Antonin Pépin is a PhD candidate at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRAE) and at the Technical Centre for Fruits and Vegetables (CTIFL). His research focuses on environmental assessment of French organic vegetable farms using the Life Cycle Assessment method. He has an agronomist background and has worked for an environmental NGO and for an organic waste treatment industry. You can reach Antonin at antonin.pepin@ctifl.fr.

Hayo van der Werf works at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRAE). His research focuses on the multicriteria assessment of the environmental impacts of agri-food systems. He mainly uses the life cycle assessment methodology and is most interested in assessing of organic agriculture production systems.

Image: Medium-sized market garden growing 5 ha for the local market, in Bouches-du-Rhône.

In food debates in France, we often hear that organic food products are more this or less that than conventional products – a framing that implies organic production is a homogenous whole. Another perspective suggests that there is a bifurcation between “real” organic producers who use agroecological principles, as opposed to “to-the-letter” producers who comply with organic regulations but do not follow the spirit of the overarching principles of organic farming, instead approaching farming in a so-called “conventionalised” style. Which framing accurately reflects the state of organic farming? We sought to answer this question through our research. This blog post is based on our paper Conventionalised vs. agroecological practices on organic vegetable farms: Investigating the influence of farm structure in a bifurcation perspective.

Is organic vegetable production monolithic?

Organic agriculture is characterised by the prohibition of synthetic chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Beyond these certified standards, the overall principles that support organic farming (OF) are the use of natural substances and a limited use of non-renewable resources and external inputs (EC, 2007). However, the hypothesis of “conventionalisation” of OF, defined as “the introduction of farming practices that undermine the principles of organic farming” (Darnhofer et al., 2010) suggests that the mainstreaming of OF may increase the reliance of certain organic farms on external inputs. OF based on applying a limited set of organic principles can be very different from OF based on agroecological principles (Gliessman, 2013). The “bifurcation hypothesis” is the idea that a chasm has grown between these two models, hereafter referred to as “agroecological” and “conventionalised” organic systems (Darnhofer et al., 2010).

Beyond academic discussions about the relevance of this hypothesis, the bifurcation of OF is a controversial topic in civil society. In France, the media reveal growing concerns about “two-speed” OF (Le Monde, 2017) and doubts of consumers about whether an organic label guarantees true sustainability. These concerns are related to the rapid growth of OF in the country.

In France, the bifurcation debate is increasing for organic vegetables, a sector that has grown strongly in recent years, fed by parallel contrasting trends. On the one hand, the strong increase in sales, particularly in supermarkets, may favour larger and more specialised farms and encourage large conventional vegetable farms to convert to OF. On the other hand, France has seen a recent and growing development of “microfarms”, created mainly by new entrants with no agricultural background and strong social and environmental aspirations, and characterised by small areas, diversified production, short supply chains and radically alternative practices (e.g. inspired by permaculture) (Morel and Leger, 2016).

A typology and a conceptual framework to analyse diversity

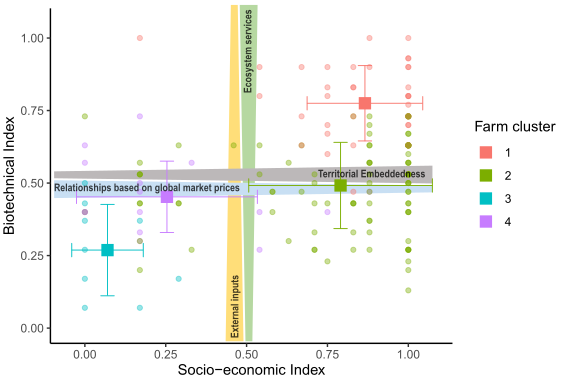

The bifurcation hypothesis suggests that organic vegetable farms are diverse. To analyse this diversity, we created a typology, based on a statistical analysis of various criteria (e.g., surface, labour, farming practices, marketing channels), and adapted an analytical framework (fig. 1) proposed by Therond et al. (2017). This framework characterises agricultural systems along two dimensions.

The first dimension corresponds to the biotechnical functioning of farming systems and assesses the "balance between external inputs versus ecosystem services". In our study, biotechnical functioning is therefore our proxy to quantify the extent to which OF is conventionalised or agroecological. Hereafter we call it “agroecological score”.

The second dimension corresponds to the socio-economic context of farming systems and assesses the balance between relationships based on global market prices vs. “territorial embeddedness”, defined by Thérond et al. (2017) as “social, spatial and ecological issues which mitigate purely economic relationships and behaviours centred on global market prices”.

To position the farms within this framework (fig. 1), we defined a quantified index for each dimension based on their practices, ranging from 0 (i.e. external-input-based system or system connected to the global market) to 1 (i.e. biodiversity-based system or system with high territorial embeddedness). The bottom left corner below therefore represents “conventionalised” organic farms, while the top right corner represents “agroecological” organic farms. A typology, though simplistic, helps in understanding the diversity. Based on an online survey of farmers from 165 French organic vegetable farms, we defined four types (clusters), described below. In each cluster below, we give statistics that are the median value for the corresponding farm cluster.

Fig. 1. Representation of the 165 farms sorted by four farm clusters on a framework defined by the socio-economic index and the biotechnical index (i.e. agroecological score). Darker circles indicate overlapping farms with the same values. Squares represent the mean of each index, whereas error bars represent the standard deviation of the two indexes for each farm cluster. (Therond et al., 2017)

Cluster 1: Microfarms for the local market

Fig. 2 - Microfarm (type 1) where 35 different vegetables are grown on 2500m², in Vaucluse. The straw controls weeds and enriches the soil with organic matter.

Cluster 1 farms had the smallest areas with an average of 0.5 ha of outdoor vegetables and 0.04 ha of sheltered vegetables. They also had less labour (1.3 full-time equivalent (FTE)) and fewer tractors (1.0 vs. 2.1), when compared to the median for all farms in the survey. With 30 vegetable types grown per farm, these farms were diversified, meeting Morel and Leger’s (2016) definition of a microfarm. Farmers placed high importance on dedicating space to biodiversity. They used external inputs less and practiced significantly more no-tillage than farms in other clusters. Weeds, pests and diseases were controlled mainly using natural practices and local resources such as crop rotation or covering the soil with straw. Some of the farms’ seeds and seedlings were self-produced. Most fertilisation was self- or locally produced, but the percentage did not differ significantly from that of the entire sample. Their annual revenue was low (most less than 30 000 €), and they had high territorial embeddedness, selling to the local market through short supply chains. Most farms (93%) had been organic since their creation, which was recent (median of five years), which may help explain the low annual revenue. Some of these farms may not have reached their full development. Most farmers declared that they practiced “alternative” farming, such as permaculture, which Morel and Leger (2016) consider to be a feature of microfarming.

Cluster 2: Medium-sized market gardens for the local market

Fig.3 - Diversified farm (type 2) growing 5 ha for the local market, in Bouches-du-Rhône. The tarpaulins avoid weeds on the row; the inter-rows weeds are left in flower at the end of the season to feed the pollinators.

Cluster 2 farms were larger than cluster 1 farms with 1.7 ha of outdoor vegetable area and 0.2 ha of sheltered vegetable area, but were smaller than the farms of clusters 3 and 4. More people worked on the farm (2.7 FTE) than on cluster 1 farms, but many fewer than on the farms of clusters 3 and 4. With 40 types of vegetables grown, these farms were highly diversified. Farming practices were mixed between agroecological-based practices and the use of external inputs. Most farmers declared that they practiced “non-alternative” farming. Most farms had been organic since their creation (84%), which was a period (median of 9 years) longer than that of cluster 1 farms but much shorter than those of cluster 3 and 4 farms (Table 1). With 99 farms, a wide range of annual revenue (€30-300k) and mixed practices, this cluster was the most heterogeneous.

Cluster 3: Producers specialised in cultivation under shelter (greenhouse, tunnel) for long food supply chains

Fig. 4 - Producer specialised in cultivation under shelter (type 3), on 2 ha for the national market, in Bouches-du-Rhône. The tarpaulins allow to avoid weeds on the row, purchased bumblebee hives allow to ensure pollination.

Cluster 3 farms were characterised by a large sheltered vegetable area (3 ha), which occupied ca. two-thirds of the utilised agricultural area. Labour (7 FTE) was higher than those of clusters 1 and 2. They were specialised, producing just a few types of vegetables (12) sold in long supply chains to national and export markets. Annual revenue ranged from €100-1000k. Almost all farms were located in the south-east of France, an area known for producing vegetables under shelter throughout the year for export. They used external inputs for seeds, fertilisation and pest management intensively, and biodiversity was not their main concern. These farms had a long history (30 years) and had all started in conventional farming before converting to organic.

Cluster 4: Large market gardens specialised in outdoor cultivation for long food supply chains

Fig. 5 - Producer specialised in outdoor cultivation (type 4) on 24 ha, in Ille-et-Vilaine. Weeding is done with a tractor before planting the crops (using the false seed bed technique, where weeds are allowed to germinate in a prepared seedbed and then are removed) as well as after planting.

Cluster 4 farms were characterised by a large outdoor vegetable area (14.5 ha) and a small sheltered vegetable area (0.07 ha). They had more workers (7 FTE), more tractors (5) and produced fewer vegetables (11) than farms in clusters 1 and 2. They ploughed significantly more than farms in other clusters. They used mainly local fertilisers, sometimes combined with purchased fertilisers. Annual revenue ranged from €100k to more than €1000k, and they sold in long supply chains to national and export markets. They started farming a median of 28 years ago, the majority of them in conventional farming before converting to organic (56%), and declared that they practiced “non-alternative” farming.

Link between some structural factors and bifurcation

Our results highlighted biotechnical and socio-economic heterogeneity among French organic vegetable farms. The diversity of farming systems can be interpreted as evidence of the coexistence of “agroecological” and “conventionalised” OF and as a sign of possible bifurcation. Since bifurcation is a dynamic process, confirming the “bifurcation hypothesis” would require further long-term study.

The smallest farms were more likely to implement agroecological practices, but the degree of agroecology is not directly determined by the size of farms. Not being the largest, farms specialised in cultivation under shelter are the most “conventionalised”, whereas farms of clusters 2 and 4 have a similar degree of agroecology, while having different size.

Our study showed no discontinuity on the biotechnical axis, which suggests that the dichotomy between “agroecological” and “conventionalised” organic farms should be considered instead as a spectrum, with two poles and a gradient of farms between them. The highest agroecological scores were associated with short supply chains, although high agroecological scores did occur with some long supply chains, which suggests that high agroecological scores in organic vegetable production can be reached with long supply chains and should be investigated further.

In the spirit of organic farming principles, the more agroecological the farming, the better. However, in our study we have not yet assessed whether higher agro-ecological scores result in better biodiversity on the farm and/or lower environmental impacts (e.g. lower carbon emissions).

Lastly, our study shows that the farms created as organic tend to be more agroecological than the farms converted from conventional farming. As farms created as organic in our sample were quite recently established, contrary to those that had converted from conventional farming, the comparison may be biased. For example, idealistic new entrants who start out with radical alternative practices may make conventionalisation trade-offs later.

In conclusion, we found that organic farming, in the French vegetable production context, is diverse in terms of both farming practices and commercial channels, and should not be considered as a homogeneous whole. This may be a sign of a bifurcation between “real” organic producers who use agroecological principles, as opposed to “to-the-letter” producers. However, there is no clear boundary between the two poles and most of the farmers partly use agroecological principles, to a variable extent.

Bibliography

Le Monde, 2017. Vers une agriculture bio « à deux vitesses ». Bolis, Angela. Le Monde 18/01/2017.

Darnhofer, I., Lindenthal, T., Bartel-Kratochvil, R., Zollitsch, W., 2010. Conventionalisation of organic farming practices: from structural criteria towards an assessment based on organic principles. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 30, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009011

EC, 2007. Council Regulation (EC) No. 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Regulation (EEC) No. 2092/91. L 189, on 20.7.2007.

Morel, K., Leger, F., 2016. A conceptual framework for alternative farmers’ strategic choices: the case of French organic market gardening microfarms. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 40, 466–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2016.1140695

Therond, O., Duru, M., Roger-Estrade, J., Richard, G., 2017. A new analytical framework of farming system and agriculture model diversities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 37, 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0429-7

Comments (0)