The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona is a microcosm of the current international movement towards increasing urban food self-sufficiency, with the aim of promoting both supply chain resilience and social justice. In this blog post, Haley Parzonko reflects on the challenges and opportunities facing the urban agriculture movement in and around Barcelona.

Haley Parzonko has just finished a master’s degree in Political Ecology, Degrowth Economics, and Environmental Justice at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. She will soon start a PhD at the University of Surrey focusing on local food systems. Her research interests focus on the intersection between urban food systems, social justice, and environmental sustainability.

Introduction

Since the signing of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact in 2015, food has been placed at the core of urban agendas across many countries, particularly improving urban food self-sufficiency. The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (henceforth AMB) is a microcosm of the current international movement towards increasing urban food self-sufficiency, understood here as the extent to which a given city can fulfil its food demand from domestic production. To this end, one main strategy to increase a territory’s food self-sufficiency is urban agriculture: the cultivation of agriculture in and around cities.

Two main arguments are made in favour of attempting to increase urban food self-sufficiency. First, there has been a growing concern regarding the resilience of food systems as recent crises have exposed the vulnerabilities and precariousness associated with an over-reliance on concentrated international markets (i.e., Russia and Ukraine with wheat) for urban food security. Food system scholars such as Jennifer Clapp have argued that achieving food security requires finding a balance between diverse scales of food production. There is also an argument that urban food self-sufficiency can offer some forms of resilience to cities themselves, such as mitigating rising temperatures and increasing biodiversity and green spaces (for a more comprehensive review see this study) as well as increasing access to healthy food, building social cohesion, and improving educational opportunities (for a more comprehensive review see this study).

Another argument made to support increasing urban food self-sufficiency has a social justice bent. Environmental justice advocates argue that high-income countries such as Spain currently achieve urban food security by unequally shifting the social and ecological costs of primary production to low-income producer countries. Therefore, producing more food domestically in high-income countries can potentially relieve some of the environmental pressures currently placed on resources and labour in primary producing countries in the Global South, allowing those resources to be directed towards their own domestic development.

To investigate the food self-sufficiency capacity and potential of urban spaces, I chose to write about the AMB as a case study for my Masters degree, mainly because of it being an important urban centre in Europe, holding 3.25 million people, and its position at the forefront of European urban agriculture and food strategies. Furthermore, new data from the AMB was released earlier in 2022 on metropolitan-scale agricultural production, granting the ability to investigate metropolitan-level food self-sufficiency.

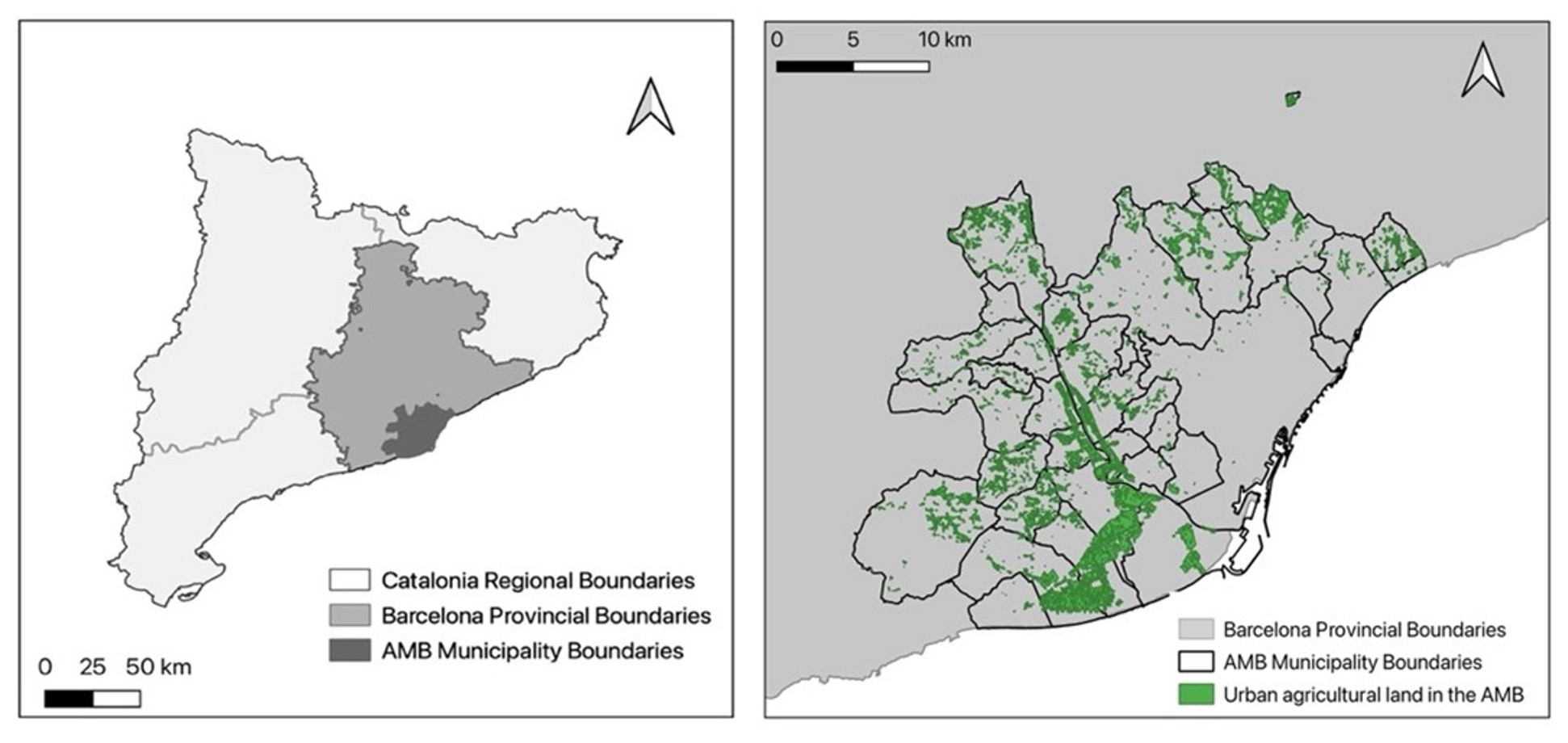

On the left depicts the location of the AMB, sitting within the autonomous community of Catalonia, located in the northeastern region of Spain. On the right is the remaining agricultural land within the AMB for 2015. Figure by Haley Parzonko based on the study by researchers Angelica Mendoza-Beltran and colleagues and the Catalan Institute of Statistics.

Background on the AMB food system

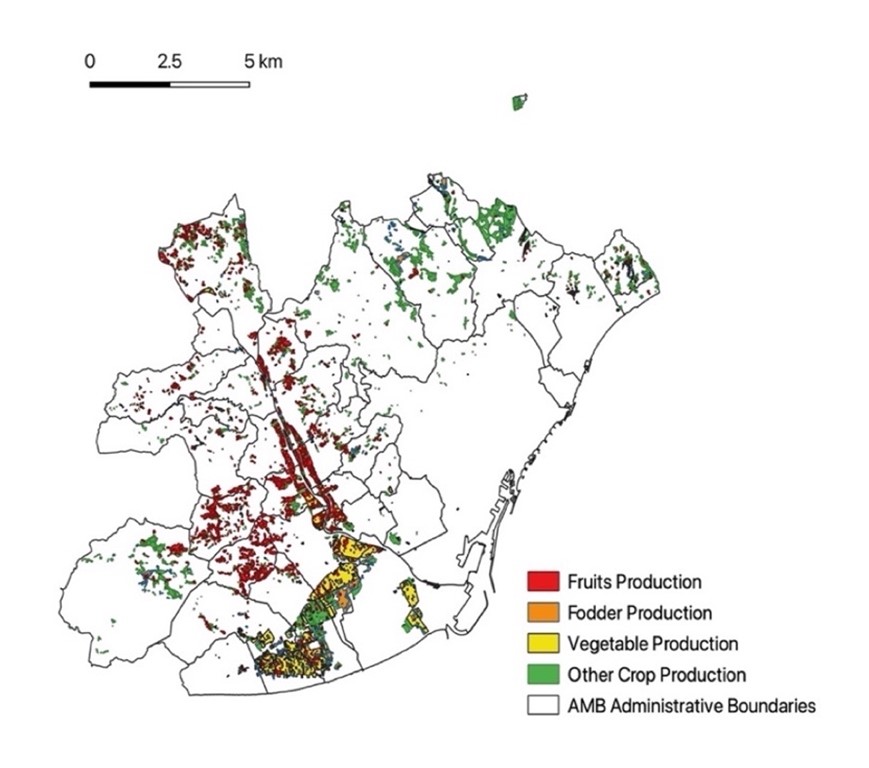

The production of food in and around the AMB has seen major reductions as a result of urban development. From 1956 to 2015, agricultural land has decreased by 77%. The AMB has 636 km2 of land, of which 9% is currently used for agriculture. The crop categories with the highest agricultural output are 38,836 tons of vegetables, 13,186 tons of fruits and 12,859 tons of forage crops such as alfalfa and rye-grass, commonly used as animal feed. A particular diversity of crops is found in the fruit and vegetable categories, with over 35 types being produced. This marks a historical shift in the local landscape away from predominantly producing the Mediterranean trilogy of wine, olive oil, and cereal grains.

A more detailed picture of all the crops produced in the AMB, including 36 municipalities, for 2015 mapped using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Source: Figure by Haley Parzonko based on the study of researchers Angelica Mendoza-Beltran and colleagues.

Consumption patterns in the AMB have also changed dramatically. Much more land is now required to satisfy the demand for food in the AMB, not only due to population increase but also because of dietary changes such as the substitution of traditional foods such as legumes, salted fish and tubers with livestock products. This marks the nutrition transition in Barcelona documented by urban historian Manuel Guardia and colleagues (see also the TABLE explainer What is the nutrition transition?), where livestock products from the 18th century up until the early 20th century have steadily increased their share of overall urban diets coinciding with rising incomes, development of a national market, and improved storage. Currently, according to annual household consumption surveys by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fish, and Food, dairy, eggs, and meat now make up close to a third of the overall diet of AMB residents.

As an example of the mismatch between the AMB’s food production and consumption, if all local food production were to be directed to fulfil local demand in the AMB, then the landscape could provide only 13.7% of total vegetable and 4.8% of total fruit consumption. Other agricultural production in the landscape, such as from olive groves and vineyards, is too minimal to contribute significantly to food self-sufficiency. Most of the locally produced foods are seasonal and therefore the AMB could not currently support local diets all year round.

In short, there have been historical transitions in both the landscape of the AMB and the diet of its population. There is a clear divergence between what, how much and when the landscape can grow and the growing demand for food from residents of the AMB.

The state of urban agriculture in the AMB

Besides the professional farmers in and around the AMB, urban agriculture has spread through many forms in the city. Urban agricultural practices first started gaining popularity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The uprising of civil society motivation to cultivate the city intersected with growing concerns over climate change and the food system as well as urban political struggles over access to land. Others, however, were motivated to grow their own food due to the harsh economic circumstances. Nonetheless, the momentum towards practicing urban agriculture has not slowed, but has diversified to include local authority initiatives, the private sector, and research institutions.

Two main categories that have taken root are urban gardens (i.e., private backyards, vacant lots, individual allotments, on rooftops, squatter gardens, or community gardens) and high-tech urban agriculture (i.e., indoor vertical farming, rooftop greenhouses, or open-air hydroponic systems).

Urban gardens are often thought of as a potential strategy to improve food self-sufficiency due to historical examples, such as the urban gardens in Barcelona which played a central role in urban food security during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). They are often low-tech, solar-powered systems, producing average yields compared to their rural farm counterparts per square metre of land, but have a wide range of reported productivity levels and require more manual labour hours. The bottom-up management of these spaces embodies the principles of food sovereignty, including granting access to environmental resources, being in control of one’s means of production, and being open-access spaces for peer-to-peer learning and sharing agricultural and gardening know-how.

Image: Examples of different urban garden initiatives in and around Barcelona. The left picture represents a community-led urban garden called Desenruna located in the Vallcarca neighbourhood of Barcelona; the right picture shows an individual allotment gardening scheme in Sabadell, which is located in the greater Barcelona region. Photographs by Haley Parzonko.

In contrast, high yields per square metre characterise the high-tech food production systems, but these systems are usually limited to a small variety of crops. These practices have been criticised for the large capital investment required, both financially and in terms of natural resource consumption, to create a controlled growing environment relying on complex infrastructure and high energy use. On the other hand, they have been praised for the efficiency gains they offer relative to conventional field-based agriculture, particularly in water and land use. Furthermore, proponents of high-tech farming often argue that future technological development can lead to even greater efficiency.

Image: Rooftop integrated greenhouse located in the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA-UAB) located at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, shared ownership of the photograph belongs to Sostenipra Research Group who has granted Haley Parzonko the permission to use the photo in this blog post.

As the movement towards urban agriculture continues in the AMB it is important to reflect on the opportunities and challenges within the city. One main opportunity rests within the vacant spaces, either ground-based or rooftops. It was estimated by Barcelona City Council's Environmental Department in 2010 that the potential available space for green roofs was 1,764 hectares within the city. According to another study carried out in 2018 by the Barcelona Provincial Council, there are approximately 911 vacant parcels spread throughout the AMB, offering the opportunity for soil-based urban gardens to expand in these spaces.

Although there are vacant spaces for urban agriculture to use, accessing those spaces requires economic and political support. Recently, prompted by the growth of self-managed urban gardening projects, local authorities in the AMB have promoted small-scale programmes that subsidise publicly owned land for civil society groups or individuals to practice agriculture for a minimal fee, granting land tenure for three to five years. These programmes include the municipal allotment gardening programmes and vacant lot strategies. The high demand and popularity of these programmes show the potential opportunity for more public funding to be directed towards urban agricultural projects in the city.

Access to land for long-term tenure is a main challenge for urban agriculture in the AMB due to high demand, limited land, and unaffordable prices. According to a study by scholar Chiara Tornaghi, not having long-term land security can limit the incentives to invest in the land such as by building soil fertility or growing perennial plants. Due to the high infrastructure costs of high-tech rooftop or indoor commercial farming, they require sizeable public subsidies or private investors to be economically viable. For investors, despite the attraction of innovative farming technological practices, rooftop farming might not offer returns on investment within the timeframe that investors expect.

Despite Barcelona being historically known for its fertile agricultural lands, urban agriculture faces new challenges within the built environment and in the face of climate change. For example, soil-based urban gardens in the AMB are mostly unplanned in the sense that their location is not necessarily chosen for the most optimal growing conditions (i.e., exposure to sunlight, soil quality, slope) but rather to use vacant or remaining available land. Compounding this, especially in the urban core of the AMB, which is characterised by post-industrial spaces and old housing stock, is the challenge of potential soil contamination or other environmental pollutants potentially impacting the safety of the food and growing conditions. Furthermore, in the semi-arid climate of the AMB, urban agriculture, if not planned properly, runs the risk of placing higher environmental pressure on water resources with rising temperatures and more frequent droughts.

Conclusion

The AMB is far away from being able to feed itself, and ultimately this would be an unrealistic goal given historical consequences of urbanisation and the current ecological limits of the landscape. However, there is momentum building in food policies in the AMB as well as in urban agricultural practices to cover more urban food demand with local production. Although urban agriculture will ultimately only be able to provide a small part of the total food demand of dense urban spaces, it offers the opportunity to diversify the scales of food production while delivering other benefits to the city. To what extent and through which urban agricultural practices are two questions that remain to be answered.

Comments (0)