Sparing, sharing or something in between: what are the implications for biodiversity?

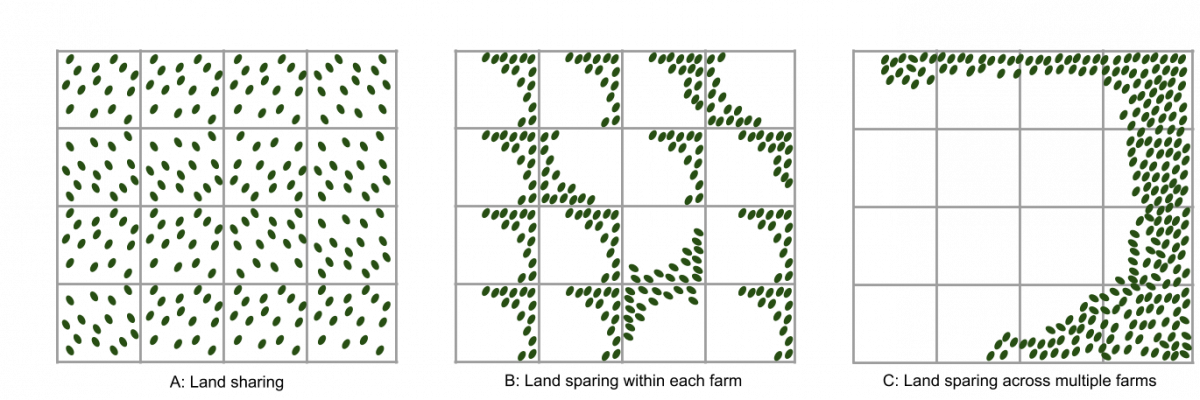

Decisions about land use are based on many factors on top of biodiversity, including, in particular, economic considerations. Addressing these multiple considerations requires context specific approaches to land use and in practice, most current landscapes are not exemplars of the extremes of the land sparing-sharing continuum, but rather represent mixed and intermediate scenarios.

An example of an intermediate scenario would be arable field margins, where some native vegetation is protected (meaning at least some increase in species diversity) but at slight cost to yield. A mixed scenario might involve using an area of land both for conservation and low-yielding farming (e.g., conservation grazing), alongside a smaller area of high-yielding farmland.

Whether land sparing or land sharing is least costly to biodiversity depends on many factors, including the range of different species present, landscape features like topography, climate and previous land use, the farming techniques used, and the specific crops or livestock being farmed. A further complication is that the way biodiversity is measured can vary – it can be understood as the number of different species present in an area (species richness) but also as the size and viability of species populations (species abundance). People also have different values and opinions as to which species to prioritise in biodiversity conservation efforts (e.g., endemic species or those that fulfil important functions such as pollination). Judgements are further influenced by various scientific or lay arguments and perspectives on human- nature relationships. This complexity makes it difficult to conclude which land use strategy is theoretically optimal in different contexts.

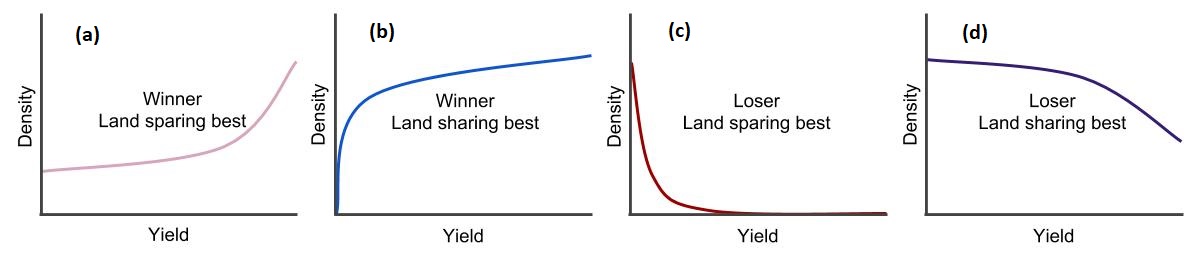

Most empirical studies comparing land sparing and land sharing have been undertaken by conservation biologists from the University of Cambridge. These studies use data on the densities of specific wild species across a gradient of agricultural yields, from unfarmed land to high-yielding farmland, to develop density-yield curves (figure 2) that illustrate if the population of a given species would be greater under land sparing or land sparing.

Despite looking at very different landscapes (e.g., tropical forests or European farmland) these studies all reach very similar conclusions. Some species (so-called ‘winners’) have higher densities in farmland than in natural, zero-yielding habitat (figure 2a and b). However, the populations of most species (so-called ‘losers’) decline when their habitats are converted to farmland (figure 2c and d). This is particularly the case for specialist and/or endemic species which need very specific environmental conditions and so are most negatively affected by conversion of wild land to farmland. Since many of these species are often of greatest relevance to conservation efforts, a general observation for the landscapes considered by these studies is that land sparing may be preferable to land sharing for supporting viable populations of more species.

Overall, two conclusions arise here. First for agricultural production to rise (the need for this is debated – see below) then increasing yield rather than converting more wild areas to farmland would be less detrimental for biodiversity. Second, to ensure land sparing does occur (see below) protected areas for endangered species must be established and/or enforced.

Figure 2 : Different common density-yield curves. Density refers to the density of the population of a species per unit of farmland. Yield refers to yield per unit of farmland. Adapted from Phalan et al. 2011.

Comments (0)