Transcript for Ep2. A complicated relationship with meat

Matthew Kessler 0:04

When you see a piece of steak on a plate or a big pot of chicken soup, what are your first thoughts? Do you see a healthy, nutritious meal, a piece of animal flesh, a comfort food from childhood, or something else?

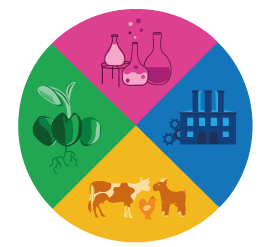

Thanks for tuning in again to Meat the Four Futures. I’m Matthew Kessler, your guide for this podcast series, where we explore four possible futures for meat and livestock: an efficient meat future.

Jayson Lusk 0:34

We know people like to eat meat. How can we give them what they want while reducing the impacts that that consumption has on the environment, and one way to do that is to increase efficiency.

Matthew 0:45

An alternative-meat future.

Isha Datar 0:47

To hear that we can grow meat from cells made me feel like oh my gosh, this is such an obvious next step for humanity; and a real win-win-win, when you think about not just reducing environmental impact, but also animals need not suffer anymore for food.

Matthew 1:05

A less meat future.

Tristram Stuart 1:07

We can use food and farming to sequester carbon in soils, to create habitats, rather than destroying them. My cows are bringing in nutrition from part of the landscape that I cannot otherwise make a part of my food system.

Matthew 1:21

And a no-meat plant based future.

Jan Dutkiewicz 1:23

We're really thinking about how to make a more sustainable and just food system, from the perspective of animal ethics, public health ethics and environmental ethics.

Matthew 1:33

Debating the future of meat and livestock is really tricky. Because our views on meat could be formed by our cultures, our values and where we live in the world. So what does a good future for meat look like – well that’s going to mean something different for everyone.

In this episode we head to India and Burkina Faso to hear two different solutions to meet the surging demand for meat across the global South. We talk about the ethics of eating animals in the West, where we’re often distant and detached from where meat comes from. But first we’re going back in time, to look at the role that meat has played in our evolutionary diet.

Part 1: Meat matters – past and present diets

Frédéric 2:32

Well, it's indeed often said that meat is the food that made us human. But it's certainly not the only factor, let's be clear.

Matthew 2:41

Frederic Leroy, is a food scientist and technologist. And a professor at Brussels University in Belgium, with a particular expertise and interest in animal source foods. Meat has indisputably been a part of our diets dating back to pre-historic times.

Frédéric 2:57

I think we have to see this as a combined biological and social process that was triggered when our ancestral lines started to deviate from the other apes when we entered the new ecosystem.

Matthew 3:11

The ancestors of humans migrated to grasslands and semi-dry woodlands and added meat and fats to their diet.

Frédéric 3:19

So there's a dietary shift towards more nutrient dense foods. But at the same time, this new ecosystem also forced us into a new social behavior and a new social system.

Matthew 3:33

These hunter-gatherer societies had more social cooperation, which required bigger brains.

Frédéric 3:38

Because it has to do with understanding the other. It comes with aspects of altruism. So there’s a demand for intelligence and bigger brains, and at the same time, we’re switching to new diets with higher nutrient density.

Matthew 3:52

This is an intertwined process – you need to grow the brain and you need the building blocks to maintain that growth – which was possible when eating meat.

Frédéric 4:02

Now, of course, a lion also eats lots of meat and doesn’t necessarily increase brain size. The evolutionary trigger there is probably the social aspect. If we talk about the social developments that meat was at the very center of ancestral cosmologies, and rituals, and the way people organized society. Hunt, and even the eating of meat, or the killing of the animal had a very significant place. This is something that is still underneath the surface and plays its role.

Matthew 4:32

So meat played an important role in our evolutionary diet – but does that matter?

Frédéric 4:37

It's a great point, of course. And there's no fundamental reason why we should keep with evolutionary foods just for the mere fact that this was the case in the past. However, it seems to be the case that humans are the only species where we assume that we could deviate from our evolutionary diets.

Matthew 4:56

Not eating the same diet as our ancestors also applies to the animals that humans have domesticated over the last 10,000 years, like pets, companion animals and livestock.

Humans are pretty adaptable with their diets - and some say that’s part of our evolutionary strength. But at the same time, we also know that our bodies are adapted to eating meat.

Frédéric 5:18

We know that diets are complex, we know that human health is complex. And that matching those two aspects is not something straightforward.

Matthew 5:30

Frederic Leroy is a strong defender of this evolutionary diet. For starters, meat is packed with nutrition.

Frédéric 5:38

The problem we often have today is that we tend to think that if we just supplement a couple of missing nutrients, we're matching the nutrient spectrum. It's a bit as if you will eat cornflakes that is fortified with all sorts of vitamins, and that will be your proper meal. A dietary matrix is complex, and the matrix effects are not to be underestimated.

Meat is of course high in protein, and the protein is extremely bioavailable. If you compare it with cereals, that's a very big difference. If you compare it with pulses, the difference is somewhat less, but it's still significant.

Matthew 6:13

Meat and other animal products contain all the amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, that we need. But you can also get all these amino acids through a combination of different plants, like beans and grains.

Protein deficiencies aren’t the usual problem with vegetarian and vegan diets, but getting some of the other nutrients can be pretty tricky. .

Frédéric 6:36

Then you have a range of minerals: iron, where heme iron is of course preferentially absorbed compared to ionic forms. Zinc, selenium. There is a spectrum of nutrients there that are easily obtained through meat and are harder to obtain with plant sources.

It's not something I'm here advocating for, but it's interesting to see that people can apparently do well on diets that constitute only of meats. It's a very solid source of dietary adequacy.

The evaluation you could make here is that you can, in principle, take out meat from the diet. And we know that this is possible because people do that and remain healthy. But it just complicates things. Especially for vulnerable populations.

Infants and young children or even adolescents, young women, pregnant or lactating women, elderly, specifically as well, problems of sarcopenia. Those vulnerable populations have higher needs. And those higher needs are not easy to match with plants only.

The more you become restrictive. The more you throw out certain food categories, the more difficult it becomes.

Matthew 7:51

Clearly, meat packs a nutrient punch. But it’s been contested for lots of other reasons. Some environmentalists and ethicists have raised concerns in modern times. But objections to eating meat go back much further back in history. For example, people from different regions and ethnicities across India, China, Japan, and Ancient Greece, have historically objected to eating meat for reasons related to health and spirituality.

Frédéric 8:18

Typically, in the past, that was very much connected to religious ideas, ideas of purity, ascetic ideals, where meat was seen as something that is very worldly, very sensual, as well, you know, it's a red food. It bleeds. If you are able to avoid eating meat, it means that you're pure enough to be among the spiritual realms. Even you know the fact that the Garden of Eden diet was basically a plant based diet.

Matthew 8:55

Frédéric Leroy focuses on the growth of one particular movement in the western world that he sees as having a big influence on current debates.

He traces back an anti-meat bias to over 100 years ago to organizations that were promoting vegetarianism, especially in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Frédéric 9:15

In the 19th century, certain religious movements, including the Bible Christians, a bit later, the Seventh Day Adventists, or Puritan movements that were again very spiritual - they came up with a philosophy that meat should be avoided. They were framing it as a sinful behavior.

Matthew 9:38

Now we fast forward to the progressive era, which was around 1890-1920 in the United States.

Frédéric 9:45

And during the Progressive Era, being a vegetarian was connected to all sorts of ideas that were seen as world changing. And very noble ideas. We’re talking about anti-slavery, women rights.

Matthew 9:59

Frederic Leroy points out that it was a very specific group that was leading this movement.

Frédéric 10:04

Progressive, urban, very much Anglo Saxon, middle or upper classes. And at the same time, there was a development also where vegetarianism was connected to the health discourse. And that was triggered by people like Sylvester Graham, but also Kellogg, John Kellogg.

Matthew 10:24

Sylvester Graham, best known today for his invention of Graham crackers, was an American Presbyterian minister who was convinced that humans were physiologically similar to orangutans and should therefore stick to a quote “natural meat free diet.” And John Kellogg, the guy behind Kellogg’s corn flakes, was a Seventh Day Adventist.

Frédéric 10:45

So he started from the idea that meat is sinful, and that it leads to sinful behavior such as sexual activity and masturbation and it had to be avoided and specifically, children had to stay away from red meat. But Kellogg was also very much interested in medicine. Because of that he developed a very influential movement that was putting emphasis on lifestyle, pure vegetarianism, and all sorts of other things. And both Graham and Kellogg, and people from the vegetarian societies, started to publish articles in scientific journals or journals that have a scientific appeal, and it entered health discourse - became connected to better health, in the minds of the upper classes, and the progressive upper classes in particular.

Matthew 11:36

Frederic Leroy also points to the field of dietetic studies - that looks at how what we eat affects our health. Throughout the 1900s, studies focused more on individual consumption, and didn’t always separate the social, economic and environmental factors that shape health outcomes.

Frederic 11:53

So you have an association there that is created. And it is an association that is, in my opinion, still responsible today for what we consider to be the healthy user bias.

Matthew 12:04

The healthy user bias is a problem in health studies that arises when the study is performed on a population that is not representative of the general public.

Frédéric 12:14

Now, if you look at upper middle classes that do not eat much meat, they come out as more healthy, because they're also - of course, having access to better health care, they smoke less, they drink less, and so on. So they’re healthy, rich people, and they tend to eat less meat.

Matthew 12:30

So some of the health advantages with plant-forward diets could be a result of vegans and vegetarians making other choices that are better for their health.

Studies about diet and diseases are notoriously complex. Researchers are using the best available science and methods to look at associations and control for confounding factors - like exercise, smoking, access to health care.

Most studies and health organizations conclude that we need to eat less meat than we do today in high meat consuming countries. Frederic Leroy questions the studies that conclude we should eat zero red meat and points to the role of meat in our evolutionary diets.

Frédéric 13:17

And because of those nutritional studies, you get a kind of feedback mechanism that says, “Look, science is showing here that meat is not good for you.” Which is a very bizarre thing. If you think about the amount of meat that is being eaten by certain populations on Earth, especially in the ancestral populations.

Matthew 13:33

How the meat is produced today, the environments we eat it in, and how much we eat is very different than the past. For starters, we eat a lot more processed meat - meat that is flavored or preserved with additives.

And on the whole, in rich countries with western diets, we do eat a lot more meat today and most health recommendations, based on the latest science, is to reduce meat consumption. But what is too much?

In the United Kingdom for example, the nutritional recommendations are to not eat more than 70 grams of red or processed meat a day. People were eating over 100 grams 15 years ago, but that has been steadily declining.

A really important question here is - if people cut down on how much meat they eat, what are they eating instead? Is it whole foods like beans, peas and lentils, or is it something else?

Frederic Leroy worries about the calls to remove or limit the production and consumption of animal sourced foods, and is afraid that it has become a scapegoat for the more processed foods accompanying western diets.

Frédéric 14:45

And that's really the elephant in the room. We very clearly see that whenever non-western populations are adopting the Western diet, that problems start to occur. We've seen it, for instance, with Siberian nomads, who were perfectly healthy, and then they start to eat processed noodles, and all sorts of other very refined products. And they immediately develop the symptoms of the metabolic syndrome. So there's something about the Western diet that is intrinsically unhealthy.

It's all those very refined products that are high in sugars, combine those sugars with refined starches, combine them with oil. Often, salt thrown in just to enhance the taste and enhance the stability. And that cocktail seems to be something very detrimental.

And now you have a situation today, where mostly urban middle-upper classes are looking at meat as something that is toxic. And behavior that is either egoistic or harmful for the planet and harmful for the animals. So there's a very huge contrast here, between the way that people looked at meat in the past, and the way that people look at meat today. At least some people because if we're talking about certain Western populations, we shouldn't of course generalize this to the entire planet. If you go to the global South, you get a very different response.

Matthew 16:08

That’s Frederic Leroy, food scientist and professor at Brussels University in Belgium; and a strong advocate for meat and other animal sourced foods as good, nutritious food for humans; from millions of years ago, up until now.

Next we’ll visit Burkina Faso and see how people eat, farm and relate to livestock differently.

Part 2: Meat, as a livelihood and a bank

Matthew 16:47

Meat and livestock take on many different meanings across the world. It’s important to people’s livelihoods. It’s connected with different religious, spiritual and cultural practices. And it is also a status symbol.

Vinsoun Millogo 16:59

When we have poultry, you are better than someone who has no animals.

Matthew 17:06

Vinsoun Millogo, researcher at Nazi Boni University in Burkina Faso, talks about the cultural status of having animals. The more animals, the higher the status.

Vinsoun 17:16

When we have a goat, then you improve a little bit. When we have goats and sheep, then you get a degree. Now when you have poultry, goat, sheep, and cattle, then you get your PhD. Which means: you are a big guy.

Matthew 17:37

Burkina Faso is a country in the center of West Africa with around 20 million people.

In Burkina, there are a few types of livestock production, including a more traditional system, which is still, after around 2000 years, widely practiced today.

In this traditional system, animals are moving with people across the land. Before colonization, pastoralists used to travel 100s of kilometers before the country borders of today existed.

Vinsoun 18:04

We have a big area where you can move everywhere. And we call that: nomadism system.

Matthew 18:11

Nomadism or pastoralism, is still a way of life by tens of millions of people today, mostly across Asia and West Africa. There are also thousands of Sami people herding reindeer across northern Scandinavia. Nomadism is a system that has almost no inputs and relies on landscape level grazing systems where animals follow their food. This traditional system makes up over 95% of livestock production in Burkina Faso. More modern livestock systems, that improve animal productivity and efficiency with different feeds, technology and infrastructure, make up only 1% of production.

So that’s production, how about consumption? In Burkina Faso, a little over 12 kg of meat is consumed per person each year. Compare that with 66 kg per person in Sweden, 80 kg in the UK, and 125 kg (or 275 pounds) in the US.

Many people in Burkina want to eat more meat; but not all can afford it. So part of your diet depends on your income, but it also matters if you’re living in a city or a village.

Vinsoun 19:36

In rural areas, people have different views regarding meat and milk. It depends on your culture.

Matthew 19:45

Some tribes don’t eat meat or milk at all because of their traditions. And in many cases in rural areas, it’s only eaten on certain occasions.

Vinsoun 19:54

If there is a marriage, if they have some special celebration, they will slaughter a goat, sheep or beef cattle. Then, you can eat meat that day.

Matthew 20:06

Having animals in Burkina Faso is a lot of like having financial security - like a bank. You know that there is a market for them and that they will sell.

Vinsoun 20:15

People want to keep animals because it's a very secure system in the rural area, even today. You know we also grow cotton, the money they get from cotton they put into the animals.

If I invest in animals, anytime I have money. This is very, very, very important. I think it's one of the big strategies of fighting against poverty in rural areas in West Africa.

Matthew 20:47

Vinsoun Millogo sees a big opportunity to develop the livestock sector in Burkina Faso, but there are many challenges. There’s climate change, there’s competing for land with other industries like mining, and there are some big knowledge gaps that he, as a researcher, is hoping to fill.

So while there is a growing demand for meat, the supply isn’t there yet within the country or the region. Vinsoun’s vision for the future includes West Africa producing a lot more of its own meat and adopting more modern practices. West Africa already has over 400 million people, and the population is expected to double in the coming decades.

Vinsoun 21:29

And Africa will be 2 billion and half. Who will feed if we are not working on a strategy to get more meat? Anyway, we need meat. It’s a very big challenge. Fortunately, we are thinking right now. Otherwise, I'm really worried.

Matthew 21:4

Vinsoun Millogo at Nazi Boni University in Burkina Faso. But where we’re heading next, there are also other solutions to meet the rising demand for protein – a solution without more livestock.

Part 3 - The future of alternative meat in India

Matthew 22:17

I don’t think I ever asked you, do you eat meat?

Nicole Rocque 22:20

No, I don't. I've been vegetarian for about three years now.

Matthew 22:26

Nicole Rocque, senior innovation specialist at the Good Food Institute India,

Nicole 22:31

I grew up eating meat. I’ve been trying to go vegan, but getting rid of dairy in an Indian household is actually quite difficult!

Matthew 22:41

Nicole Rocque talks about the unique set of challenges that the country faces.

Nicole 22:46

At the start of this year, India overtook China to become the world's most populous nation with 1.5 billion people. And of major concern is the ability of the nation to feed this fast growing population without breaking the planet.

Matthew 23:03

By 2050, it’s estimated that one of every six humans on this planet will be living in India; where over 50% of the population rely on agriculture as a source of income. It’s a country highly vulnerable to climate change, and health challenges have worsened following COVID -19 and inflation. And given the size of this country, it’s a complicated picture!

Nicole 23:29

When we're talking about feeding India, we're also talking about feeding many different Indias. So while on the one hand, you are seeing a rapidly growing population with increasing disposable income and upward social mobility, that is starting to eat more meat and driving the demand for its production globally. On the other hand, we still have a majority of the population that is not consuming nearly enough protein, and performing poorly on a wide range of nutritional indicators.

Matthew 24:06

The many Indias contain multiple stories. On one hand it has the most vegetarians in the world, with 30% of the population doesn’t consume meat, but many do eat dairy products - like dahi, paneer, and ghee.

The rest of the Indian population eats some meat, though it’s a fraction of what’s eaten in Europe and the Americas. While some people aren’t eating for religious reasons, the biggest factor that limits meat consumption is people’s income, which as we said, is expected to rise.

Nicole 24:38

In order to halt a climate catastrophe, we need to immediately cut methane emissions, halt deforestation, prevent agricultural sprawl, and shift consumptions towards plant forward diets.

Matthew 24:55

So instead of meeting the existing and growing protein demand with more animal production, the Good Food Institute-India is building out the ecosystem for alternative proteins to thrive.

Nicole 25:07

Asking people to eat chickpeas and not chicken has never really worked. In fact, global meat consumption is predicted to go up. So our theory of change with these alternatives is quite straightforward. It's to give people what they want, but made in a vastly different way that safeguards the planet and public health.

Matthew 25:30

They are working with entrepreneurs, investors and the corporate food sector across the value chain to help to develop these products and bring them to markets.

Nicole 25:40

India has tremendous crop biodiversity with crops like pulses, millets and hemp, offering huge promise to diversify raw materials for the entire smart protein sector globally.

We see huge potential to build a globally competitive manufacturing supply chain for the sector out of India, by which we hope alternative proteins could become widely and cheaply available.

Matthew 25:22

That was Nicole Rocque of the Good Food Institute India, who we’ll hear from again in the upcoming alternative meat episode.

So how will this rising demand for meat be met across Africa and Asia and as populations grow and incomes rise? How will the cultural significance of livestock be kept? Will alternative protein products play a small role or big role? And will more intensified farming systems that the west has modeled take over to meet the demand?

Our last stop is in the United Kingdom where we hear a cautionary tale about the consequences of having a society so removed from animal farming.

Part 4: The meat paradox of the Western world – wanting to eat meat, but not wanting to know

Rob Percival 27:05

As humans we have been consuming animals for at least 2 million years. And for most of that history, it appears that we were much like any other creature, we were like a fox or a lion or a bear. We just ate the foods that were available to us. And if they were nourishing, then they were good.

Matthew 27:20

Rob Percival is head of food policy for the Soil Association in the UK and author of the book “The Meat Paradox.”

Today we slaughter over 80 billion land animals for food each year. That includes more than 70 billion chickens, which is followed by pigs, sheep, and cows.

So while meat has been an important part of our evolutionary diet, our relationship with meat is very different today.

Rob 27:49

Well, the last few years, I've been deeply embroiled in this polarized meat debate that's sort of spilled across society. And I began to be intrigued by the emotional complexity of the debate.

That emotional complexity was brought into view, in part by a visit to an abattoir, where I spent the day closely engaged with the process of slaughter, in a sort of, a few intimate moments with the animals as they pass through.

And from that point, I went to investigate this new and emerging body of psychological science, which tells us some really interesting and surprising things about how we relate to animals.

Matthew 28:29

In 2011, two psychologists coined the term the meat paradox, which explores how we are able to hold two conflicting beliefs at the same time.

Rob 28:39

We care about animals, but we often treat farmed animals very badly, so there's a gap between our values and our behavior.

And in the past decade, researchers have probed the sort of cognitive and cultural mechanisms underpinning this divergence. And that's been published under the banner of the meat paradox.

Matthew 28:57

What does a gap between our values and behavior look like in practice?

Rob 29:01

Most people in Britain say that they care about animal welfare, but it's intensively farmed poultry and pork, which are associated with routine welfare failings, which make up the bulk of the meat in our diets.

One in three of us also say that we're eating less meat, we say that we're going veggie or vegan or flexitarian. But that reduction isn't reflected in sales or supply data. So it seems that we say one thing and do another.

Matthew 29:26

It’s actually pretty common that we misreport our eating choices when it comes to meat. There are studies across the US, Europe and the UK that suggest eating less meat is aspirational, but it’s not routinely reflected in people’s diets. This might say something about people’s strategies to either avoid or disassociate with where meat comes from.

But is this meat paradox new? Is it a social invention of modern agriculture, or does it have a deeper history?

Rob 30:03

So certainly, the industrialization of agriculture in the past half century has posed novel concerns. But if you look across societies across human history, eating animals is always complicated. It's always ethically complicated. It's only allowed to take place in a sort of ritualized manner. If you look at pre-industrial societies, non-industrial societies, early agricultural societies, for example, the killing of animals had to be conducted by a priest. Temples were also open air butcher's shops, and the only meat that could be eaten was the sort of by-product of a sacrifice to the gods. And if you look in various indigenous hunting societies, there's a complex web of rituals and narrative which surrounds the kill, dictate how the body should be treated, the meat prepared, and so on. There's a story that's told about, in many cases, about the rebirth of the animal's soul. If that proper ritual procedure is followed. So it's always, always, embedded in a ritual context.

Matthew 31:04

Remember when Frederic Leroy was talking about the role of meat in our evolutionary diet. Well, he and Rob Percival are essentially describing the same thing. Hunting and eating meat was a really important social activity. But there was a big variation in how much meat our ancestors ate, from most of our diet, to a very small portion of it.

While Frederic emphasizes that eating meat is natural to our biology, Rob sees our loss of ritual and relationship with farmed animals as central to issues with meat consumption today.

Rob 31:35

In our society, we're kind of unique in that we've lost some of that. Instead of telling stories that help us make sense of what it means to kill animals, we simply look away. We avert our gaze. We find so many ways of distancing ourselves from that disturbing and potentially troubling fact.

Matthew 31:53

So Rob is presenting these three facts:

1) We eat more meat now than at any other point in history.

2) That supply relies on an industrial animal production system that is cruel to animals.

And 3) We deal with this by turning a blind eye.

But looking away is only part of the puzzle. There’s other factors, like how meat is now cheaper and more widely available than at any time in the past.

And there’s five large meat companies - JBS, Tyson Foods, Cargill, Chinese WH Group, and BRF - that together have an outsized influence on the production, distribution, and marketing of meat across the world.

On top accessibility and affordability, Rob points out that increased meat consumption has a lot to do with entrenched social norms.

Rob 32:44

These mechanisms of detachment and dissociation, fuel our consumption in an important way, where we feel fairly uninhibited when eating meat, typically. And this is certainly one of the factors which leads to the dietary patterns that we see in Western nations today.

Matthew 33:07

So, at the core of the meat paradox lies the fact that we as consumers are typically quite distant from the production of meat.

Rob 33:14

And often there's a degree of ignorance about the realities of food production, and particularly the processing of animal bodies. But what's really interesting is the psychologists are starting to discover that there's a high degree of willful ignorance that sits there as well. Most people, when quizzed, will explicitly say that they don't want to know about the realities of meat production, because they recognize that could make it more emotionally difficult to consume meat.

Matthew 33:46

Some research shows that how we see the world is actually shaped by our behavior. So rather than us understanding the world in a certain way and then acting on what we believe - they find the opposite can be true.

For example, for those who eat more meat, they actually imagine the animals they eat living in very good conditions; and for those who eat less, they have a, well, more realistic view of industrial animal production.

Rob 34:12

Among those of us who say that animal welfare is a high priority. A good chunk of us, around 50%, say that we don't like to think about animal welfare when we're purchasing meat, or animal foods in shops and restaurants.

So there's a deliberate degree of detachment there. And linked to this is a process of dissociation where we divorce our perception of the meat in our plate from the animal that provided it. So we can easily eat our way through a chicken sandwich, bacon sandwich or a hamburger without once thinking about the animal whose life provided it.

Matthew 34:45

Rob says that there are specific cognitive mechanisms that enable this detachment.

Rob 34:50

And that dissociation is shaped by how processed the product is; by the language we use to describe it; by the context in which it's purchased. It all creates this sort of bubble. And within this bubble, we divorce our behavior from our values, so that we continue to identify as animal lovers, as ethical consumers; whereas the behavior that we're exhibiting is actually quite divorced from that identity.

Matthew 35:18

To be clear, Rob Percival is not all-or-nothing on this issue. I asked Rob to share what he finds to be the most compelling argument to eat meat?

Rob 35:26

There are lots of good reasons to consume animal foods. They need to be balanced against the counter arguments. Some of the most sustainable farming involves animals, and those farmers need supporting. They need to make a sale. That's the world that we're currently living in. And there's a nutritional case for, in particular for some population groups. If you have young children, or if you're an older person, there are pretty good reasons to think that eating animal foods are going to be beneficial for you. Lots of us, especially healthy adults can subsist on a plant-based diet or a diet with little meat.

Matthew 36:01

And what is Rob’s argument to not meat?

Rob 36:04

There's an environmental reason for at least eating much less. In terms of eating no meat, I think the case is more ethical. For some people, it's just more clear to draw a boundary around the whole activity and say that there's too much going wrong with animal production at the moment, the way that we do it. There's too much harm involved, both to the animals and to the environment. And I just want to remove myself from those processes, from those systems. And one obvious way to do that is to adopt a plant based diet.

Matthew 36:37

Rob is not a stranger to discussing these topics and he hasn’t shied away from engaging with people who sit on all sides of this debate.

Rob 36:46

There's a really critical role for instincts and values in shaping the debate. So people's views on these subjects are only partly rational. They're rooted more in perceptions about the way the world works. You know, to what degree is behavior change possible or desirable? Do policymakers have the will or capacity to act? Can we trust novel technologies? How fast will those technologies scale? How should humans relate to nature? What are the ethical red lines? These are the sort of key questions that come each with an emotional charge attached to them. And they're difficult to grasp in a purely rational context. It's coming down to a sort of more guttural view of how people see the world, their vision of how everything works. And once you understand that people are coming from these very different paradigms. It becomes easier to navigate the debate and find that common ground and be able to talk in a sort of shared language.

Matthew 37:51

That’s essentially what we’re trying to do in this series. To hear people’s full views, a mixture of their values and their evidence-based arguments that they’re making for each of these four futures. So we can develop a shared language and have more constructive conversations.

Rob 38:10

I look forward to hearing the whole thing cheers.

Matthew 38:21

I find one of the hardest parts of navigating this debate, is the very fact that people want to put the spotlight on different parts of it.

Some care more about health and nutrition; others about reducing hunger; others greenhouse gas emissions or biodiversity loss.

Our starting points for these conversations about meat matters. Just think of how Frederic Leroy in Belgium and Nicole Rocque in India think about meat’s value and its impacts in completely different ways.

The future of food in general, and meat in particular, is a big topic with profound implications. There’s many stakeholders invested in different outcomes, and we’ve got a huge amount of evidence to digest.

Next week we begin our journey into the four futures.

First up: efficient meat 2.0.

Jayson Lusk 39:15

Number one, consumers in many parts of the world like to eat meat, it’s something they enjoy having in their diet.

Lars Appelqvist 39:21

We are part of the problem today.

Jayson Lusk 39:24

Talking to them about the environmental consequences or even animal welfare consequences doesn’t seem to have a big impact.

Lars Appelqvist 39:32

But we can see that, with the right steps, we can actually be part of the solution also.

Jayson Lusk 39:39

How are we going to produce enough calories and protein to meet a growing world population? And one way to do that is to try and increase efficiency.

Matthew 39:53

Thanks to you for listening – and please spread the word about us! It really helps if you rate and review us wherever you listen to podcasts.

And as we’re going to feature listeners’ comments in a later episode, please let us know what you agree and disagree with - and why. Record yourself in a quiet room and send it by the end of May 2023 to podcast@tabledebates.org.

And there’s more to Meat the four futures than this podcast. On our website, tabledebates.org/meat you can subscribe to our newsletter, try out our values-based quiz, and find links to resources mentioned in the episode.

This is a Formas funded project initiated by the Future Food Platform at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and produced by TABLE - a collaboration between the University of Oxford, SLU and Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

This episode was edited by me, Matthew Kessler and Ylva Carlqvist Warnborg, and a big thanks to the TABLE team. Music by blue dot sessions and epidemic sound.

Talk to you next week.