markets for their produce.

Interviewees identified the poultry feed and input supply sectors in countries such as Zambia, Tanzania and Uganda as having undergone the forms of growth and consolidation associated with this investor vision – with a small number of firms (often financed initially by DFIs and/or impact investors) now supplying most small poultry farmers. Meanwhile, they suggested that dairy cooperatives had become particularly established in East African countries such as Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia, with a few attracting thousands of members and growing large enough to develop their own processing plants and brands of milk products. Small-scale livestock agriculture was thus anchored by larger organisations which acted as ‘hubs’ for the provision of agricultural inputs, extension services and (in some cases) access to higher value markets in what some interviewees termed the ‘hub- outgrower model.’

How?

This group of investors’ shared theory of change can be summarised loosely as follows. Adherents of the smallholder intensification vision believe that smallholder farmers and pastoralists currently lack access both to high quality agricultural inputs and to formal value chains which are capable of connecting them with customers who will pay an attractive price for their products. They therefore either keep their animals primarily as a store of wealth or sell the foods which they produce at low prices via local informal markets. Because these animals grow slowly and live for a long time, large quantities of land and feed are required to produce each unit of animal protein. In consequence, such investors argue, these production systems are economically and (more importantly) environmentally inefficient.

Adherents of the smallholder intensification vision argue that investing in providing small producers with easier and more affordable access to high quality agricultural inputs will enable their animals to grow more quickly and to produce more meat, milk and eggs. This will improve small producers’ nutritional health by increasing their household incomes and/or domestic consumption of animal protein. Meanwhile, investment in enterprises which connect small producers with higher value markets – such as cooperative-owned milk aggregation stations and processing plants or beef feedlots – will enable them to realise more value per unit of animal protein produced.

This will increase both the productivity of small producers’ animals and the value of their products. It will thus enable them to reinvest either in further increasing the productivity of their animals or in meeting other household expenses such as school fees for children.

Such investors therefore suggest that these investments will reduce both malnutrition and poverty, while enabling small producers to secure and improve their existing position within sub-Saharan African economies and food systems. They will also reduce the quantity of land and feed required to produce each unit of animal protein because animals will live shorter lives and convert feed more efficiently into protein. As a result, they will enable more animal products to be produced to satisfy expected future growth in sub-Saharan Africa’s appetite for protein without creating a commensurate increase in the environmental footprint of animal agriculture.

Footnotes

2 Because ruminant animals kept for dairy production yield milk continuously throughout their lives, these animals emit a smaller quantity of GHGs per unit of protein produced than beef cattle.

3 Several interviewees acknowledged that the use of land to produce this animal feed would inevitably produce negative environmental impacts of its own, and some tried to mitigate these through using locally sourced feed crops grown by smallholder farmers on existing agricultural land in rotation with their established crops. In so doing, these investors hoped to avoid the use of animal feed produced from commodities such as soy which might be implicated in driving land conversion elsewhere in the world. These interviewees did not claim that this entirely nullified the impact of introducing more feed-dependent breeds of animals. However, they suggested that in combination with the efficiency and productivity gains enabled by higher yielding animal breeds it reduced them to a level which was acceptable given the benefits of their investments to both producer livelihoods and nutrition.

References

-

African Development Bank Group, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, et al. (2021) Joint MDB Assessment Framework for Paris Alignment for Direct Investment Operations. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank. Available at: https://www.eib.org/attachments/documents/cop26-mdb-paris-alignment-not…

-

de Haan C, van Veen T, Brandenburg B, et al. (2001) Livestock Development: Implications for Rural Poverty, the Environment, and Global Food Security. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14006/multi0…

-

McMichael P (2013) Value-chain Agriculture and Debt Relations: contradictory outcomes. Third World Quarterly 34(4): 671–690.

- Watts N and Scales IR (2020) Social impact investing, agriculture, and the financialisation of development: Insights from sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 130: 104918. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104918.

Post a new comment »