Games at TABLE will soon be launched as the first food-systems-focused serious games library to encourage future project collaborations and support food system education, research, and broader transformation. Serious game expert Federico Andreotti provides an overview of serious games around farming and food systems, with three examples of existing serious games designed by students at Wageningen University.

Federico is a lecturer and researcher at Wageningen University. He is the game expert of the CiFoS research team, and coordinator of the WUR Games Hub that connects multiple researchers that use games to bridge science and society. Federico’s PhD project was on the co-design and application of serious games for the sustainability transition of farming and food systems; his current research and education focus is on games design and play and participatory research methods to explore futures farming and food systems. Via “Games at TABLE” he aims to foster an international community connecting game researchers and designers across the globe, encompassing social sciences, natural sciences, and design. These partnerships may serve to develop effective strategy games and engage players with agency: decision makers who play and take action to transform systems.

Open call for collaboration and game ideas

Have an idea for a food system game or serious game project?

As part of a new partnership with TABLE, we are launching a shared food systems games library (featuring the three student-designed games described above) hosted on TABLE’s website. We invite ideas and collaboration opportunities for new and ongoing game projects which encompass all the aspects of the food system, with the aim to support education, research, and broader food system transformation.

Feel free to reach out, if you are planning an event or if you want to showcase or write about a game you have developed: federico.andreotti@wur.nl

Serious games

Games have always provided entertainment, but what if a game could also serve as a way to tackle challenges? Such games are called "serious" because they offer more than just amusement. Clark Abt is credited with coining the term "serious games" in the 1980s, defining them as games that have an "explicit and carefully thought-out educational purpose and are not intended to be played primarily for amusement." Since then, serious games have been used in research and education to help players learn about, discuss, and explore complexity.

By playing a game that simulates part(s) of a real-world system, participants can explore the potential impacts of their actions while sharing their knowledge and understanding of how the system functions. Serious games allow researchers and practitioners to connect multiple disciplines and integrate knowledge with design thinking, creating opportunities to explore and engage with complex systems.

These types of games can take various forms, including card games, video games, board games, and narrative-driven experiences such as storytelling or choose-your-own-adventure games. Furthermore, co-designing games with stakeholders or students has become a common practice in universities and action research projects.

Can serious games facilitate dialogue around the redesign of farming and food systems?

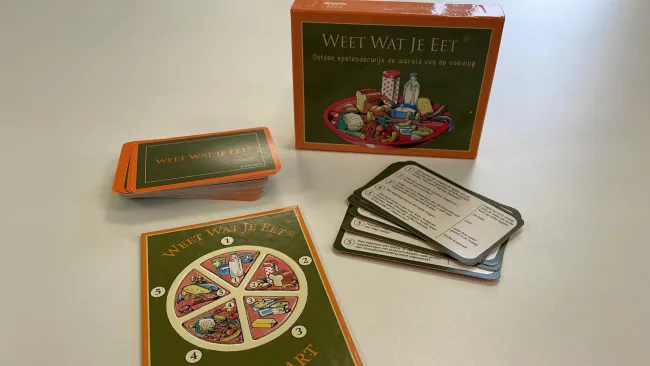

Serious games have been widely used to engage stakeholders in reflecting on food systems. A few years ago, I walked into a second-hand shop in my hometown, Wageningen, and came across a a serious game about food systems titled Know What You Eat, featuring the university’s logo on the side. This quiz game, released in 1995, contains 280 questions and answers about food and drinks.

Know What You Eat is a simple game for 2 to 4 players and challenges participants to reflect on their eating habits, health, and culture to foster learning and reflexivity. Over the past 30 years, more and more food system games have been developed and evolved to incorporate more complex food system components, from farm to fork, and explore a broader range of cultural aspects, biodiversity, land management, and more.

Modern games have been used to help formulate and challenge food system visions. They allow players to examine problems from different perspectives while also imagining and constructing potential — perhaps even desirable – futures (Resource, 2024). Defined as interactive simulations where players make decisions to achieve specific objectives, games provide a dynamic way to research and engage with complexity (Garcia et al., 2022). By simulating evidence-based scenarios, participants engage with a game rooted in their socio-economic context, experiencing system dynamics and assessing the impact of their actions. This approach fosters dialogue, enhances communication, and reveals participants’ needs and values, helping to build consensus on the necessity of system transformation. These playful tools are useful for bridging the science-policy interface and effectively engaging decision-makers.

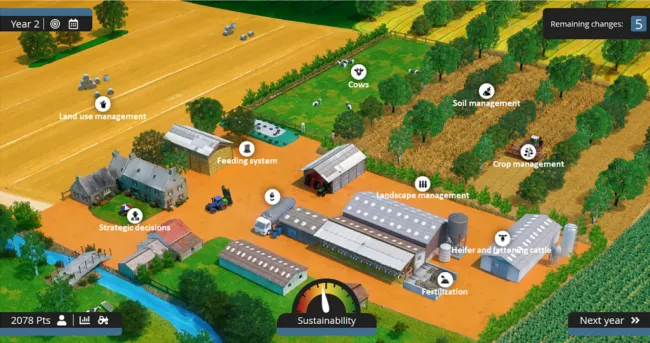

SEGAE (see Figure 2), a more modern, well-known, online, simulation game , was designed to help players learn about the environmental, economic, and social pillars of agricultural sustainability. It was developed to support agroecology education, particularly in European agricultural programs, where teaching its diverse practices remains a challenge. Players engage in scenarios that enhance their understanding of soil health, sustainability trade-offs, and strategies for transitioning to organic farming. The game’s outcomes encourage discussions on organic certification processes and the sustainable integration of crop and livestock production, covering both farming and food system aspects (Jouan et al., 2021).

While many games focus on specific components of food systems, holistic games remain rare. Such games are valuable, however, because they have the potential to foster system transformation, which is essential for radically redesigning today’s farming and food systems to explore both human and planetary health, now and in the future. Achieving this paradigm shift requires consensus among stakeholders on the solutions needed for food system redesign, a daunting task which holistic serious games can facilitate.

For more information on the transformative potential of holistic games, I recommend these two recent key review articles:

- A sustainable game changer? Systematic review of serious games used for agriculture and research agenda (Dernat et al., 2025)

- A leverage point perspective on serious games for sustainability transformation: a systematic literature review (Foppe & von Wehrden, 2025)

Food system games in higher education

Higher education provides an opportunity to explore the utility of serious games, moving beyond the traditional lecture-based teaching methods that have persisted since the earliest days of universities (see Figure 3, for example, depicting a 1350 illustration by the artist Laurentius de Voltolina of a class at the University of Bologna).

Even at that time, something seemed wrong. If you look closely at the third row, you can spot a student sleeping, emphasizing the long-standing need for more interactive and engaging ways to teach. At Wageningen University, we address this challenge in the course Redesigning Global Farming and Food Systems (FSE32306). Students learn the principles and applications of various cross- and transdisciplinary approaches to analyze and redesign food systems. They also explore how to translate scenarios and both qualitative and quantitative data into the design of serious games, using them as discussion-support tools for food system transformation (see Figure 4). This programme is done in collaboration with the WUR Games Hub with Federico Andreotti (FSE, WUR), and Stefan Werning (Utrecht University). The students have the chance to finalize their serious game design – e.g. in the form of a collaborative boardgame – using the facilities of the Playground at Utrecht University and of the DesignLab at Twente University guided by Robert-Jan den Haan.

Over the last three years, students have designed multiple serious games to reassess global farming and food systems. The course ended with a final interactive event in which external participants were offered the opportunity to play these serious games exploring futures farming and food systems (Figure 4). The outcomes of this session were also presented at the Dutch Design Week during the “Climate Futures Now!” debate.

Check out this brief video from WUR Games Hub of the "Climate Futures Now!" event.

Three more examples of student-designed games include: Aridia – droughts in Andalucia, Harvest Havoc, and Who Got the Power? The games booklet description and materials will be available in the Games at TABLE library.

- Aridia – droughts in Andalucía

This board-game follows three olive farmers in southern Spain facing increasing water scarcity over time. Each farmer uses a different irrigation method, one maintaining high water use, one adopting a moderately efficient system, and one using the most water-saving approach (Figure 5). The game highlights the impact of farming practices on a landscape experiencing worsening droughts. Initially, water is abundant, but event cards progressively limit its availability until it runs out, ending the game and leading to a debriefing. The game aims to raise awareness of water as a shared, finite resource. While early designs focused on individual profit and collective water sustainability, the final version is more scripted, illustrating the consequences of conflicting priorities in a water-scarce future.

- Harvest Havoc

Many nations rely heavily on imported food for diversity and affordability, but this dependence makes them vulnerable during conflicts abroad. Such conflicts can disrupt production, block transport routes, and reduce food availability, affecting global markets and prices. To address these sudden challenges, strategic planning is essential to safeguard food security (see Figure 6).In this game, players govern a fictional country, working to ensure food security for their population while navigating the impact of conflicts. Beyond their own survival, they can also support other nations, acknowledging that some face greater struggles due to their unique circumstances.Through gameplay, players will explore how conflicts affect food security and biodiversity. They will experience how instability disproportionately impacts less stable or resource-scarce countries while also recognizing the indirect effects on wealthier nations, including shifts in migration patterns.

- Who got the power?

Who Got the Power? is a discussion-based board game exploring land use change in the Brazilian Amazon. Players take on the roles of five key actors: the Brazilian farmer, the Brazilian government, the rainforest, the beef export lobby, and international environmental policies. The game highlights how collective decisions shape land use, balancing agricultural expansion, rainforest conservation, and livelihoods. The main challenge for players is to understand how their decisions impact land use over time. Power dynamics are initially assigned at random and later shift based on in-game events and resource thresholds, altering each actor’s influence in decision-making. Designed for five players, the game engages stakeholders involved in Amazon land use debates. Setup takes 5–10 minutes, and a full session lasts about 30 minutes (5–6 rounds), followed by a 15–20-minute debrief. There is no set win condition; instead, the game ends when the final round concludes, prompting reflection on power shifts and outcomes. The game’s primary objective is to examine power relations and how shifting influences among stakeholders affect land use decisions in the Amazon.

Interested in learning more about these games?

Have a closer look at some serious food system games, developed by students at WUR Games Hub

The downloadable booklets include explanations, instructions and component descriptions for each food system game.

Comments (0)